New York is the global headquarters of the art market, with the highest market share by value of art sales in the world. It is also a center of high net worth wealth, has the largest population of millionaires and billionaires globally, as well as being the key financial hub of the US. In 2019, the US accounted for 44% of sales by value in the global art market, having held a premium position in terms of the value for most of the last 50 years. New York is estimated to account for up to 90% of those sales, making it the epicenter of the market in 2020. Although China and other more emerging markets have developed at a rapid pace in terms of both wealth and sales of art, despite some reduction in its margin, New York remains unlikely to decline from the ranks as the leading global international art hub.

New York’s strength as a global art capital has been based around three fundamental areas:

The strong base of wealth within New York and the US. The US has by far the largest number of high net worth (HNW) and ultra-high net worth (UHNW) individuals in the world, as well as a stronger and more developed upper middle-class than emerging regions, which gives depth and scope to the development of the market at different levels. New York City is not only home to the most millionaires and billionaires of any city in the world, but it is also the temporary residence of many global millionaires. In addition, New York attracts a global audience of wealthy collectors and vendors to the art sales hosted in the city, as a critical mass of the world’s greatest art is exhibited and sold at museums, galleries, fairs and auctions there.

New York also has a highly developed cultural infrastructure, which is critical to supporting a healthy trade in art. Apart from being home to leading galleries and auction houses, New York has a dense and diverse range of public and private arts institutions, along with a wide range of specialized ancillary services for collectors and the art trade, including art insurance, banking, logistics and others. These services are supported by a network of experts, who also work independently throughout the New York art market in areas such as art advisory, appraisal, conservation, restoration and other specialties. The city is also a regular host to leading art fairs, exhibitions and other events, supported by a locally active community and diverse array of international visitors.

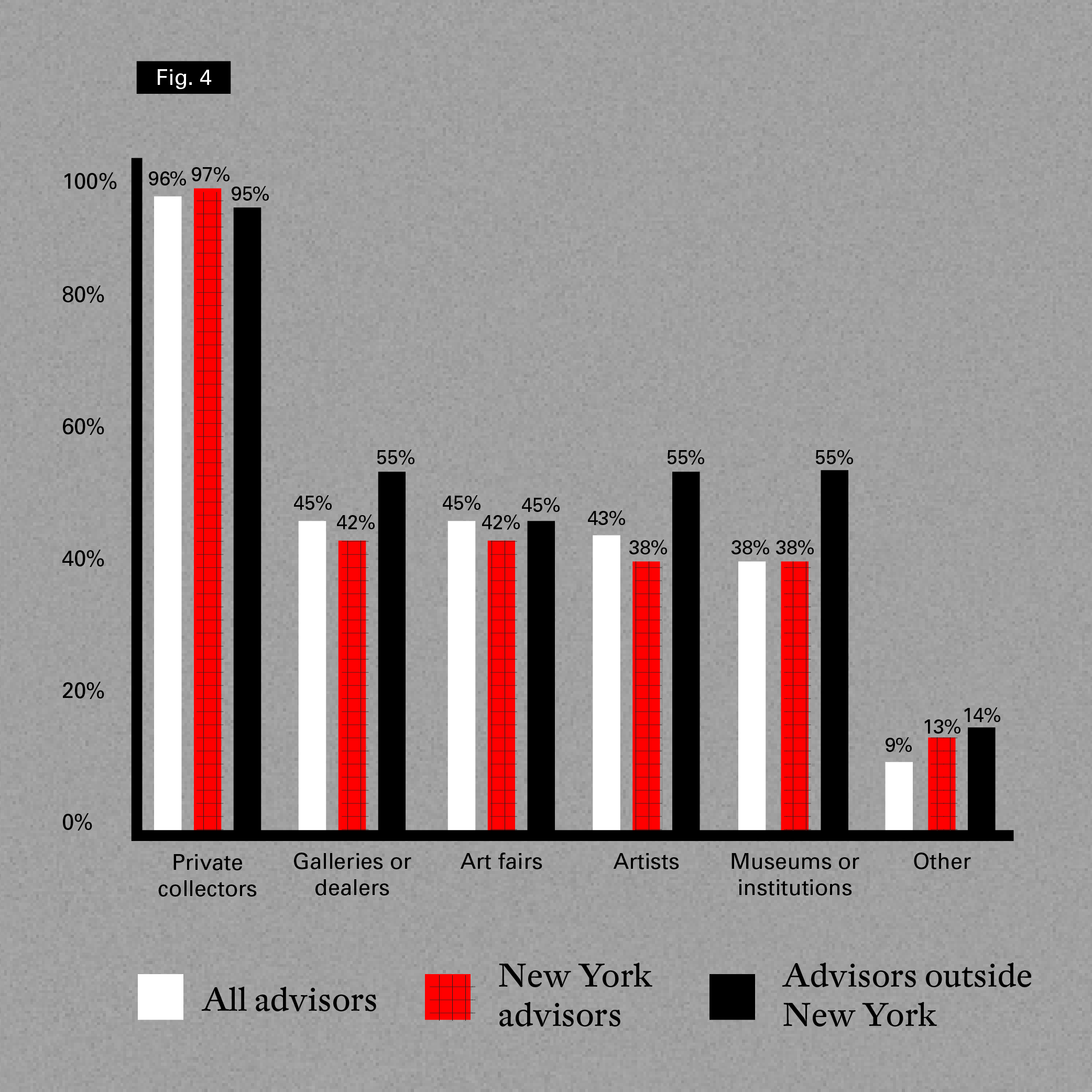

Finally, it is one of the most transparent centers worldwide for the art trade. The fiscal systems, the rule of law and the US Uniform Commercial Codes offer a high level of protection to local and international buyers and sellers, while giving businesses sufficient incentives to encourage inward and outward trade. Compared to many other nations, the US has a relatively business friendly fiscal environment and liberal trading regime which has been key in ensuring that some of the highest priced works of art in the world are sold in New York.

While these key strengths have solidified its leading position over many years, New York has faced some of its biggest ever challenges in 2020, many of which have had specific and acute effects on the art market. The COVID-19 pandemic forced the temporary closure of most galleries, auction houses, institutions and events, as well as leading to an exodus of many wealthy collectors from the city. The steady flow of international and domestic visitors, which totaled close to 67 million in 2019, has also been slowed significantly1. New York was not only one of the most severely affected cities in the US by COVID-19, but the crisis came on top of pressure already building in the city as art businesses, artists and others struggled with the rising costs of operating there. At this difficult point, this study aims to provide a descriptive picture of the New York art market, showing how it may be best placed to deal with the current challenges it faces. The report presents the findings of research carried out in 2020 on established New York collectors and their interactions in the market, as well as a survey of art advisors, who form a part of the critical network of art market expertise in New York. It reviews the strengths of New York’s collecting base, art market, cultural infrastructure and regulatory frameworks, all of which will be crucial to the speed of its recovery from the current crisis.

New York is the global epicenter of the art market

New York is a leading host city for global art fairs

New York is a key center for the art trade, artists and artists’ estates

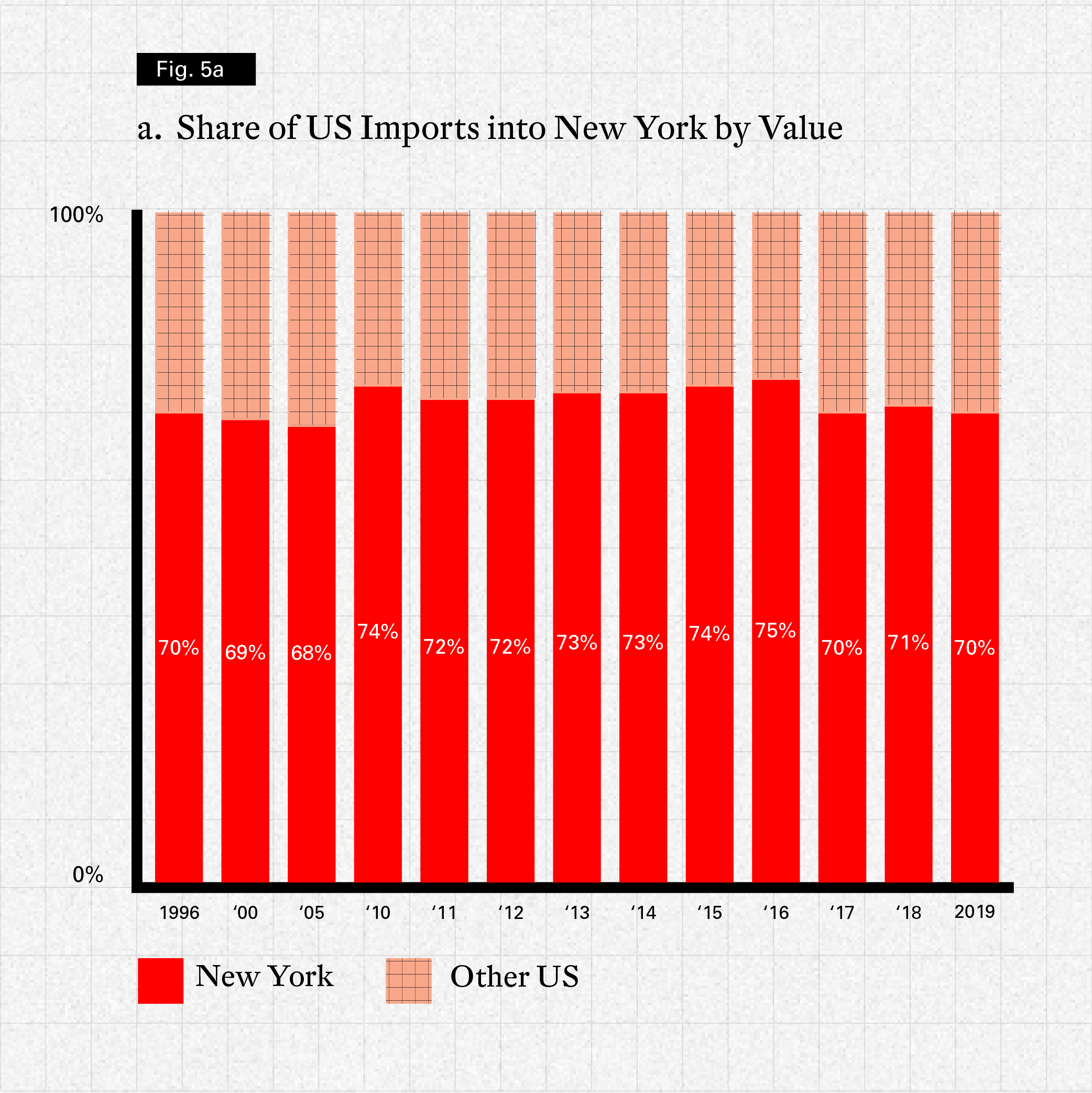

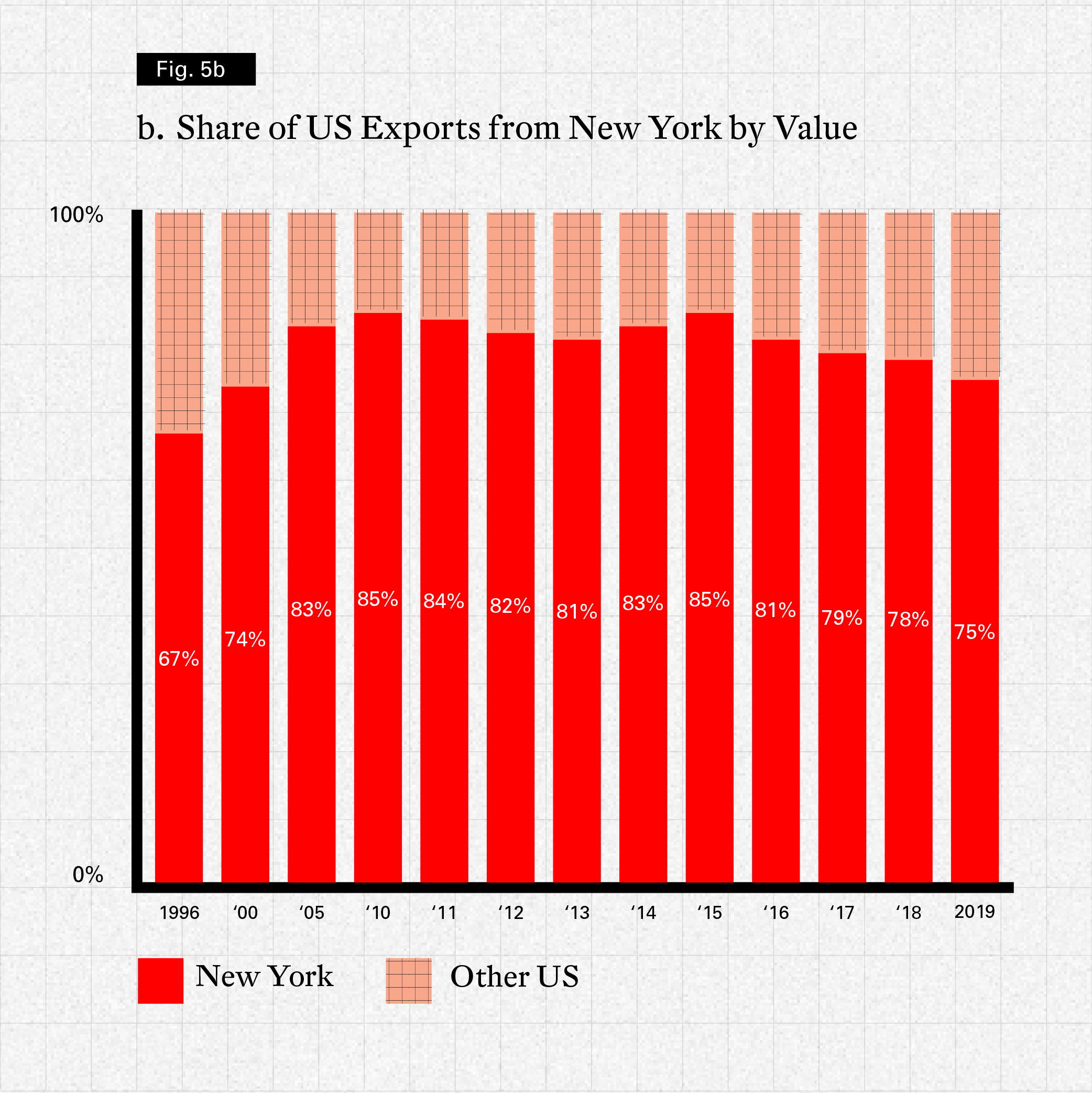

The bulk of the US cross-border trade in art enters and exits via New York

New York collectors have some of the world’s largest collections

New York collectors are significantly less investment driven than their global peers

New York collectors spend an average of $759,000 per annum on art

80% of the works in New York collections are by living artists

84% of New York collectors most often buy art at prices less than $50,000

The majority of the works in the collections of New York’s millennials are by emerging artists

Galleries are the most used channel to purchase art by New York collectors

26% of New York collectors have never made a purchase online

Over half of New York collectors prefer working with New York-based galleries

60% of advisors’ purchases or sales through galleries are New York-based

74% of advisors prefer to work with New York-based galleries

Advisors based outside New York make an average of 10 business trips to the city each year

New York-based advisors advise on sales or purchases of art worth $33 million per annum

New York collectors are highly engaged with gallery exhibitions and events

74% of advisors use art fairs often or always to purchase art

New York-based advisors prefer New York-based fairs to source and purchase art

76% of New York collectors are willing to attend events in New York in the next 12 months

Load More

Load More

The US has retained a lead in the global art market for most of the last 50 years, supported by one of the world’s largest bases of HNW and upper-middle income wealth in the world, as well as a highly developed cultural infrastructure, support services, and network of expertise. Its growth has reflected shifts in economic power in the late 19th and early 20th century, which led to an influx of art being bought, primarily from Europe, by wealthy US collectors. During the 18th century, Europe and particularly Paris and London, were the key centers for the art trade and Europeans were the main buyers. However, one of the most significant developments in the art market post-1900 was the growth of the importance of US art dealers and collectors. A series of regulatory, political and economic changes in Europe from 1900 started to shift the market towards the US, where economic strength and buyer purchasing power rested. Buyers and sellers were also drawn to the more liberal trading regime in the US, as new taxes and other regulatory deterrents severely impacted the market share of former centers such as Paris. The frequently cited quote by London art dealer Joseph Duveen during the 1920s and 1930s was that “Europe had plenty of art and America had plenty of money”. The movement of art through sales to New York, as well as immigration during this period, soon developed a sufficient critical mass of objects within the US to support its own domestic circulation and trade. From the post war period to the present, generations of US artists also became significant names, which further led to the strong development of the US art trade.

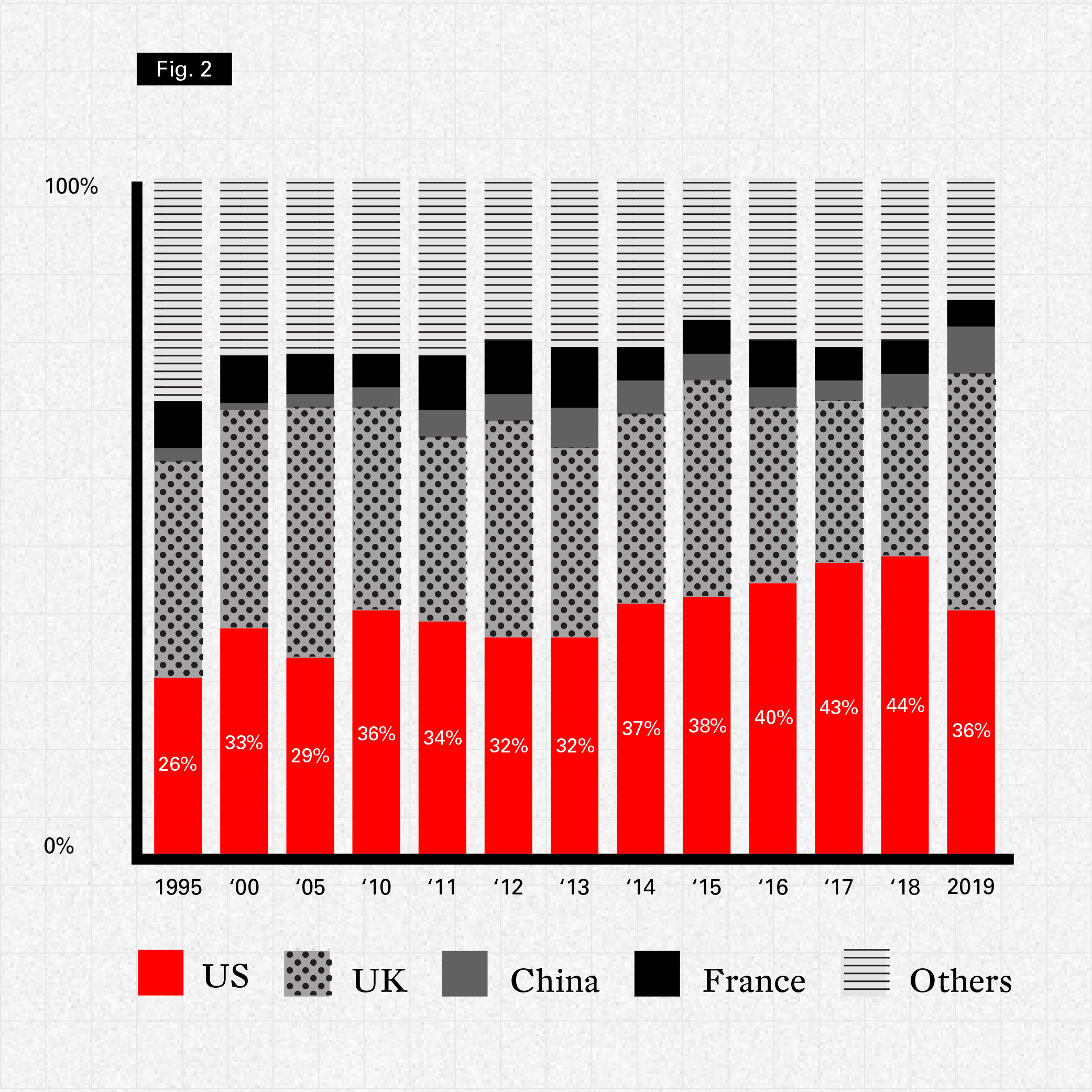

During the 1960s and 1970s, the major auction houses in New York began to thrive, attracting wealthy private collectors. Large galleries also began to flourish to accommodate an expanding buyer base, and dealer associations such as the ADAA were set up to promote standards in the profession. It was also during this period that New York began to establish itself specifically as the international center for more modern sectors of the art trade, including contemporary art, Impressionists, post-Impressionists and others (while London remained the main market for Old Masters and many decorative arts). The US became the premier market for art during this time, with a share of over 50% of the market in most years up to 2000. This margin has been diluted over the last few years, as China emerged as a third global leader, however, the US has maintained a dominant position almost every year since. In 2019, sales in the US art market reached a 44% share of the global sales by value, more than double the share of the next largest markets, the UK (at 20%) and China (at 18%)2.

Figure 1. The Global Share of the US Art Market by Value

© Arts Economics (2020)

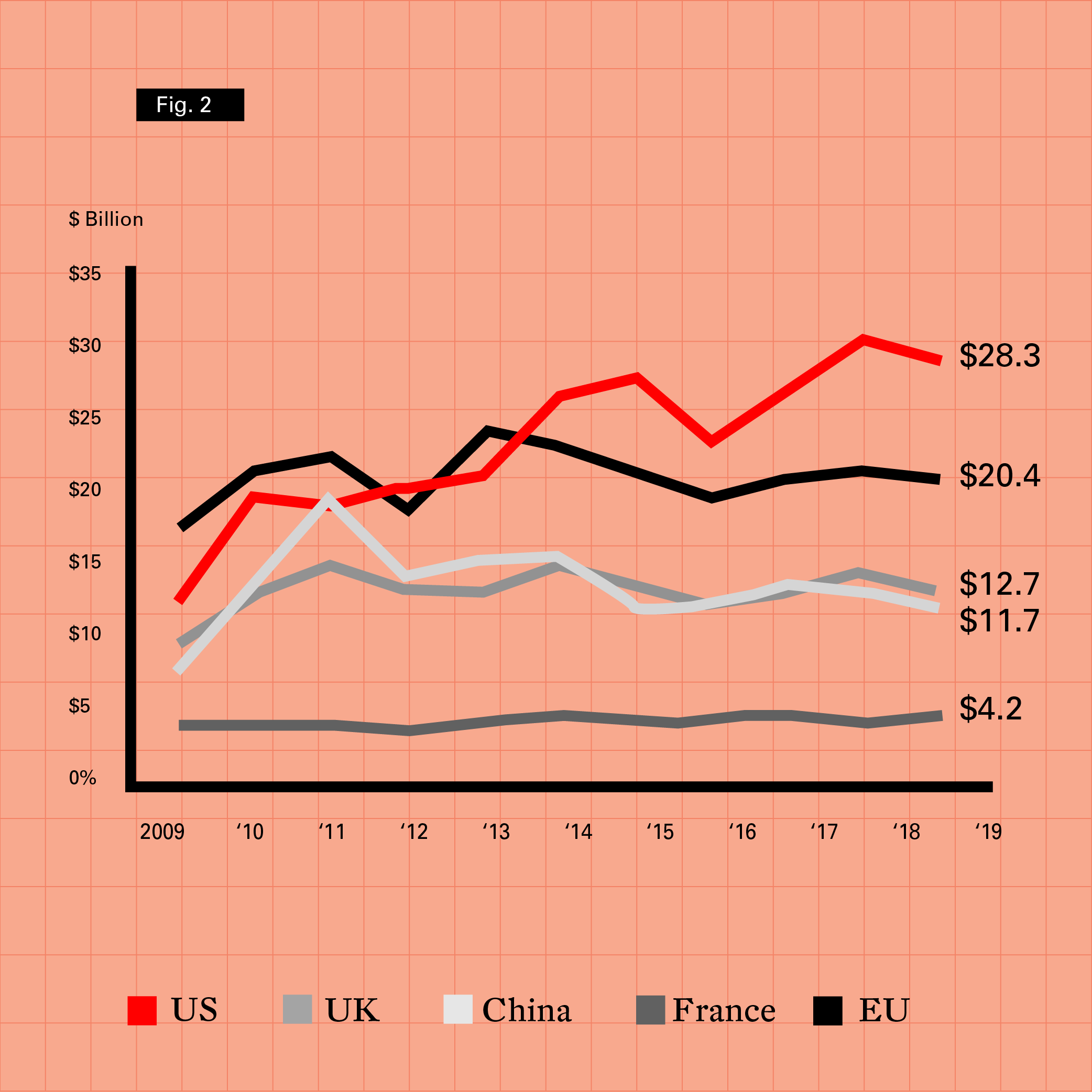

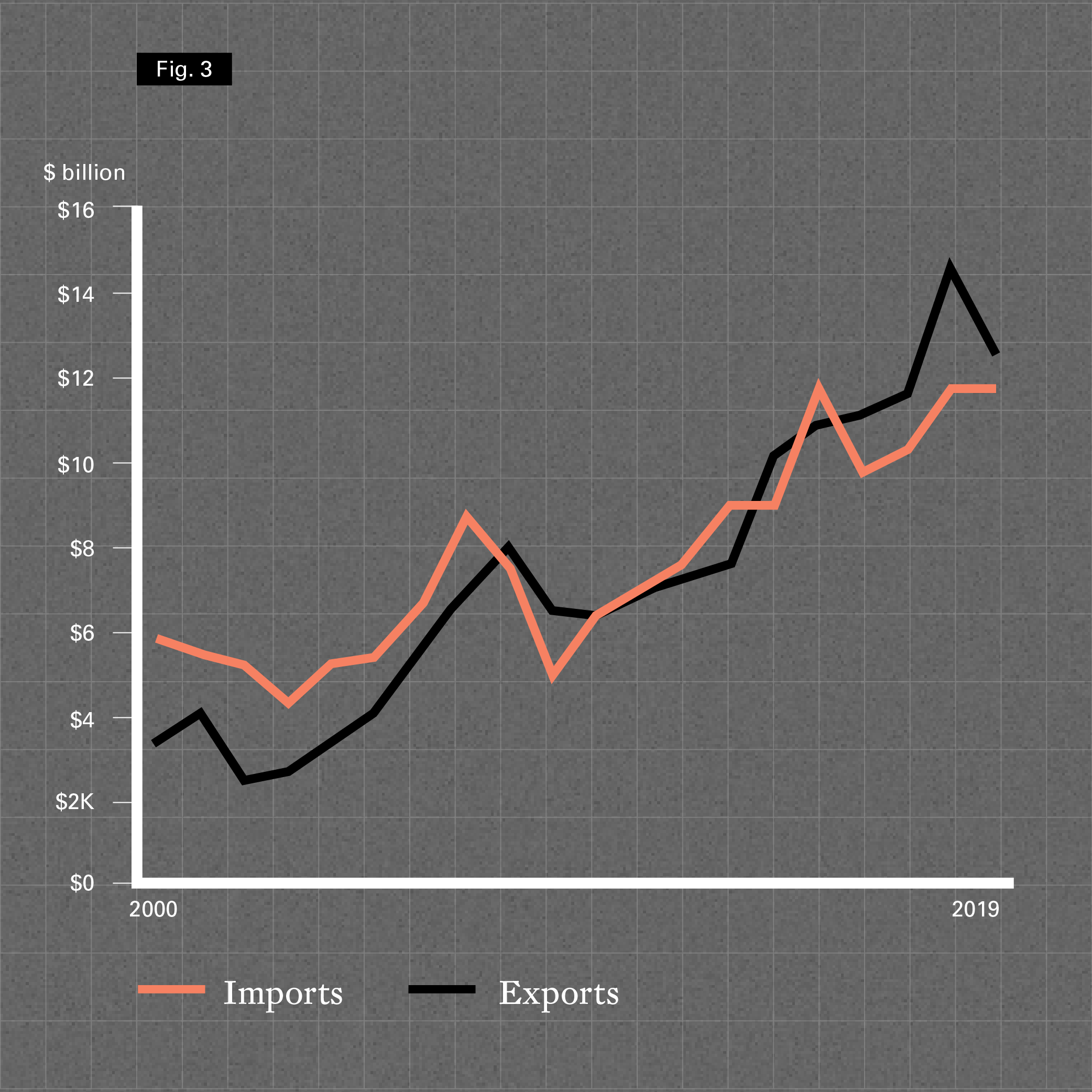

The US has been one of the strongest markets of the past decade, leading the global recovery of sales after the global financial crisis in 2010, with strong growth up to 2015. The market declined by 16% in 2016 as political uncertainties and a lack of high-end supply led to a deterioration in sales growth. However, the decline was short-lived and sales rebounded to reach a historic peak of just under $30 billion in 2018, twice the annual global growth rate, and a 31% increase in value over two years. In 2019, despite aggregate dealer sales maintaining positive momentum, a significant contraction in the auction sector (due to a reduction in the volume of very highly priced works on sale) brought the US market’s value down 5% year-on-year to $28.3 billion. Despite this decline, the value of US-based art sales in 2019 was still its second highest level in history. Values have also grown by just over 130% since their low point in 2009, more than twice the rate of any other market, including China (61%) and the UK (42%).

Figure 2. Sales in Major Global Art Markets 2009-2019

© Arts Economics (2020)

It is estimated that New York has accounted for at least 90% of the value of sales in the US market in most of the last 20 years3. It has acted both as a hub for domestic sales of art throughout the US as well as the key center for the international exchange of art between the US and external trading partners (see Chapter 5). A key factor driving the dominance of the US art market in terms of value, and New York as a global hub, is that it is the primary location for sales of the highest priced art in the world. Most sales of multi-million-dollar art at auction are carried out in New York, and most of the largest galleries in the world are based there.

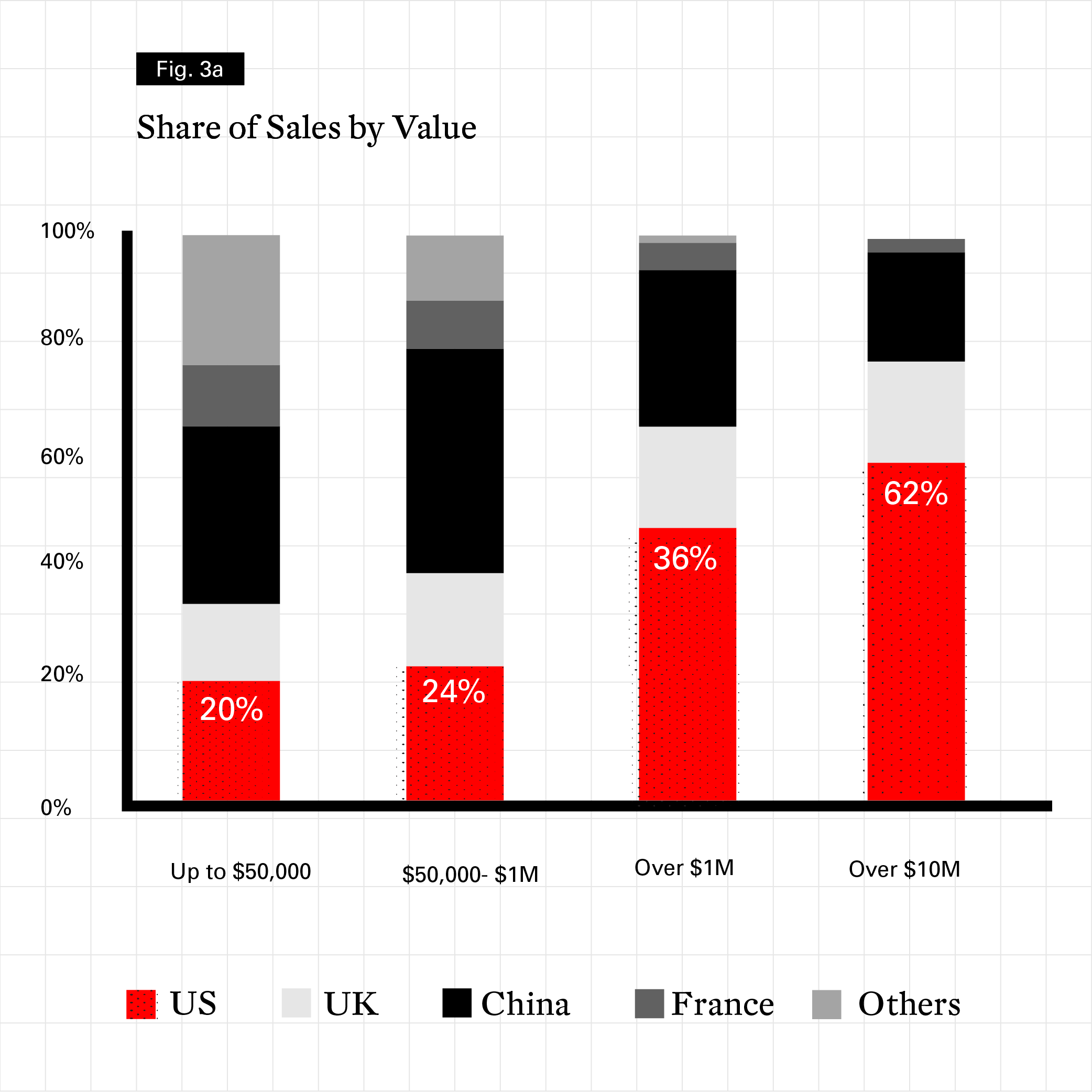

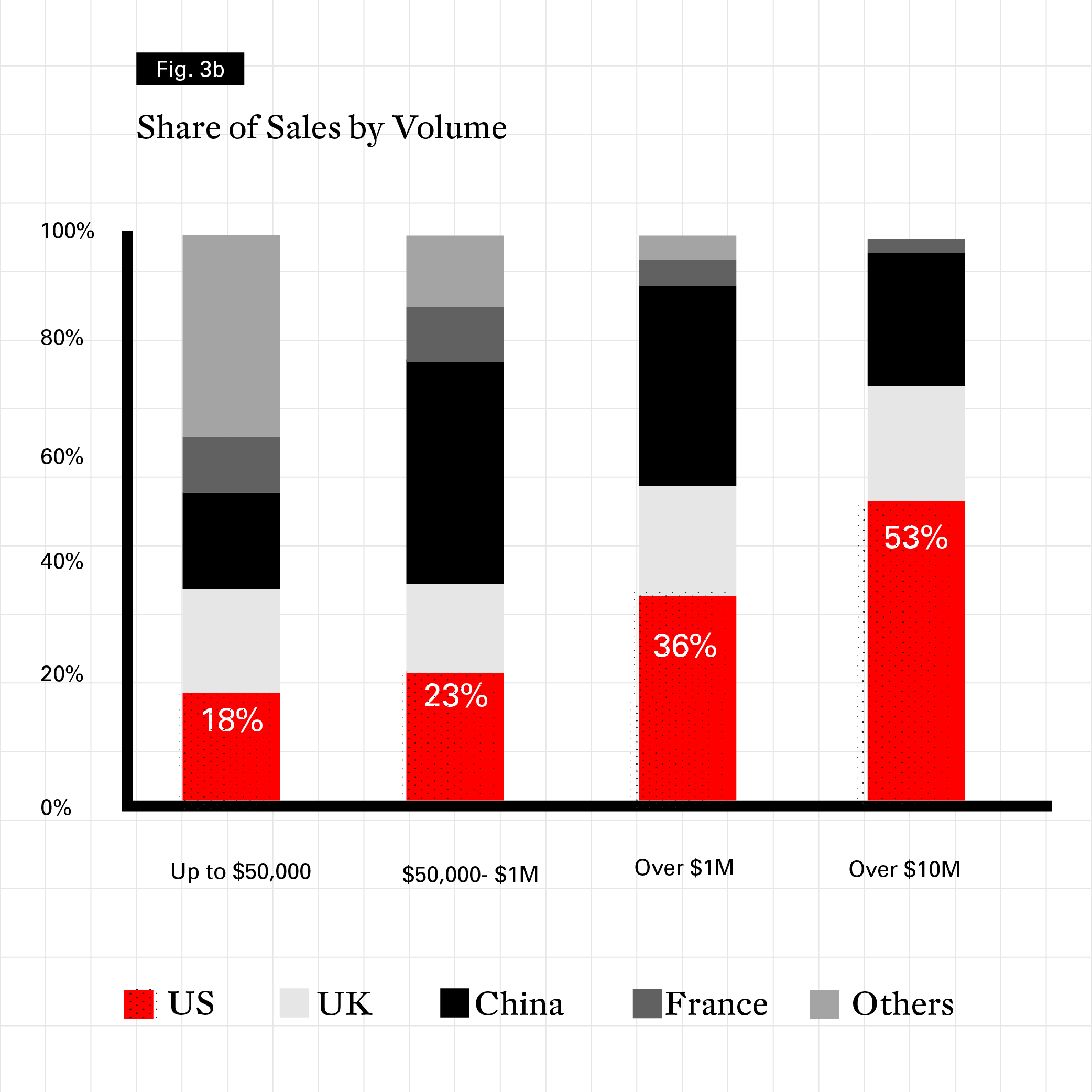

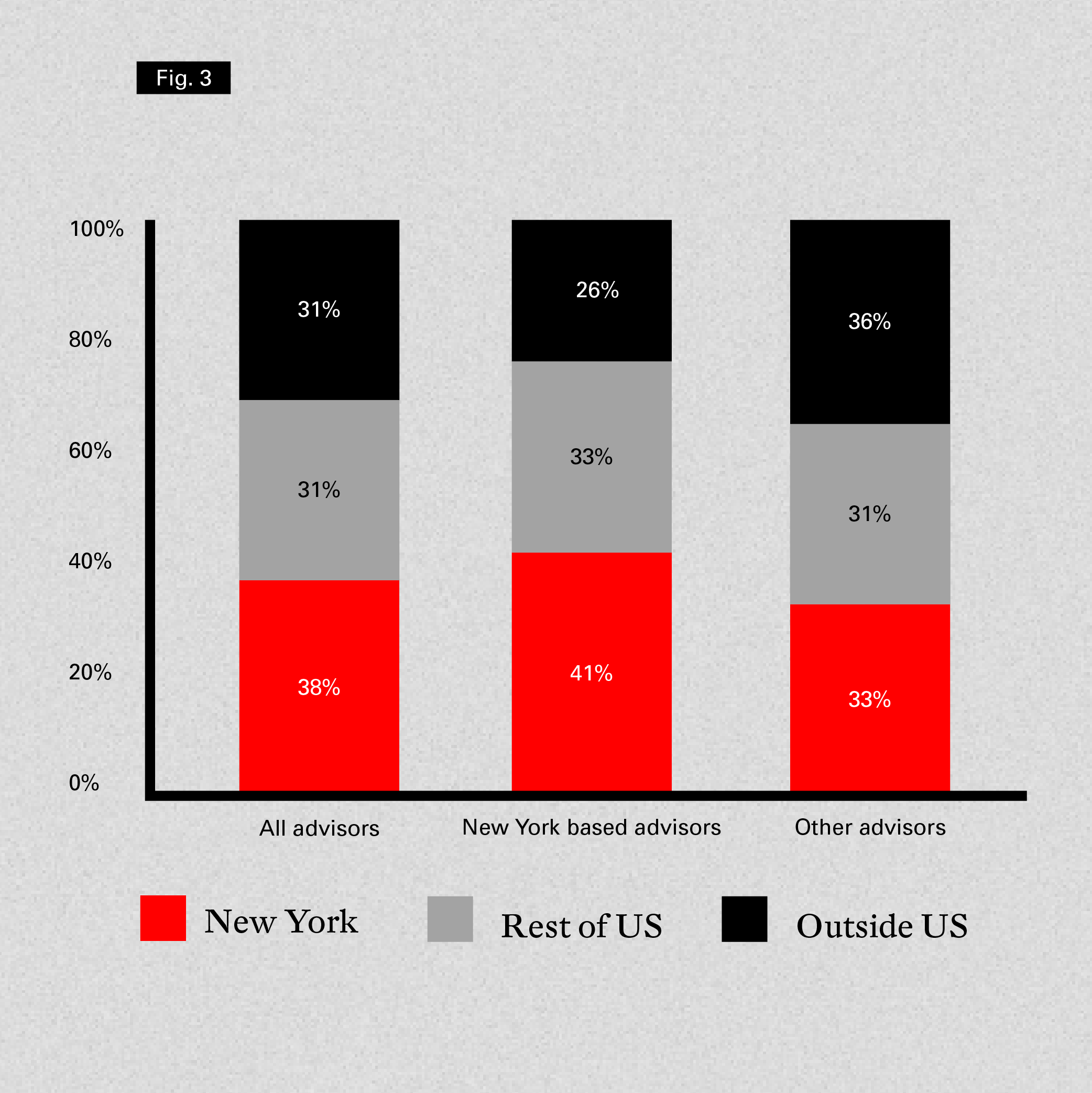

While the US dominates the aggregate market, using fine art auction sales, Figure 3 shows its escalating importance at the high end of the market: as price levels rise, the global share of the US expands. In 2019, it accounted for nearly half of all the lots sold at auction over $1 million and 62% of the lots sold for over $10 million, with all of those sold in New York.

Figure 3. Fine Art Auction Transactions by Price Levels in 2019

© Arts Economics (2020) using data from Artory

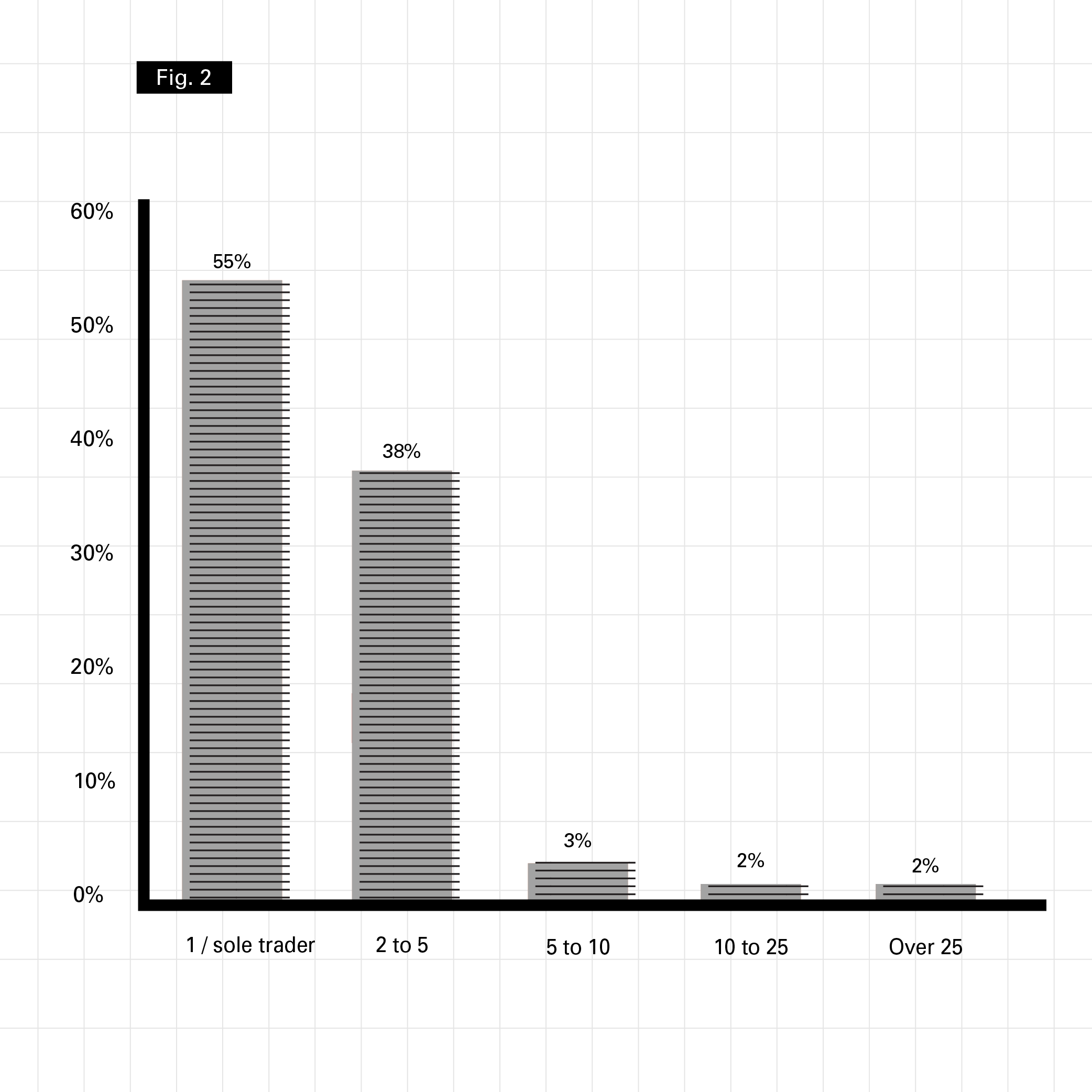

The US art and antiques market comprises over 78,000 businesses. These include auction houses, online auction and retail companies, antique dealers, galleries, private dealers and art consultants.

In 2019, there were an estimated 4,000 auction houses selling art, antiques and collectibles with about 600 selling art and antiques on a regular basis. Of these, at least 30% were based, or held offices, in New York. There is a smaller subset of about 150 auction houses that focus more exclusively on fine art and around 25 of those major companies have bases or headquarters in New York.

The gallery and dealer sector comprises about 74,000 businesses including art, antiques and collectibles galleries and private dealers. Focusing on art dealers only, there were around 38,590 businesses in the US, including just over 4,800 companies with employees and 33,780 non-employee businesses (that is, small businesses including sole traders, partnerships and other business forms with no paid employees).

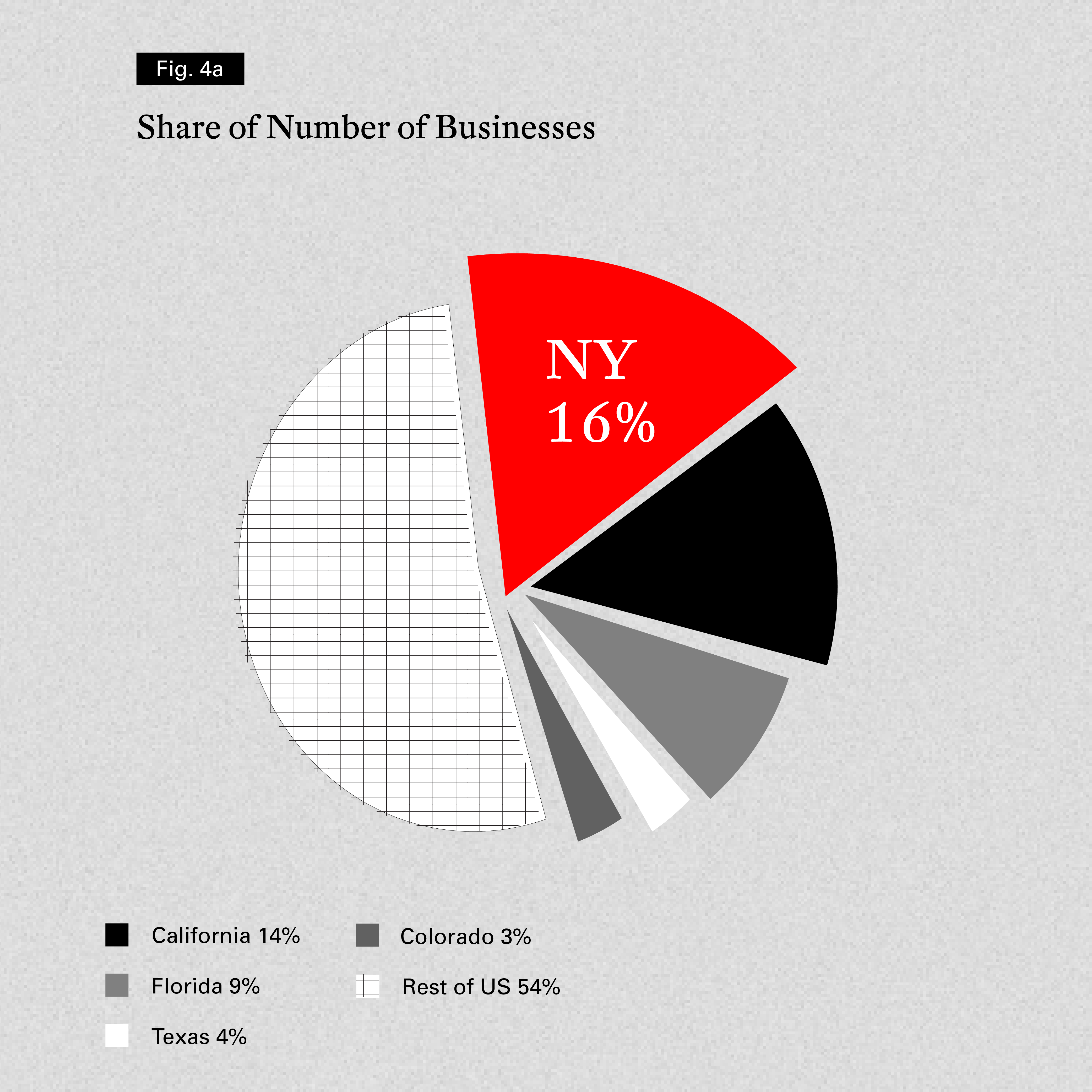

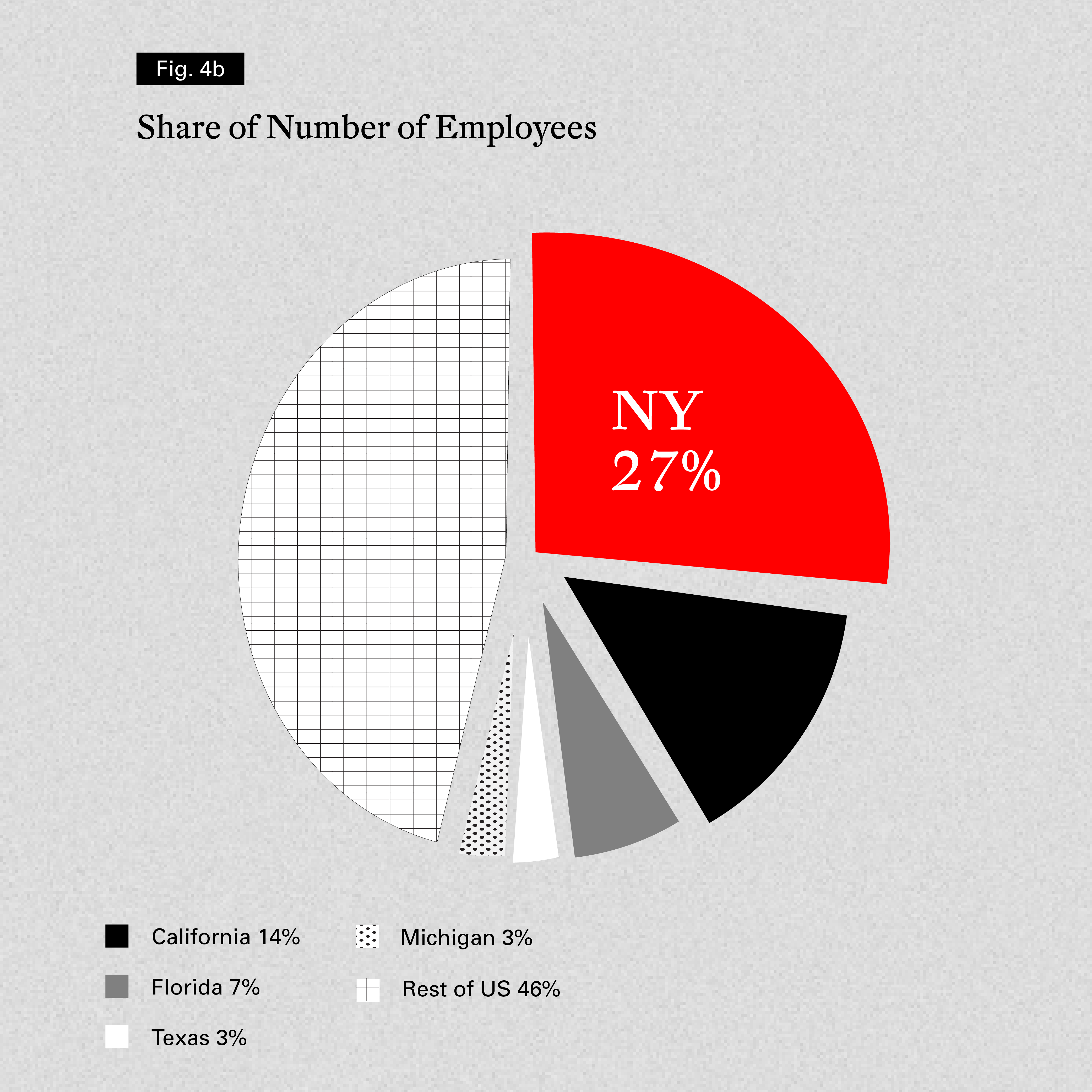

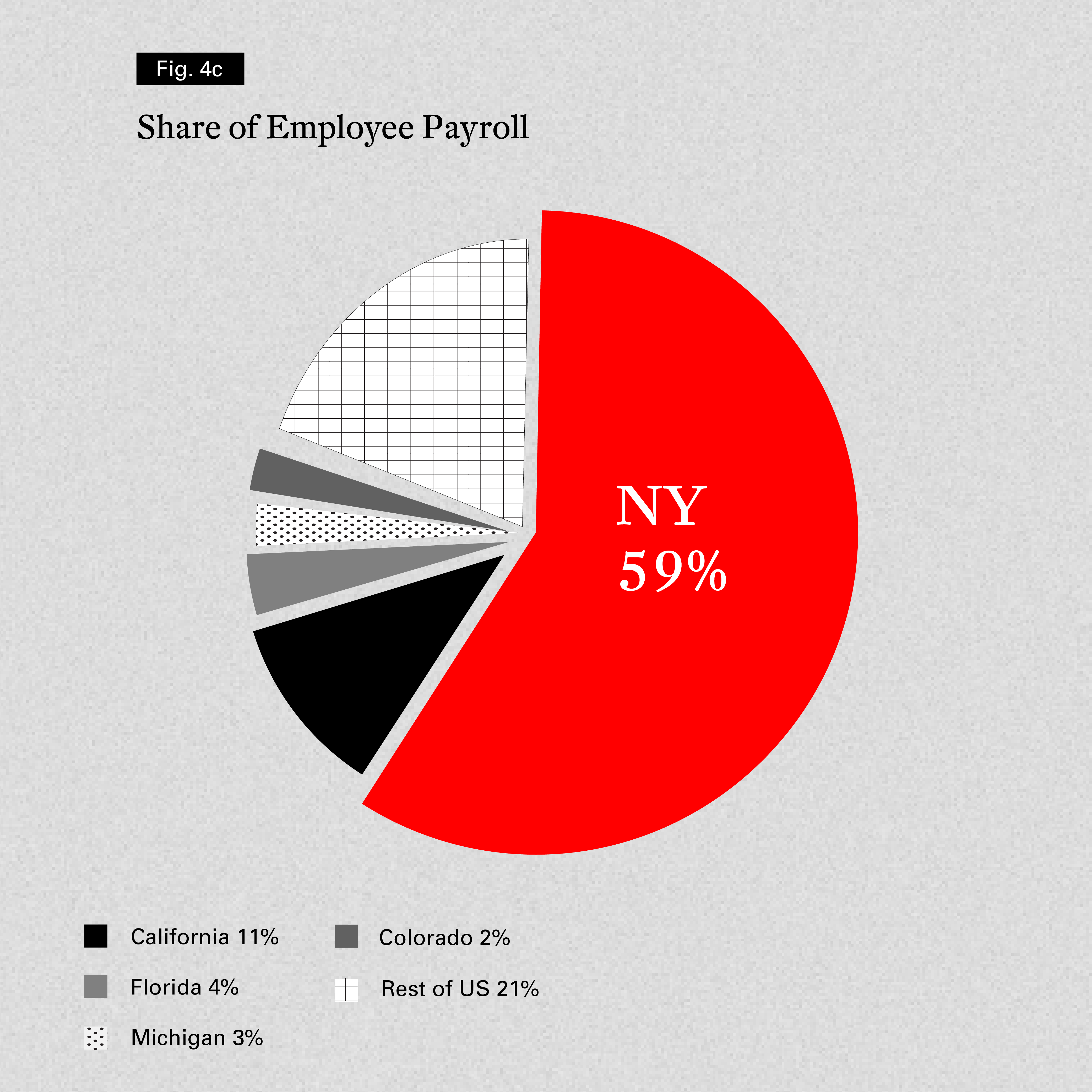

Considering only galleries and dealers with employees, New York accounted for the largest number of businesses in the US, with a 16% share of all art dealer businesses in 2019, with California the next largest state with a share of 14%. However, the share of the number of firms understates the dominance of New York galleries in terms of their economic weight. The galleries in New York are also generally larger and employ significantly more people than any other state. In 2019, New York galleries accounted for 27% of all employees in the sector in the country. This share of less than one third of the nation’s employees also accounted for over half (59%) of the payroll generated by this sector. This underlines the fact that New York dominates, not simply in number, but also in terms of being home to the top-tier and highest-end galleries in the US.

Figure 4. Art Dealer Businesses in the US by State in 2019

© Arts Economics (2020), estimates with data from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics

Artists are the most fundamental part of the art market’s infrastructure as the essential source of supply, and New York hosts a thriving contemporary art market, supported by the work of local and international artists.

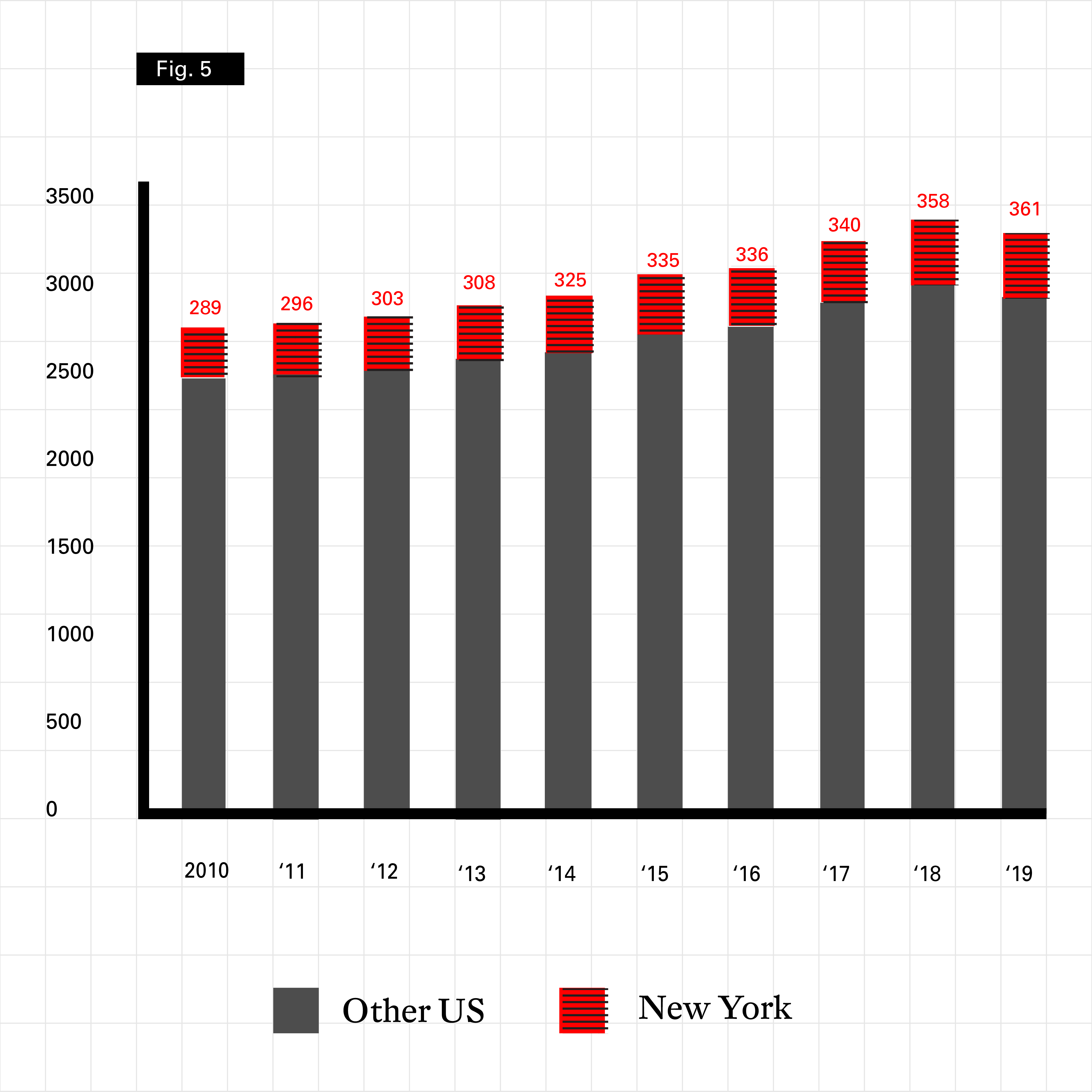

In official statistics, artists are included in the wider industry category of ‘arts, entertainment, media and sports’. The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) reported that this wider sector registered just over 2 million employees in the US in 2019, including almost 1.3 million ‘artists, designers and related workers’. Including self-employed workers in the sector, the total for the industry from the BLS Current Population Survey was estimated at 3.3 million in 2019, with numbers having risen 19% in ten years from just under 2.8 million in 2010, outpacing growth in total US employment over the period (which advanced 14%). The dynamism of this sector is even more evident over the longer term, with an increase in employment of 60% from 1995 versus less than half that rate (24%) across all US industries. It is estimated that New York accounts for around 361,000 jobs in the wider arts sector, or 11% of the total, and this share has not fluctuated more than plus or minus 1% since 2000.

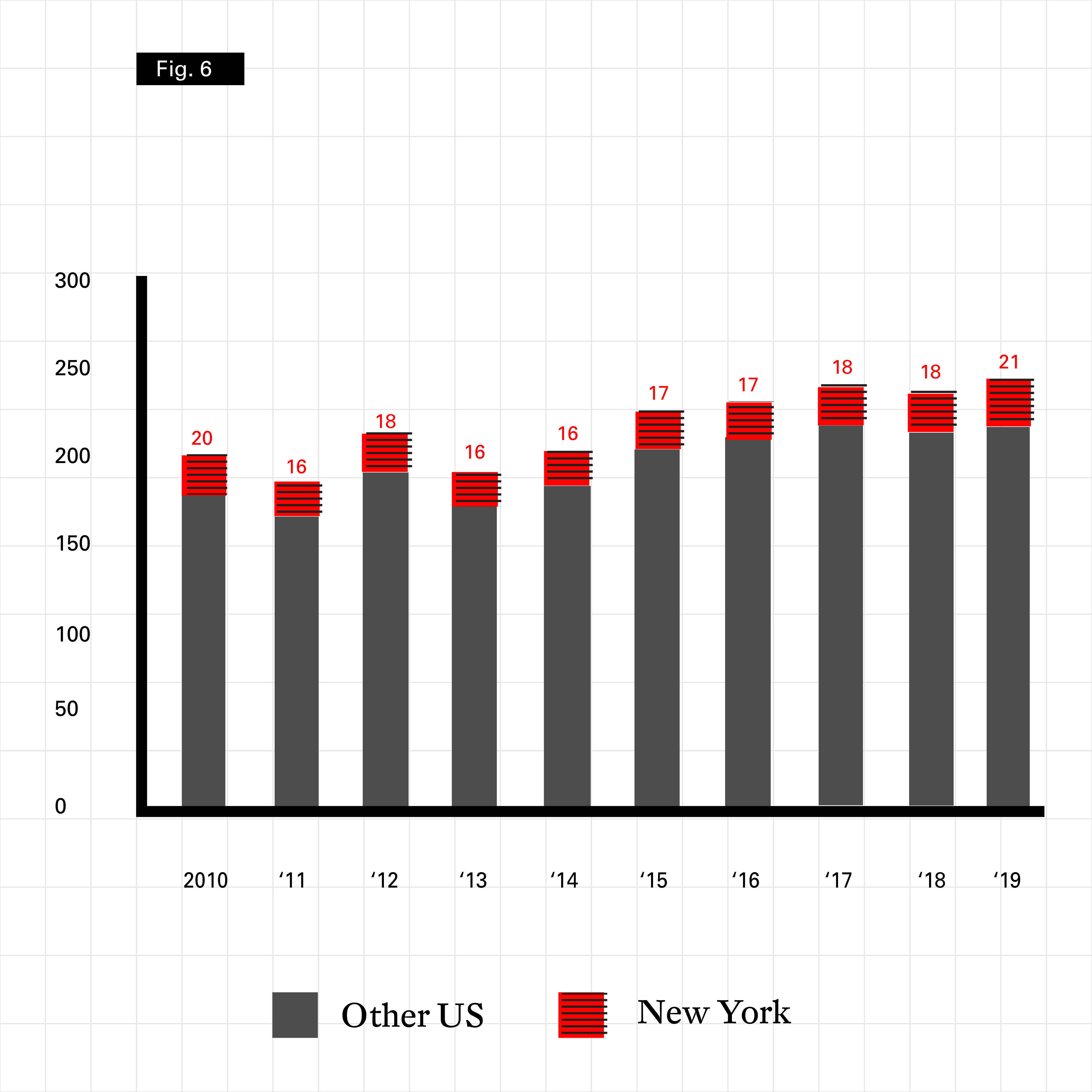

Looking more specifically at artists (and excluding designers and other related artistic workers), official statistics show 248,000 artists working in the US in 2019, and over 21,000 of those working in New York, or 9% of the national total4. While this is a significant share, it has declined over time (from a 12% share in 2000), and the number of artists based in New York has grown only 6% in the ten years from 2010 to 2019 (versus 27% nationwide). Looking only at the numbers of employed artists (excluding the self-employed), the number of artists has actually fallen by 9% since 2010 in New York and by 14% since 2000. This not only indicates more artists moving into self-employment, but also a drain of artists out of New York, possibly due to the rising costs of living and working there, which are recurrently cited as issues by artists and galleries.

Figure 5. Employment in the Wider Arts, Entertainment, Media and Sports Industry (Numbers Employed and Self-Employed)

© Arts Economics (2020), estimates with data from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics

Arts and cultural workers have been acutely affected by the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, particularly as many artists are self-employed. Although detailed occupational data is only available annually, data from the wider arts sector shows that self-employed arts workers have fared worse than employed workers during the crisis. From the third quarter of 2019 to the third quarter of 2020, aggregate employment in the wider ‘arts, design, entertainment, sports, and media occupations’ fell 12%. While aggregate self-employed jobs in the sector stayed relatively steady for the first half of the year in 2020, after three months of decline from May, the latest monthly data comparing August 2019 to August 2020, shows that the number of self-employed jobs in this category fell by almost 37% (from 521,000 to 330,000). Given the continuing effects of the pandemic, this is likely to continue to fall for the remainder of the year.

Besides its importance for living artists, New York is also an important base for many major artists’ estates. Around 60% of estates and foundations for leading artists in the US based in New York5. New York is also an important hub for the collective activity of artists and the administration of artist rights. There are approximately 60 major artist associations dealing with the rights of visual artists, illustrators and art critics in the US. 24 of these are based in New York, including associations such as the Artists Rights Society, the Visual Artists and Galleries Association, the International Association of Art Critics, the National Sculpture Society and others, with a combined membership of over 206,500 artists and related members in 2020.

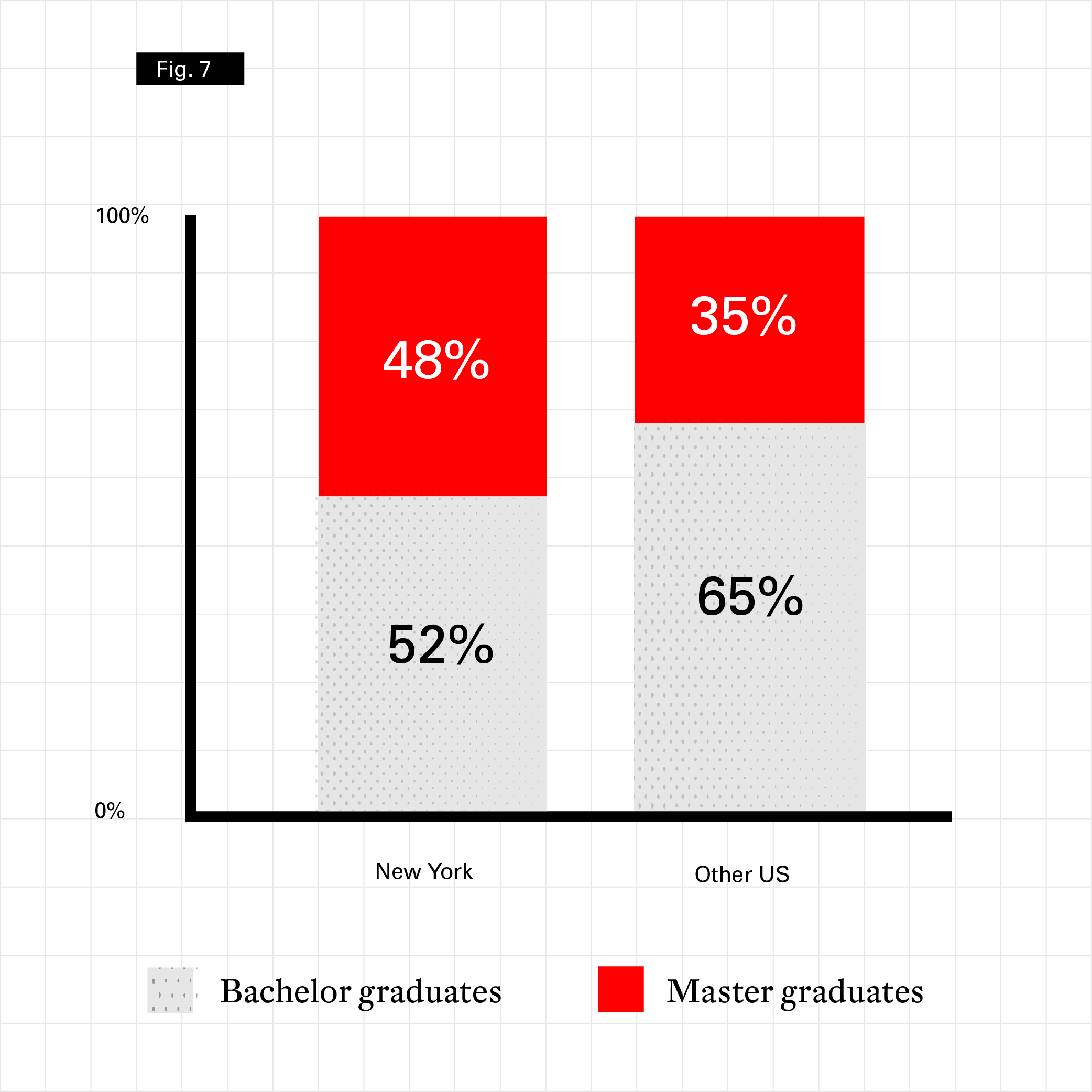

New York also produces a steady stream of arts graduates. A review of around 100 colleges ranked as leading in their fields in the US with programs relating specifically to visual artists and fine arts studies, revealed that 15 of the top institutions are based in New York6. These New York-based colleges produced close to 62,000 arts graduates in 2019, including 8% of the national total of those with bachelor degrees and 13% of Masters level graduates. There were also close to 183,000 students enrolled in these programs in New York in 2019 (9% of the national total of 1.9 million).

New York-based colleges had a significantly larger share of higher postgraduate studies graduates than the rest of the US, with 48% of the graduates of the top 15 institutions in the arts awarded Masters or higher qualifications in 2019, versus 35% in the rest of the institutions analyzed in the US.

Figure 7. Share of Masters versus Bachelor Graduates from Top US Fine Arts and Visual Arts University Programs in 2019

© Arts Economics (2020)

In recent years, art fairs have been a key channel for sales in the art market and a critical means of outreach for galleries to new collectors, allowing them to combine their bases of buyers and find new collectors from more diverse geographical locations. New York hosts a number of major events that draw large numbers of high-spending visitors over a short period of time. They inject substantial revenues into the city, supporting and creating a variety of economic and employment benefits.

From a database of 285 of the largest global art fairs, the US accounted for the greatest single national share (28%) with 80 events in 2019, with New York accounting for just over 40% of those. An analysis of the top 32 New York-based art fairs held in 2019 (including only those with at least 20 exhibiting galleries, some of which were from outside of the US) showed that on average these events brought together 92 exhibitors per fair with a range from 24 to over 360 galleries.

While these fairs merge New York-based and international galleries, they tended to maintain a relatively high share of local exhibitors. Across all of the fairs, 62% of exhibitors were from the US, with 38% from New York. There was a slightly higher share of international galleries at contemporary-only fairs, but US-based galleries still accounted for the majority, with 36% of those from New York. These figures indicate that many fairs in New York tend to have greater local participation by the gallery community in New York than is the case with some other major global fairs elsewhere. For example, less than 10% of the galleries exhibiting at Art Basel in 2019 were Swiss, while around 25% galleries from China exhibited at Art Basel Hong Kong in 2019. Although around half of the galleries at Art Basel Miami were from the US, there were only two registered as from Miami Beach in 2019. Similarly, less than one quarter of the exhibiting galleries at Frieze London were from the UK in 2019, and British galleries made up 35% of the exhibitors at Frieze Masters.

Art fairs have, up to now, served as critical part of the New York market infrastructure and a large share of dealer sales and collectors’ spending has been centered on these events. Global surveys of galleries in the contemporary and modern sectors carried out in 2020 showed that nearly half (46%) of their sales in 2019 were accounted for by art fairs. This experienced an exceptional reduction in share in 2020 to just 16% , due mainly to COVID-19 and the cancellation of most events, and larger galleries (many based in New York) showed some of the biggest reductions in sales and an even larger drop in share to 11% of total sales for US-based galleries8. It remains to be seen how New York-based fairs will fare in the next 12 months, but some galleries have shared anecdotally that they may be in a better position to support local fairs, as travel restrictions and other concerns linger. Some also noted that fairs in New York may be more effective given the strong base of domestic collectors should fairs need to rely more on local support.

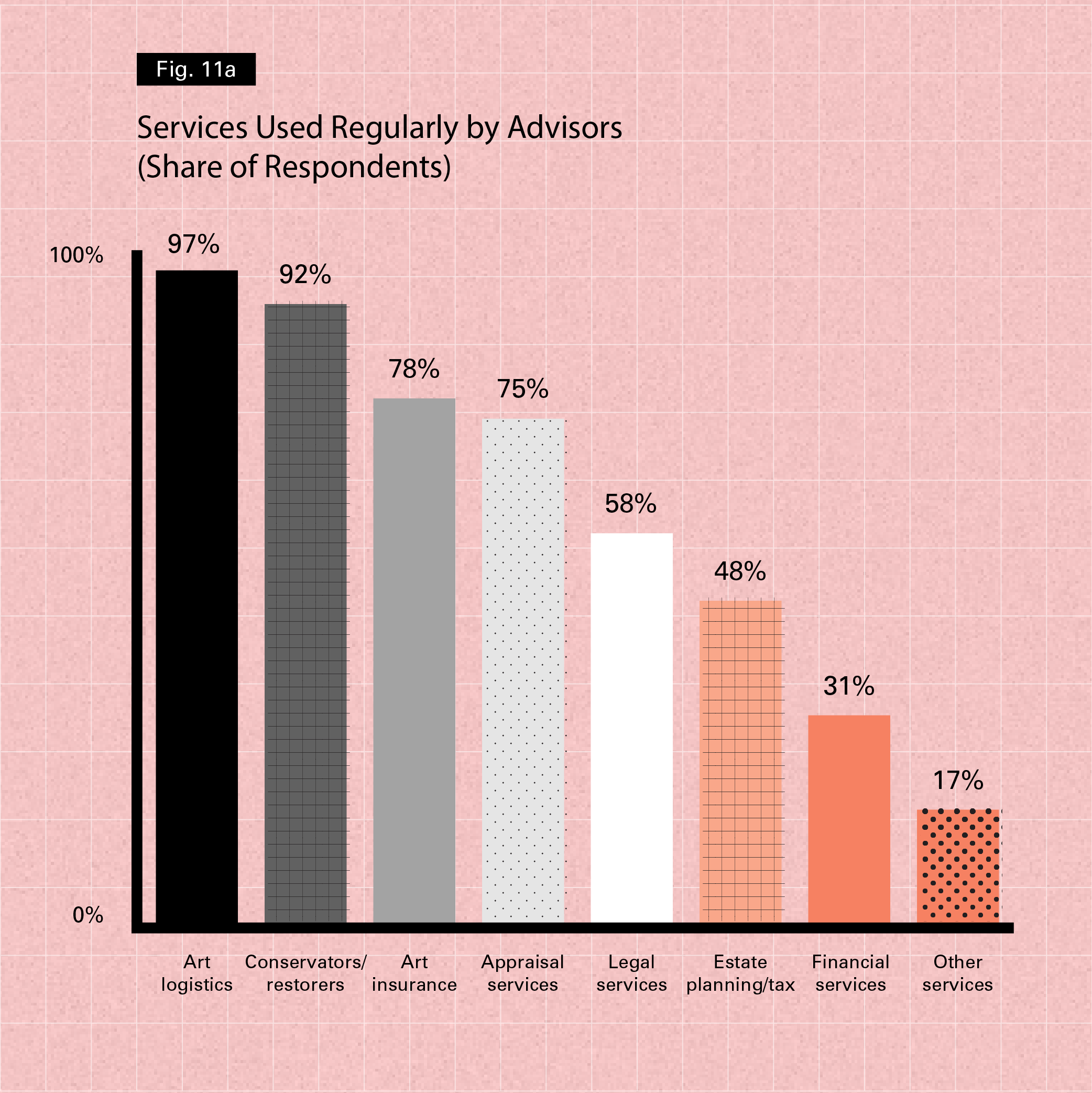

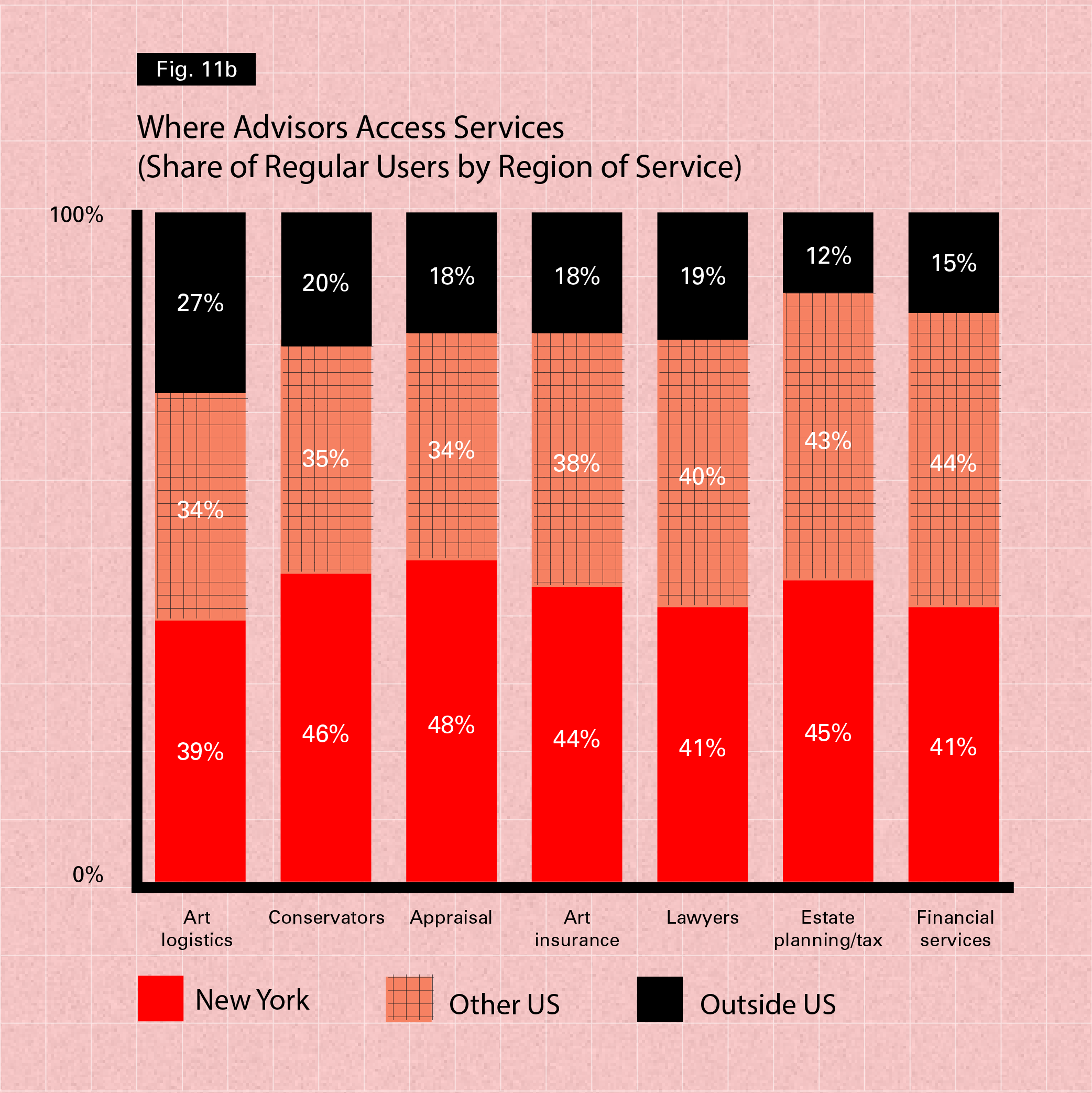

Apart from the art trade itself, there are a number of important businesses and institutions that interact with and support the art market. Many of these are specialized and niche businesses that have developed specifically around the art market, and would not exist or survive without it. These businesses have spawned an important segment of high knowledge jobs in New York, with most based around highly specialized skills and expertise.

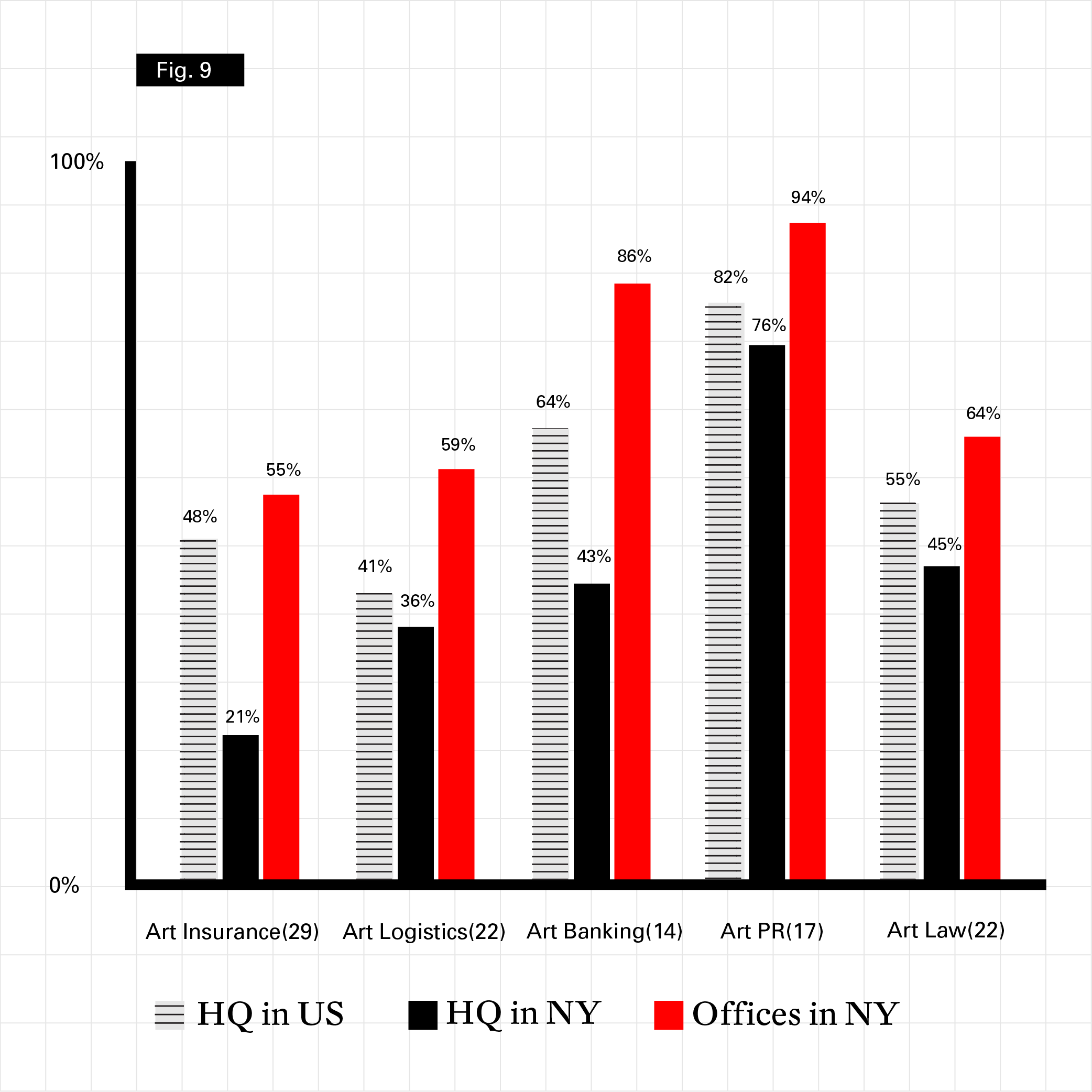

A review of media and industry sources in 2020 revealed that many of the best-known arts related services firms are headquartered in New York, or have offices there to serve local collectors and the art trade. These firms and their networks of experts provide a strong infrastructure in which the trade can operate as well as a significant economic impact for the state.

Figure 9. Share of Leading Art Services Firms Based in New York and the US*

© Arts Economics (2020)* Number of ‘top firms’ in each sample is given in parentheses

Museums are critical institutions in New York’s art infrastructure with multiple roles as collectors, vendors and exhibitors of art, as well as providing a network of highly specialized experts. The Institute of Museum and Library Services reported that there were just over 30,000 permanent non-profit museums in the US with 2,620 solely dedicated to art. 198 or 8% of those are based in New York and accounted for around 13% of the revenues of art museums in the US9.

New York museums receive some of the highest levels of private support in the US. The Association of Art Museum Directors reported that New York had the highest level of private support of all US states at $331 million, with the next highest being California ($163 million) and Texas ($79 million)10. They noted that philanthropy is a key driver for museum collections in the US, with more than 70% of acquisitions coming from donations, and around a third of museum revenue coming from private support.

Apart from the many experts in the art trade and museums, New York also has an important infrastructure of independent specialists and experts working in the art market. They provide important support and services to collectors and the art trade, and are part of the key advantages of New York as an art market hub.

Art appraisers are a critical part of the market’s expertise infrastructure, and the leading association for these experts globally is the Appraisers Association of America (AAA) which was founded in New York in 1949. The Association has a current membership of 819 expert appraisers, with 222 accredited and certified members in the tristate area of New York, New Jersey and Connecticut, and 146 in New York City. Membership is highly vetted, with accredited members requiring a minimum of five years’ experience and a peer review of three different professional appraisals. Certified appraisers are additionally required to carry out a seven-hour exam as well as having at least ten years’ experience in appraising. Both require 120 hours of education as a minimum, although most of the members have significantly more, and the AAA takes an active role in education, having created the Appraisal Institute of America in 1983 in New York, which runs a variety of appraisal studies programs and events.

While New York’s collectors often rely on dealers, curators or their own personal taste and due diligence to guide them, art advisors have also gained in importance over the last 20 years, and their role has become central in the New York and global art markets. Advisors come from a range of backgrounds, with many formerly in key positions within the art trade, such as former dealers, auctioneers or curators. Although there is no professional framework, qualifications or vetting of those who set themselves up as advisors or consultants, attempts have been made to establish professional standards and guidelines in the industry through setting up associations, such as the Association of Professional Art Advisors (APAA). This association was formed in New York in 1980 and has over 170 members and affiliates, including 137 from the US and 70 based in New York. The influence and interactions of art advisors in the New York art market is examined in more detail in Chapter 4.

The US is home to some of the world’s most established art collectors. Although it is impossible to say with precision how many collectors there are worldwide, it is estimated that there are over 500,000 mid-to-high level regular collectors of art and antiques. Estimates from experts in the art trade are that within that group, there are around 3,000 collectors at the very highest level, and at least half of these reside in New York.

A key strength of the New York art market is that it acts both as an entrepôt market or trading hub for global sales, while also maintaining a strong domestic trade supported by its local and transient upper-middle and high net worth (HNW) population. Although there are many reasons why the US has developed into the epicenter of the art trade, a fundamental factor is that it is home to the world’s largest population of HNW individuals, a significant share of whom are art collectors and many based in New York. While buying in China and other newer markets has expanded, most of the activity is supported by HNW individuals, which comprise a very small segment of the population. In contrast, more established hubs such as New York have stronger upper middle income wealth segments, which give depth to the trade, supporting the market at different levels and price points.

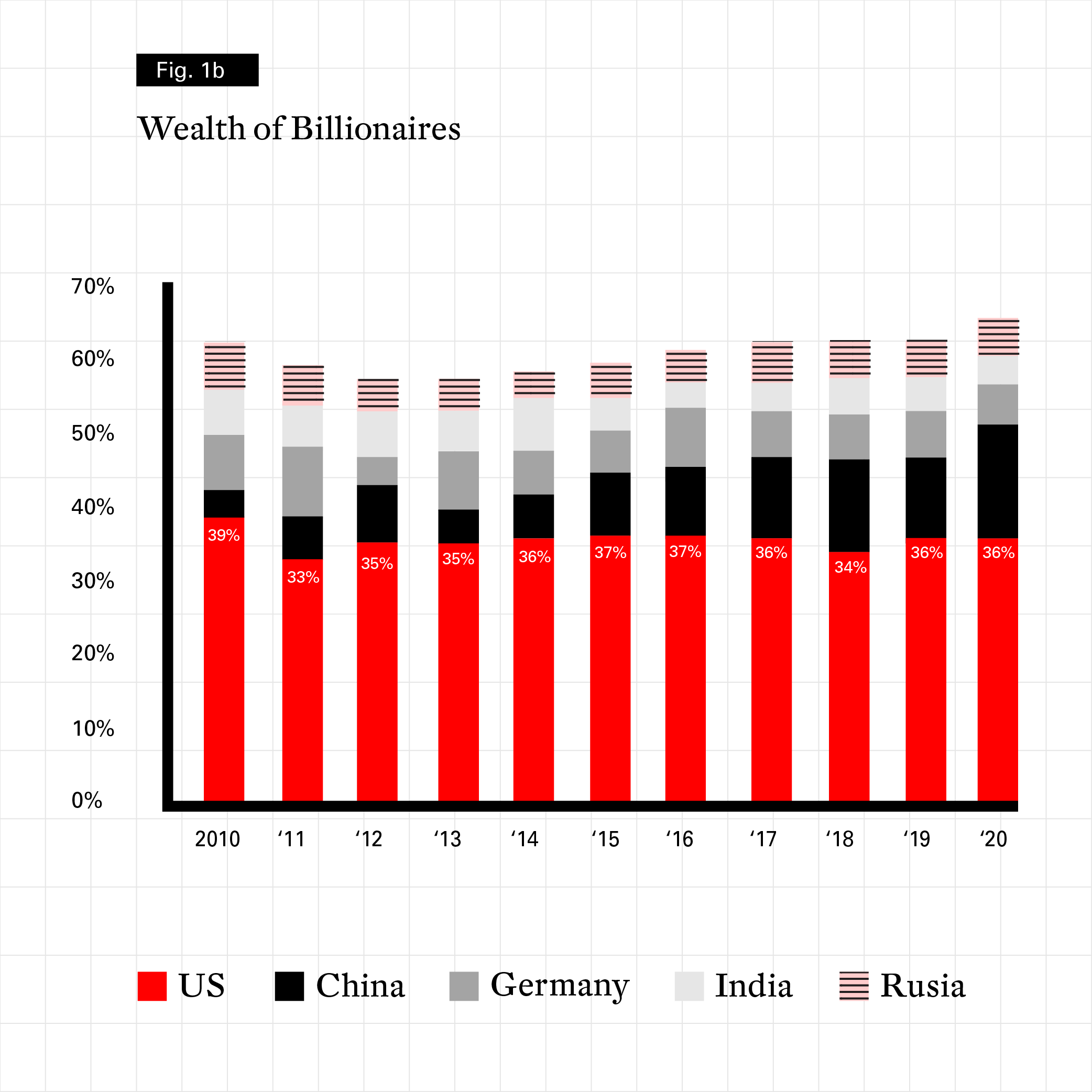

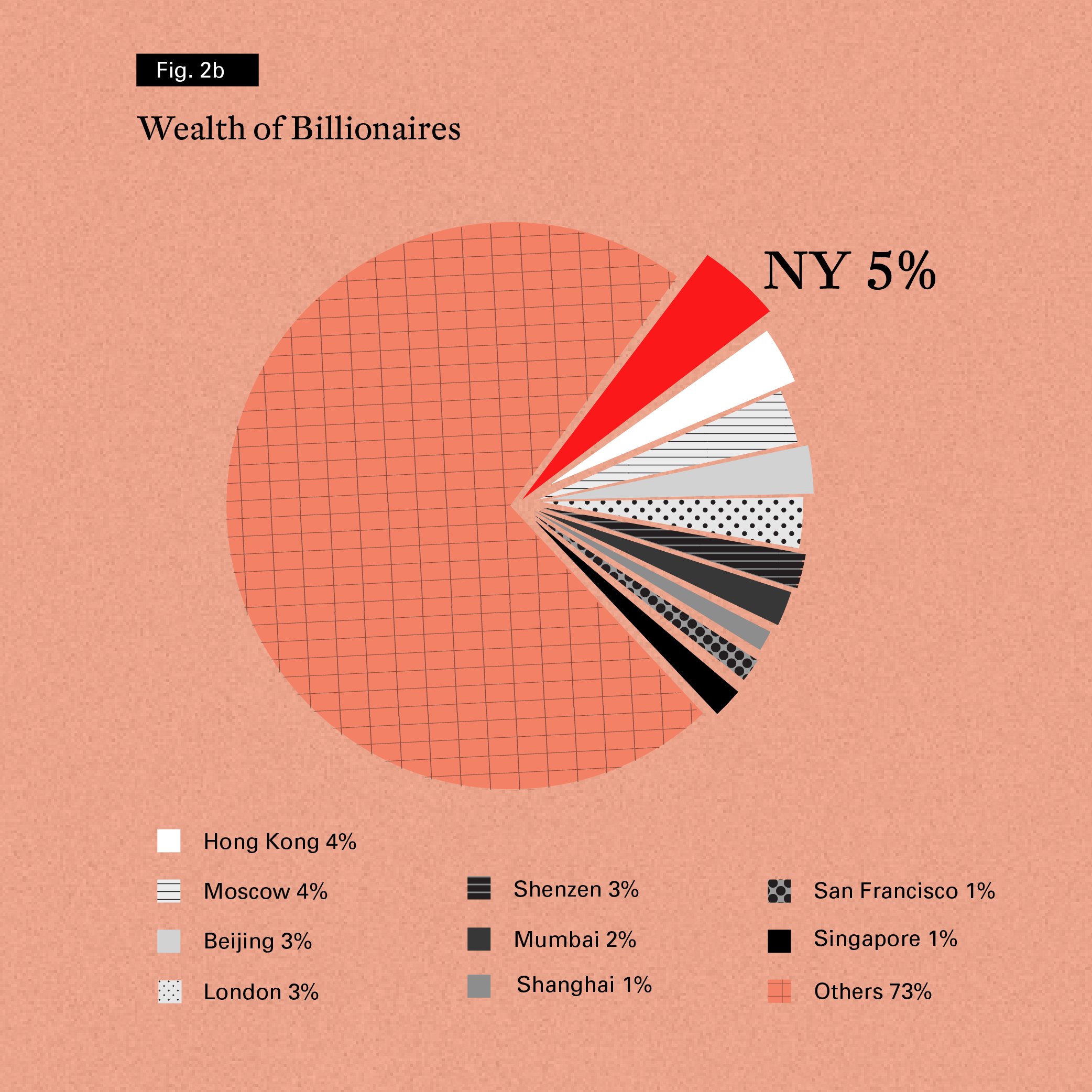

At the very highest tiers of global wealth, the world’s billionaires have an important impact on the size and distribution of the art market, and they have grown significantly and diversified geographically over time. However, despite the growth of wealth in Asia and other regions, the US maintains the highest number of billionaires worldwide, many of whom are important art collectors.

A key source of data for wealth at this level is the Forbes Billionaire List, which has recorded the number and wealth of the world’s billionaires since 1987. That year, the list commenced with 139 billionaires, including 49 from the US, but this figure has increased rapidly, as wealth and inflation have expanded over time. In the decade spanning from 2010 to 2020, the number of billionaires more than doubled in size from 1001 to 2095 and their wealth increased from $3.6 trillion to $8 trillion. In every year since the creation of the index, the US had the most billionaires worldwide. In 2020, they numbered 614, 29% of the global population of billionaires. US billionaires have also consistently accounted for the largest share of billionaire wealth, ranging from just under 30% in 1996 to a high of 45% in 2005. In 2020, they accounted for 36% of global billionaire wealth (an estimated $2.9 trillion).

Figure 1. Global Share of Billionaires 2010-2020

© Arts Economics (2020) with data from Forbes

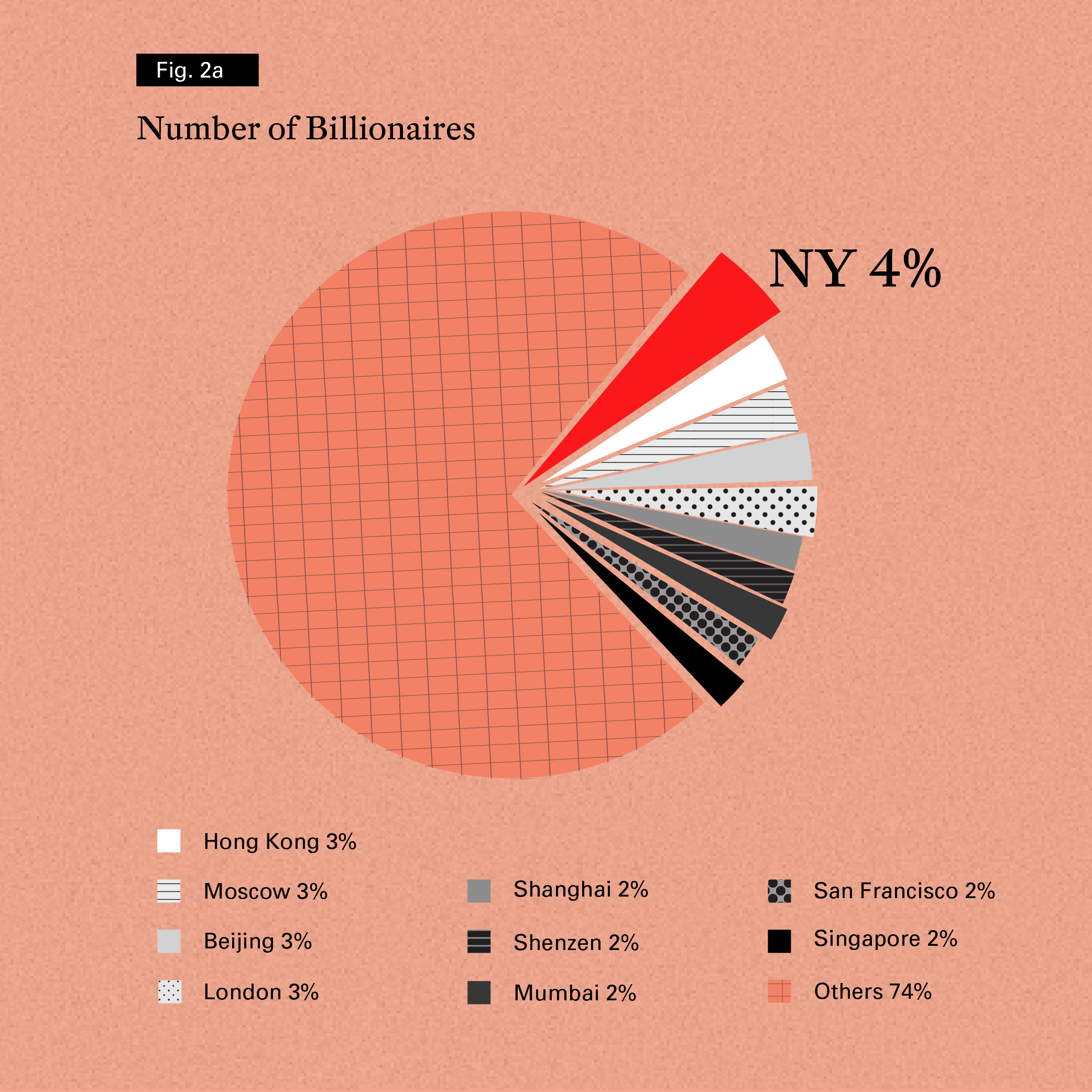

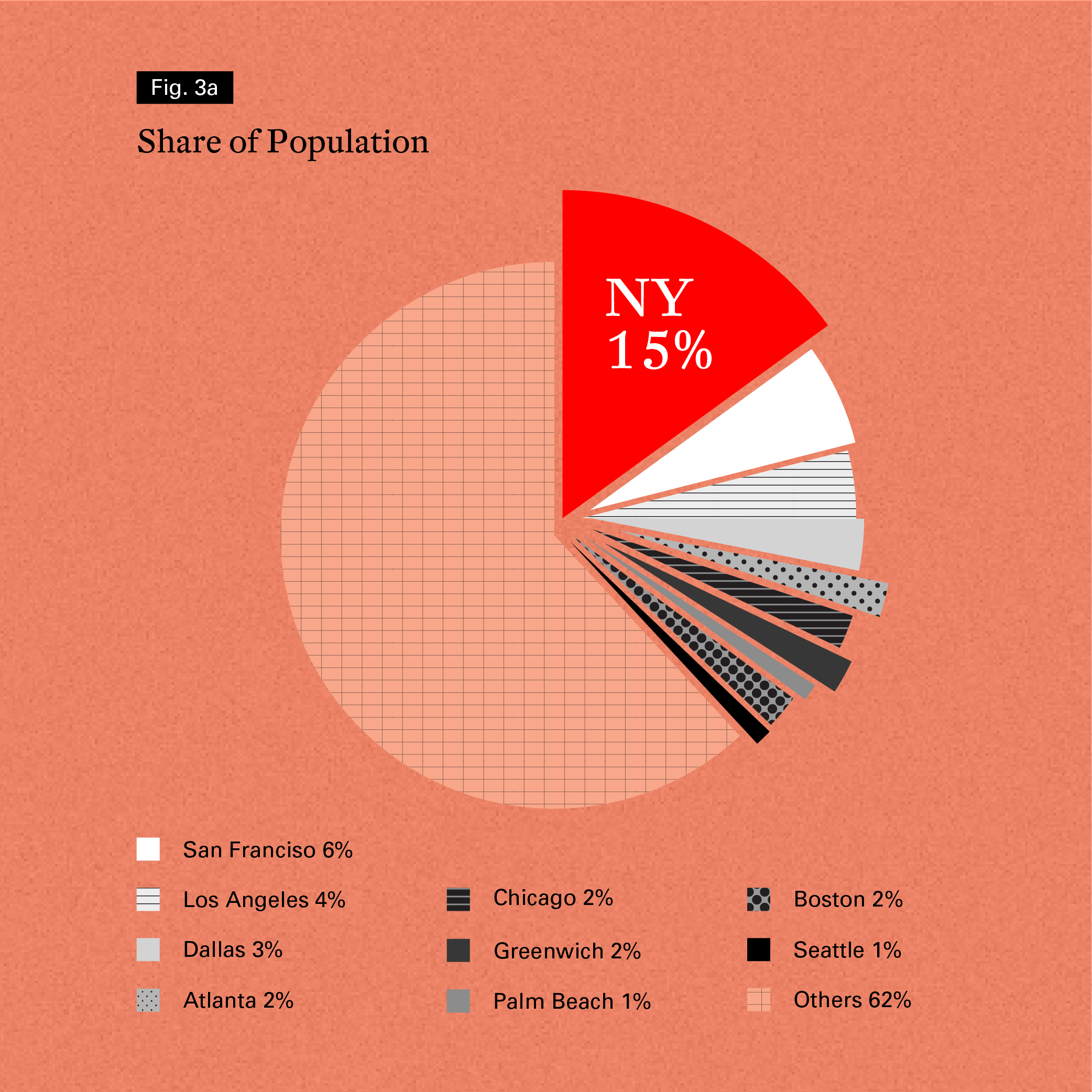

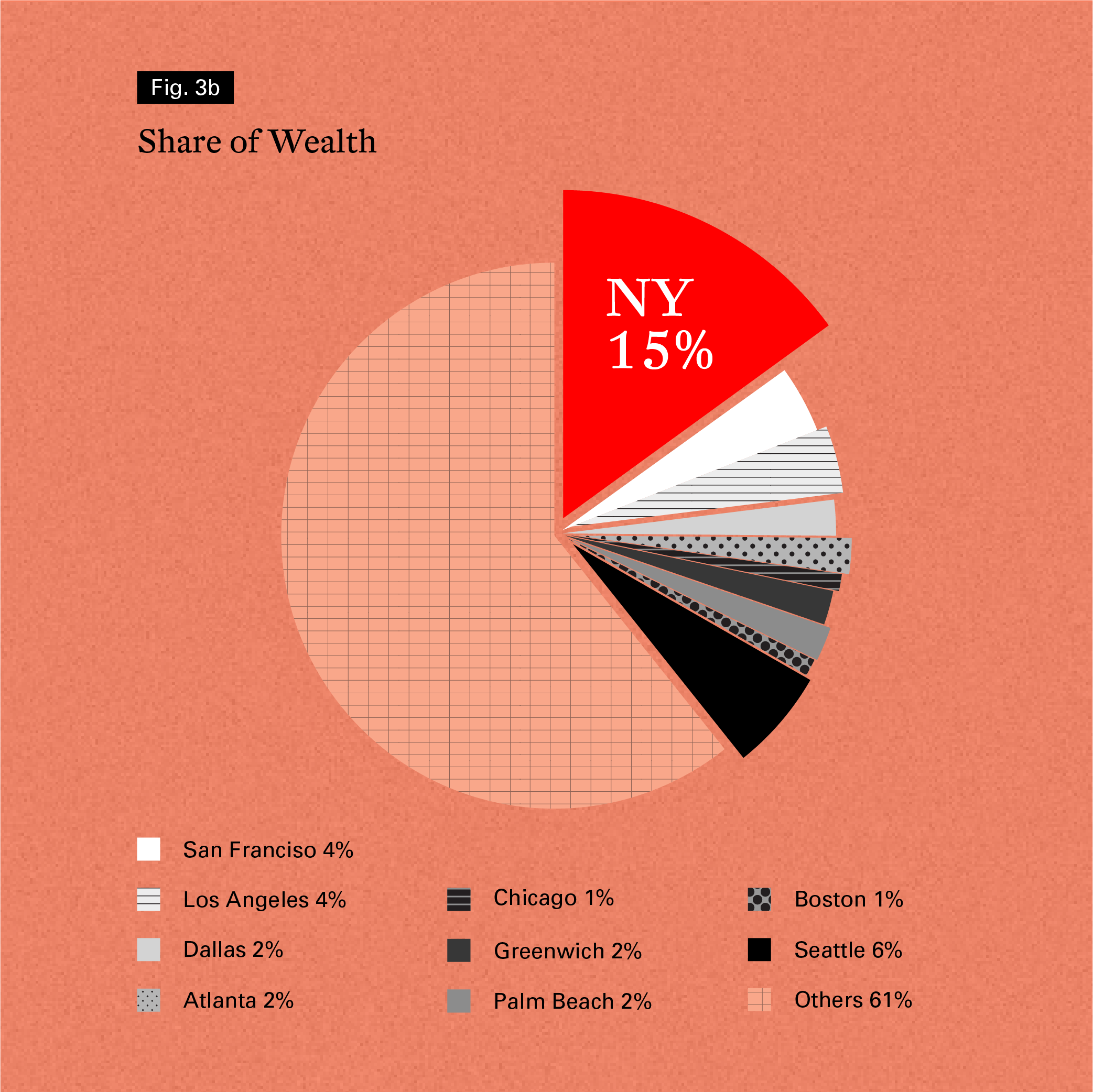

New York City is also the largest city in the world for both billionaire population and billionaire wealth, accounting for a 4% and 5% global share respectively in 2020. Within the US, New York has consistently had the highest number of billionaires, with Forbes registering 92 in January 2020, accounting for $424 billion in wealth (a 15% share of the US billionaire population and their wealth).

Figure 2. Share of Global Billionaires by City in 2020

© Arts Economics (2020) with data from Forbes

Figure 3. The Share of US Billionaires by City 2020

© Arts Economics (2020) with data from Forbes

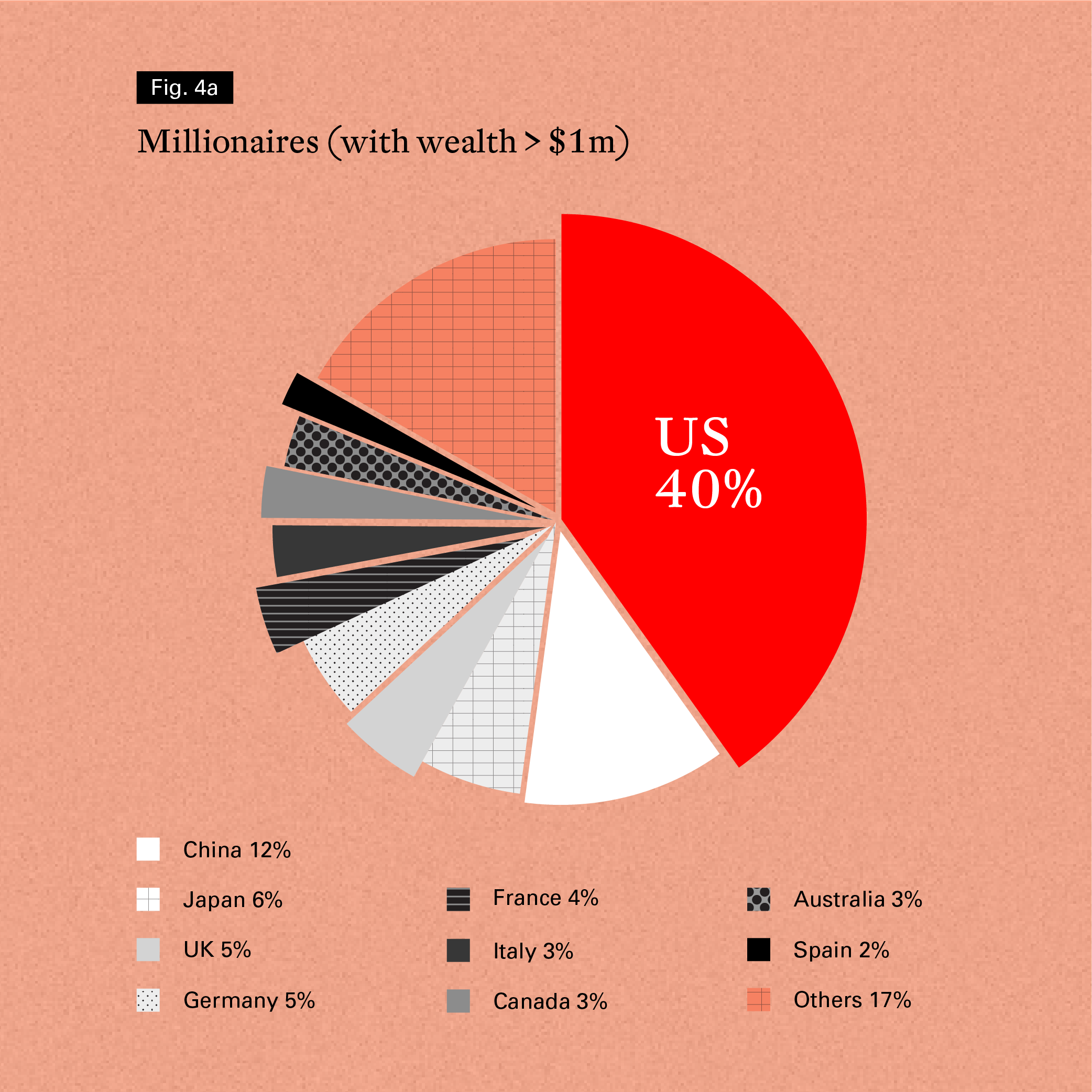

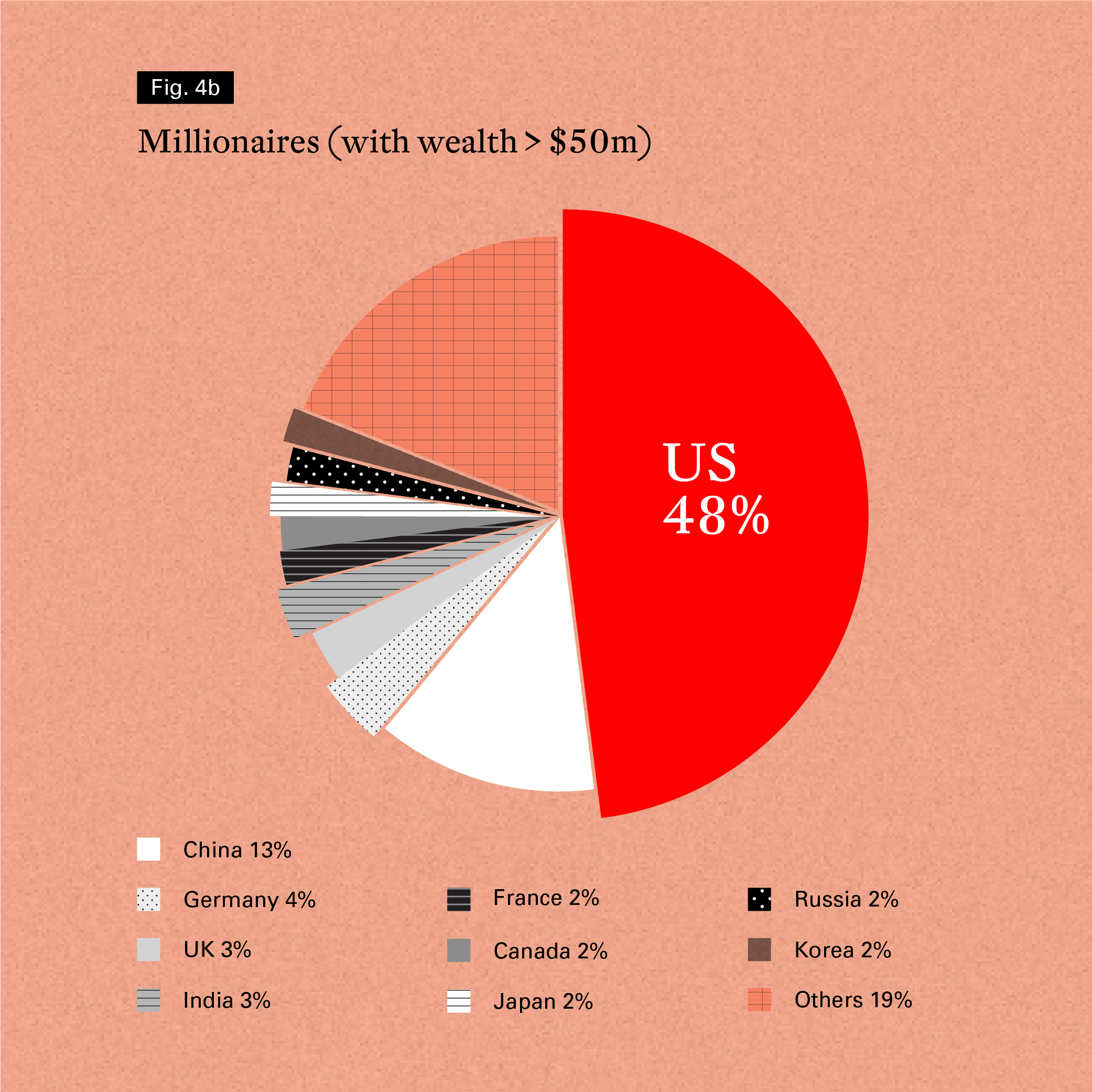

The US had an estimated 18.6 ‘dollar millionaires’ in 2019, making it the largest global national center for HNW wealth, as it has been consistently over the last 20 years, and accounting for 40% of the millionaire population worldwide11. An analysis of the global share of HNW wealth also shows that the share of the US expands as wealth levels rise. In 2019 the US accounted for a 48% share of the population of ultra-HNWIs with wealth over $50 million12.

Based purely on investible assets (excluding property and other non-financial assets), Wealth-X estimate that there are 8.7 million HNWIs with investible wealth in excess of $1 million in the US, and New York is home to just under 1 million of those. This makes it not only the largest center of millionaires in the US, but also the largest globally (and 65% larger than Tokyo, which ranks in second place)13.

Figure 4. Global Population Distribution of Millionaires

© Arts Economics (2020) with data from Credit Suisse

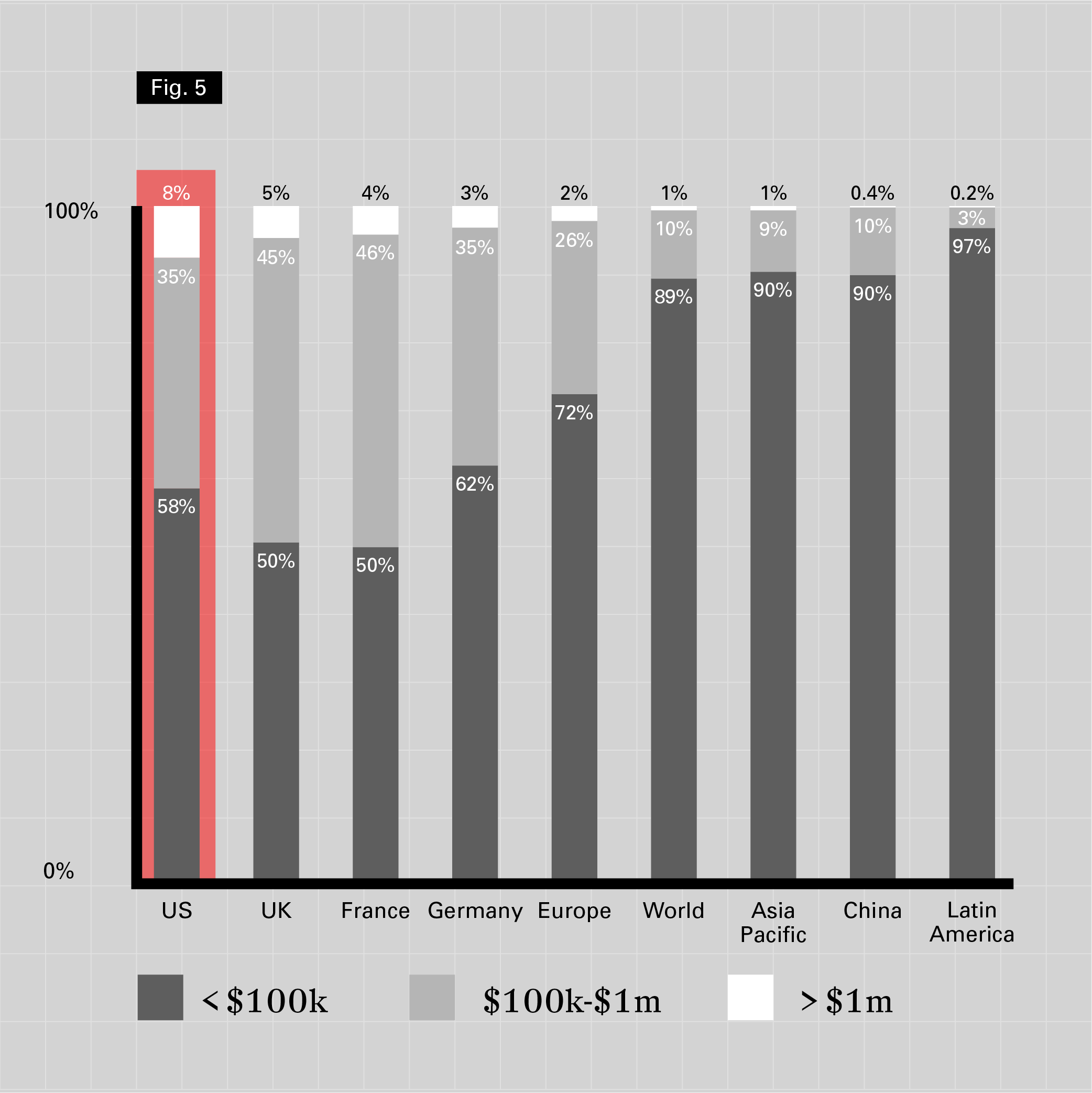

Apart from HNW wealth, which is critical at the top end of the art market, the US also has a large number of upper and upper-middle income households that help to support the market at different levels. The average wealth per adult in the US in 2019 was $432,365, six times the world average and considerably higher than other major art markets, such as the UK ($280,050), France ($276,120) or Mainland China ($58,545). The US has a higher share of its population in the $1 million plus segment than these countries, but it also has a large share of the population in the $100,000 and upwards segments (at 42% in 2019 versus the world average of just 11%).

Figure 5. The Share of National and Regional Populations by Adult Wealth Level (2019)

© Arts Economics (2020) with data from Credit Suisse

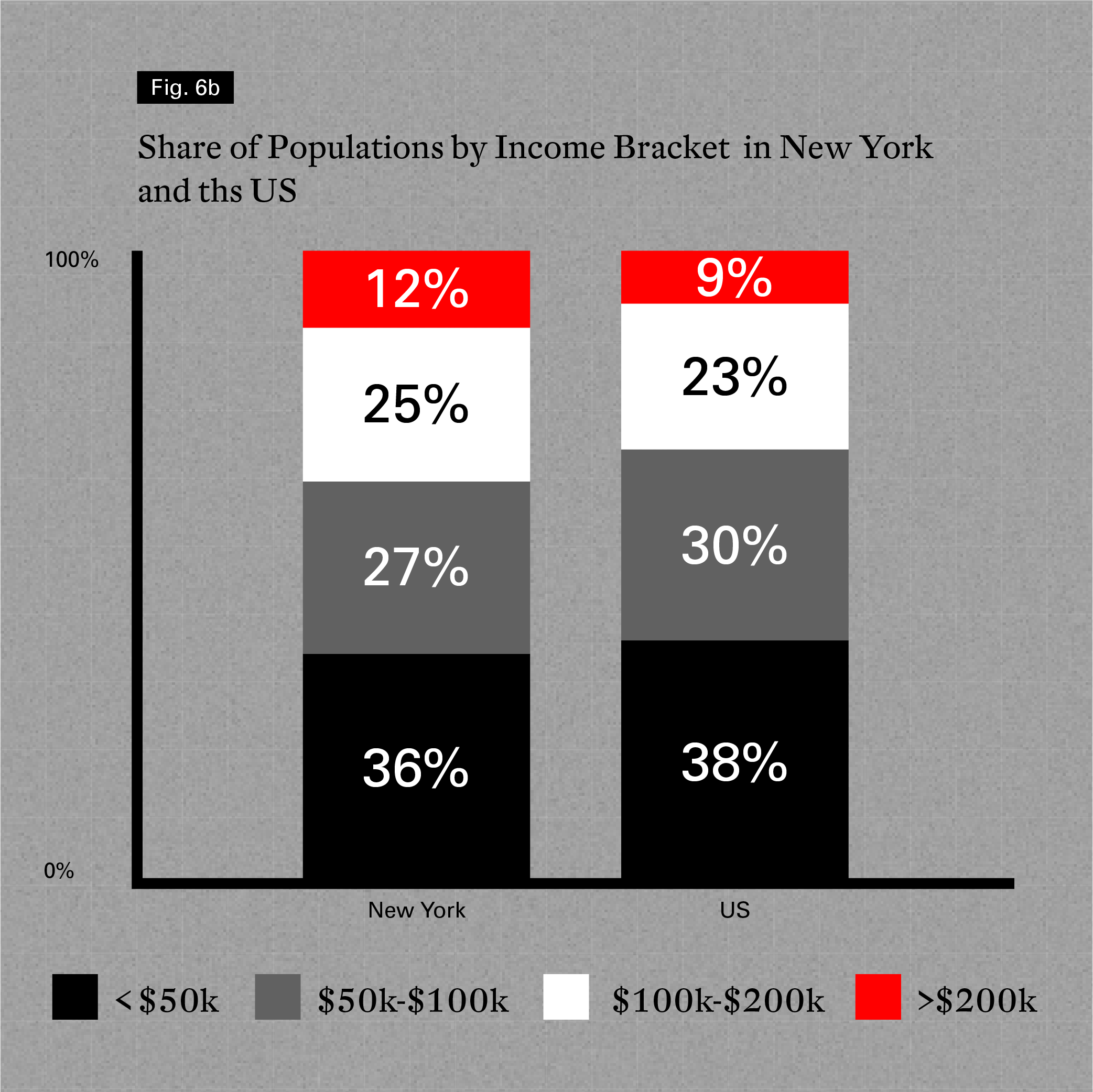

Within the US, 50% of households in New York had wealth over $200,000 in 2019, on par with the US-wide share. However, New York had a higher share in the $500,000 plus segment at 25% (versus 22% for the US as a whole).

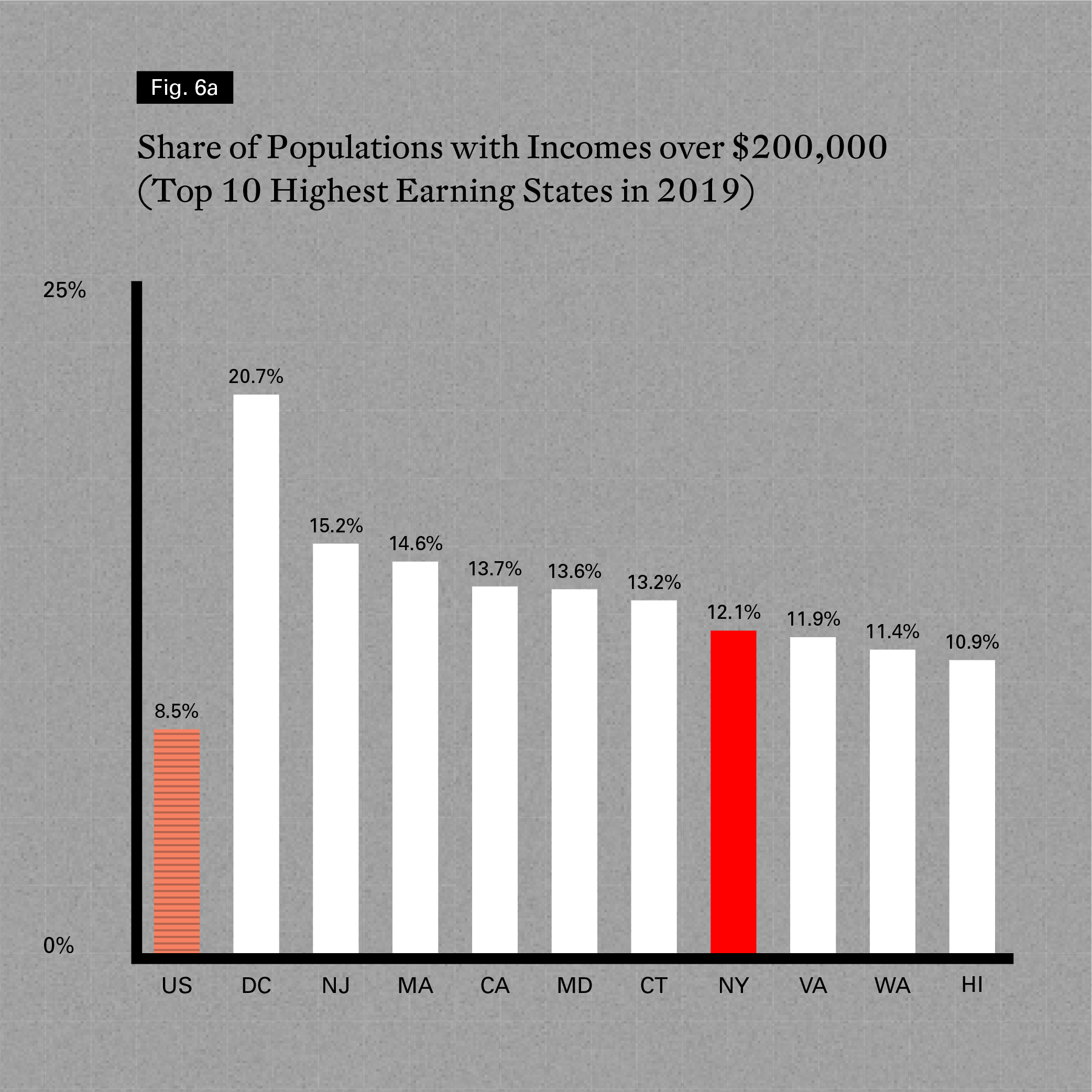

Although wealth is a critical basis for an active art market, income can also indicate the potential to support sales, and New York also has a relatively high share of high current income earners. The average income in New York in 2019 was the seventh highest of all states in the US (at $107,355 compared to the national average of $92,324). It also has a high share of upper-middle income households. In 2019, over 1 million households in New York had incomes in excess of $200,000 (12% of households in the state), the seventh highest share in the US and nearly 4% above the national average.

Figure 6. Share of US Population by Household Income Level

© Arts Economics (2020) with data from the US Census

Research has shown how these wealth dynamics in the New York market have specifically supported a thriving luxury sector. New York was ranked the top luxury city globally, according to Wealth-X, whose rankings incorporate metrics based on the level and growth of city-based wealth, the development of the luxury retail market and other related lifestyle factors. The premium position awarded to New York was based on the fact that its metropolitan area is the largest regional economy in the US and home to more wealthy individuals and billionaires than any other city in the world, as well as scoring highly in terms of luxury lifestyle and infrastructure. It is interesting to note also that billionaire research by Wealth-X also ranked philanthropy as the top interest among global billionaires (51%), while 21% cited art collecting as their key passion14.

More specific research on top art collectors, such as ArtNews’ Top 200 Collectors annual list, has also repeatedly highlighted the importance of the US, and New York specifically, as the key international base for leading collectors. Despite the rapid globalization of art buying over the past two decades, US-based collectors continued to make up close to half of this list in 2020, and those with a permanent or other base in New York account for close to one quarter. This has been a consistent feature of the list since it began in the early 1990s: New York-based collectors made up 21% of the list in 1990 and despite many changes in the market, particularly the growth of Asian wealth and markets, they still accounted for 22% in 2020.

The substantial pool of wealth in the US, and specifically in New York, has provided a strong base for supporting the position of the US as the number one market for art worldwide. The collectors that support the market in New York are made up of its permanent and transient residents, and cover a wide range of different demographics, professional backgrounds, behaviors and views. To try to assess how collectors participate and interact in the gallery sector and art market generally in New York, Arts Economics and Independent distributed a survey to New York collectors in August 202015. The survey was distributed to a database of over 1,000 known collectors who resided permanently or temporarily in New York, with 388 completed responses used in the analysis.

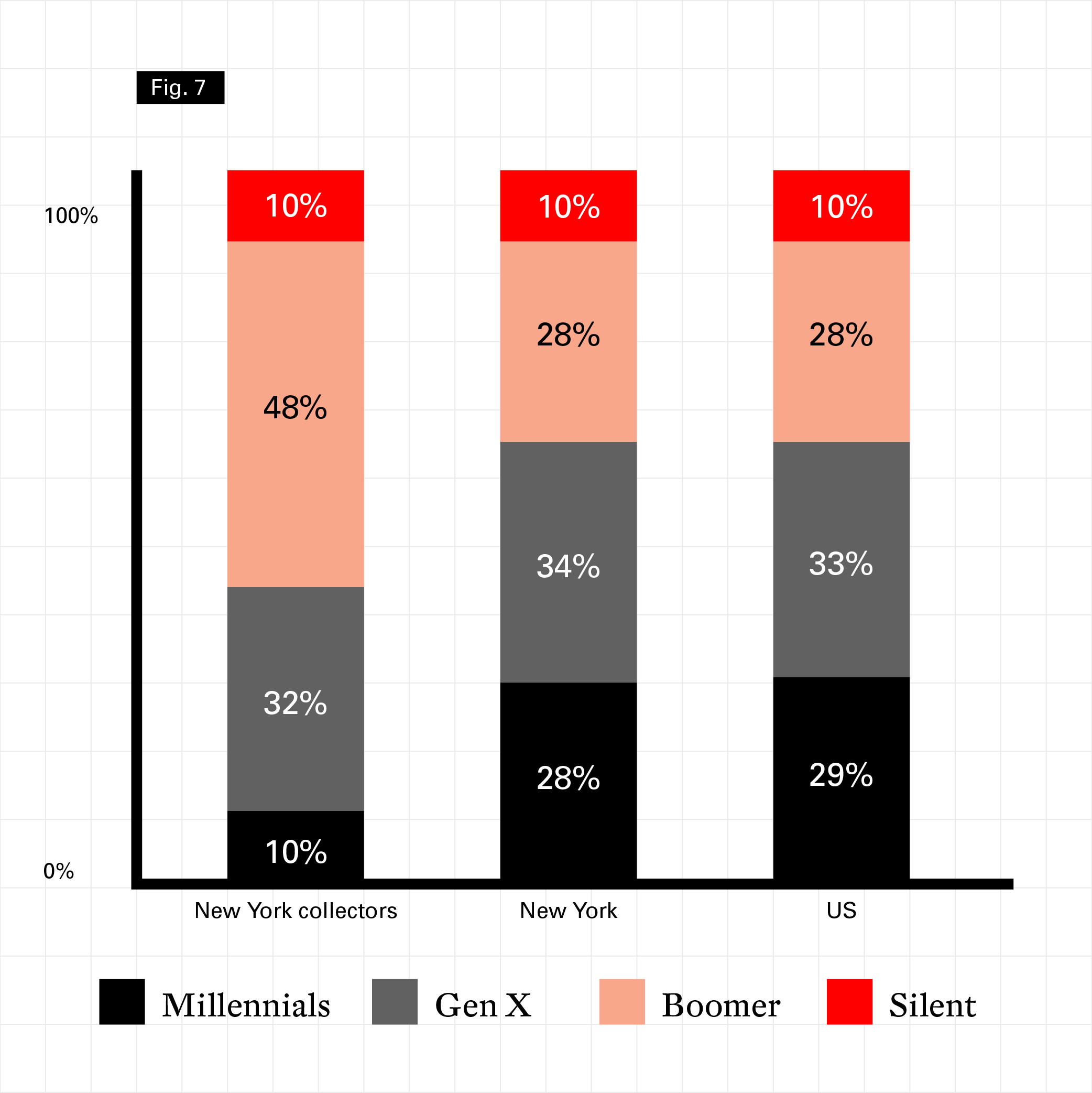

The age breakdown of the sample was skewed to an older demographic than the wider population of New York, and was dominated by boomer (48%) and Gen-X (32%) collectors. This was due to the stratified nature of the sampling, with its distribution to an established sample of collectors16.

Figure 7. Age Profile of Collectors Surveyed versus New York and US Population

© Arts Economics (2020) with data from the US Census 2020. Shares in New York / US refer to the share of the population 23 and over.

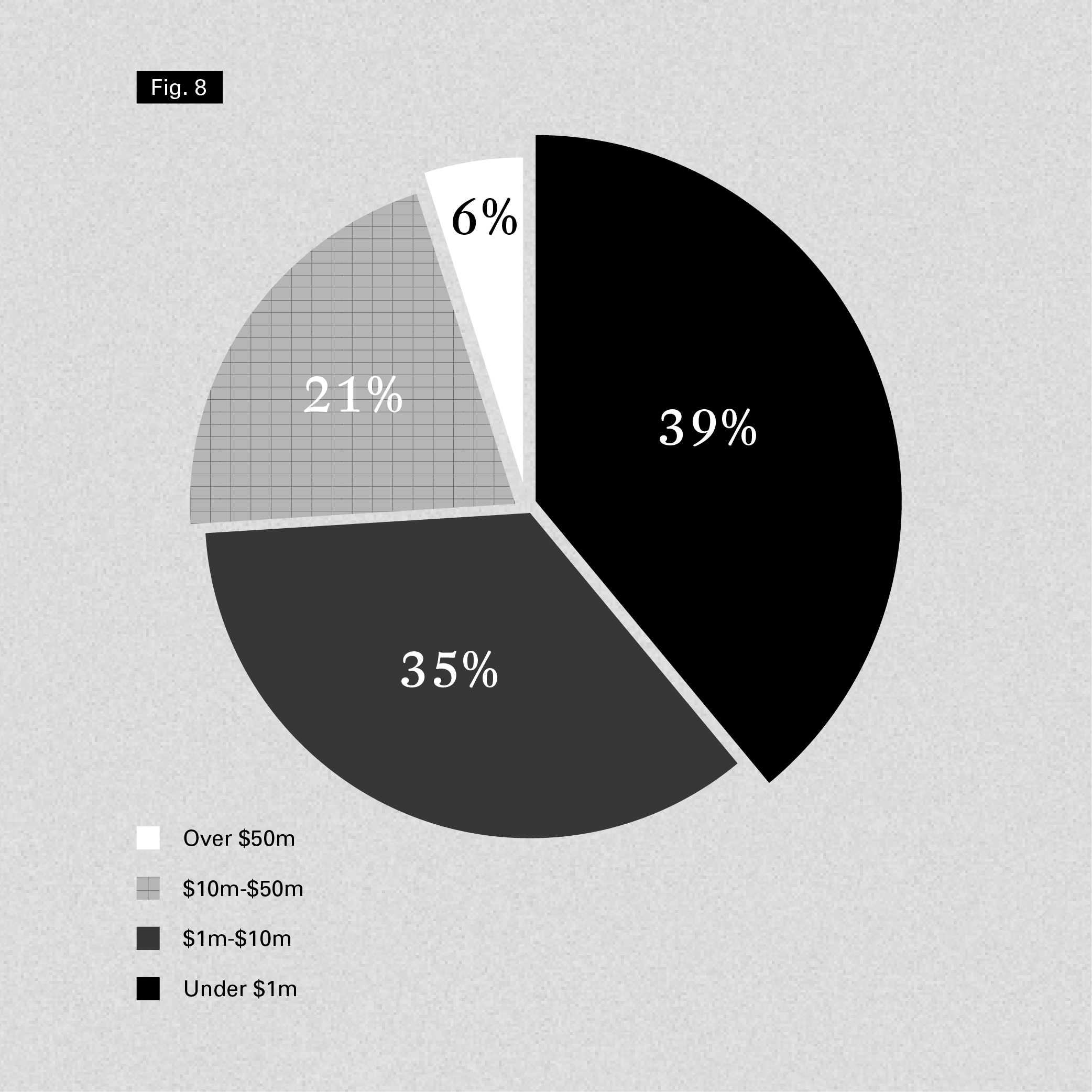

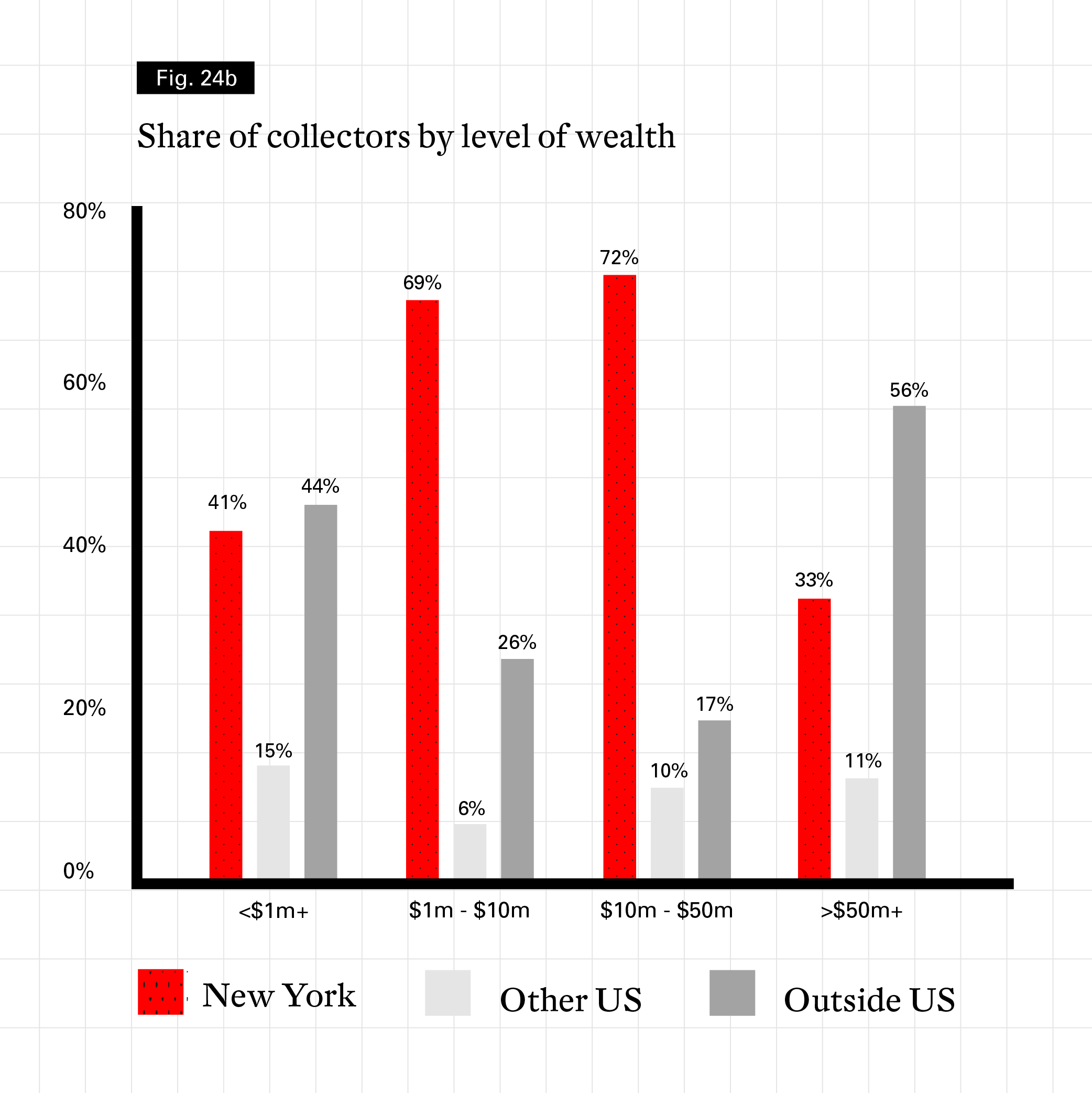

Respondents had varied levels of wealth, but the majority (61%) had personal wealth (excluding any real estate and personal business assets) in excess of $1 million. 27% of respondents had wealth in excess of $10 million, including 6% in the ultra-HNW category of over $50 million. As noted above, the share of the adult population in the US with wealth in excess of $1 million is just less than 8% and those with wealth in excess of $10 million made up less than 0.5% of the population in 2019. Even within New York, 75% of households have wealth of less than $500,000, which shows that this sample of established collectors represents a very wealthy segment of the US and New York population.

Figure 8. Wealth Level of New York Collectors Surveyed

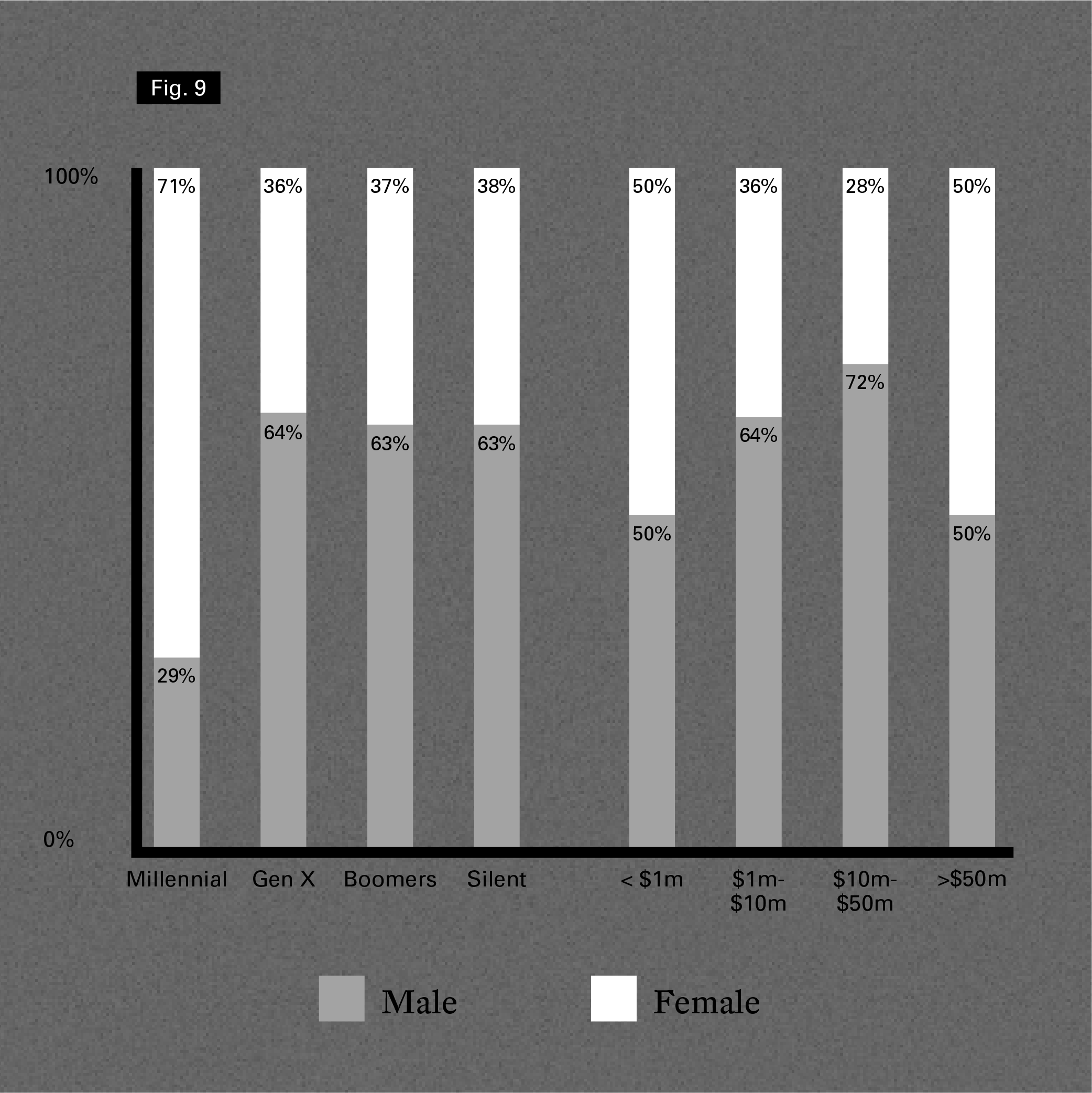

The gender breakdown of the collectors surveyed was 42% female and 58% male17. This is more male dominated than the underlying population of New York and the US as a whole, both of which are 51% female. There was a higher representation of female collectors among younger age segments (71% of millennial collectors were women), and gender was also more balanced in the lowest and very highest wealth brackets (with the segments with wealth below $1 million and above $50 million both 50% female).

Figure 9. Gender of New York Collectors Surveyed by Generation and Wealth Level

© Arts Economics (2020)

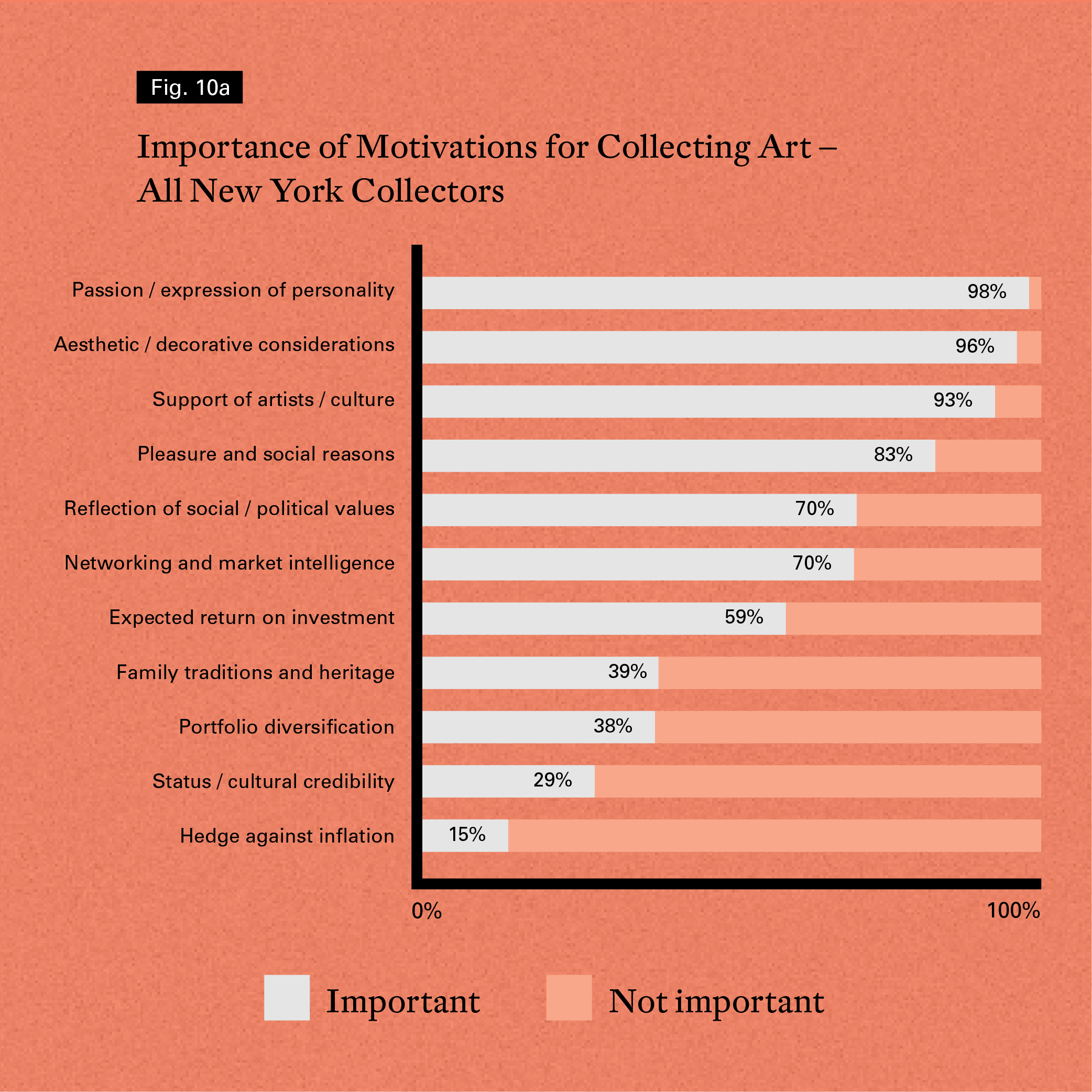

Collectors are driven to purchase art for a variety of reasons. These vary between different individuals as well over different periods for individuals as they build their collections. New York collectors were asked to rank the importance of a number of factors in their decision to purchase works of art. As in previous surveys of other collectors across a variety of different regions, the most highly ranked factors were the following: collecting from a passion for art and as expression of their personality; aesthetic and decorative considerations; and a drive to support artists and culture and other philanthropic motives. These considerations were rated the top three among nearly all age groups and wealth levels in the sample. The only exceptions were millennial collectors, where pleasure and social reasons such as talking about art, spending leisure time and making friendships via the art world ranked their third most important driver, next to passion and aesthetic considerations. Also, for ultra-HNW collectors (with wealth above $50 million), collecting art as a reflection of their social and political values was also the third highest ranked motivation. Their number one driver was supporting artists and culture, followed by a passion for collecting.

These results are mirrored in other surveys of collectors conducted by Arts Economics in collaboration with UBS over recent years, with the same top three motivations reported in research of HNW collectors across seven different global regions in 201918. However, collectors tend to report on non-financial motivations even when there are other drivers evident in their behaviors. For example, the global Arts Economics / UBS collector research revealed that despite not reporting financial motives as their top drivers, many HNW collectors re-sold works rapidly onto the secondary market and kept a high share of works in commercial storage, which, along with other behaviors, indicated that there were some trading or investment-driven aspects to their collecting, particularly among younger respondents.

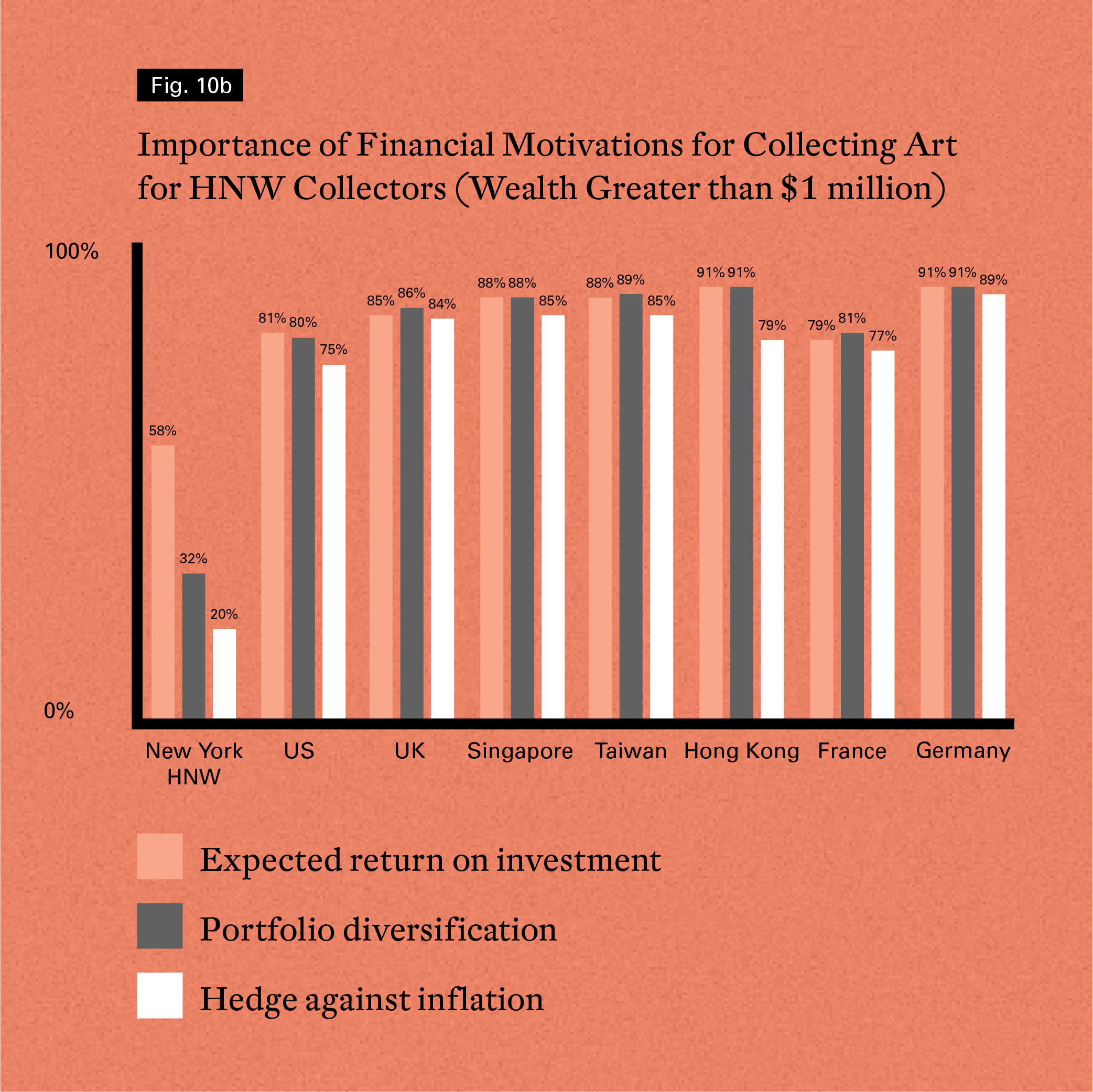

It is noteworthy that in this sample of New York collectors there was significantly different reporting on financial motivations for collecting versus their global counterparts. Although investment-related considerations were among the lowest rated of the selection offered, over 80% of HNW collectors in the seven other external regions studied rated the expected return on investment, portfolio diversification and using art as a hedge for inflation as important considerations. While a majority (59%) of New York collectors felt the expected return on investment was important (with 12% considering it very or extremely important), only a minority of collectors rated the potential for portfolio diversification as important, and art as a hedge against inflation was the lowest rated of all (important only for 15% of the entire sample, 20% for HNW collectors from New York with wealth over $1 million, and 30% for ultra-HNW collectors with wealth over $50 million). These results imply that New York collectors are, or perceive themselves as, significantly less investment driven than some of their global counterparts.

Also, while the importance of maintaining family collections over time was rated highly in other regions, particularly in countries such as France and Germany, legacy was a less important motivator for New York collectors, with only 39% rating it as important in this survey. This may be due to a variety of reasons, including differences in fiscal incentives for maintaining and transferring collections within and across families (see Chapter 5) as well as the more contemporary focus of the New York market and the collectors within it.

Finally, while status, cultural credibility and owning art as a signal of personal wealth and success was a driver for the majority of HNW collectors in other regions (with over 80% rating these important across seven global regions in 2019, including over 90% in some Asian markets such as Hong Kong and Taiwan), this was not an important motivator for most New York collectors, with 71% of respondents reporting it as not important at all.

Figure 10. New York Collector Motivations for Collecting Art

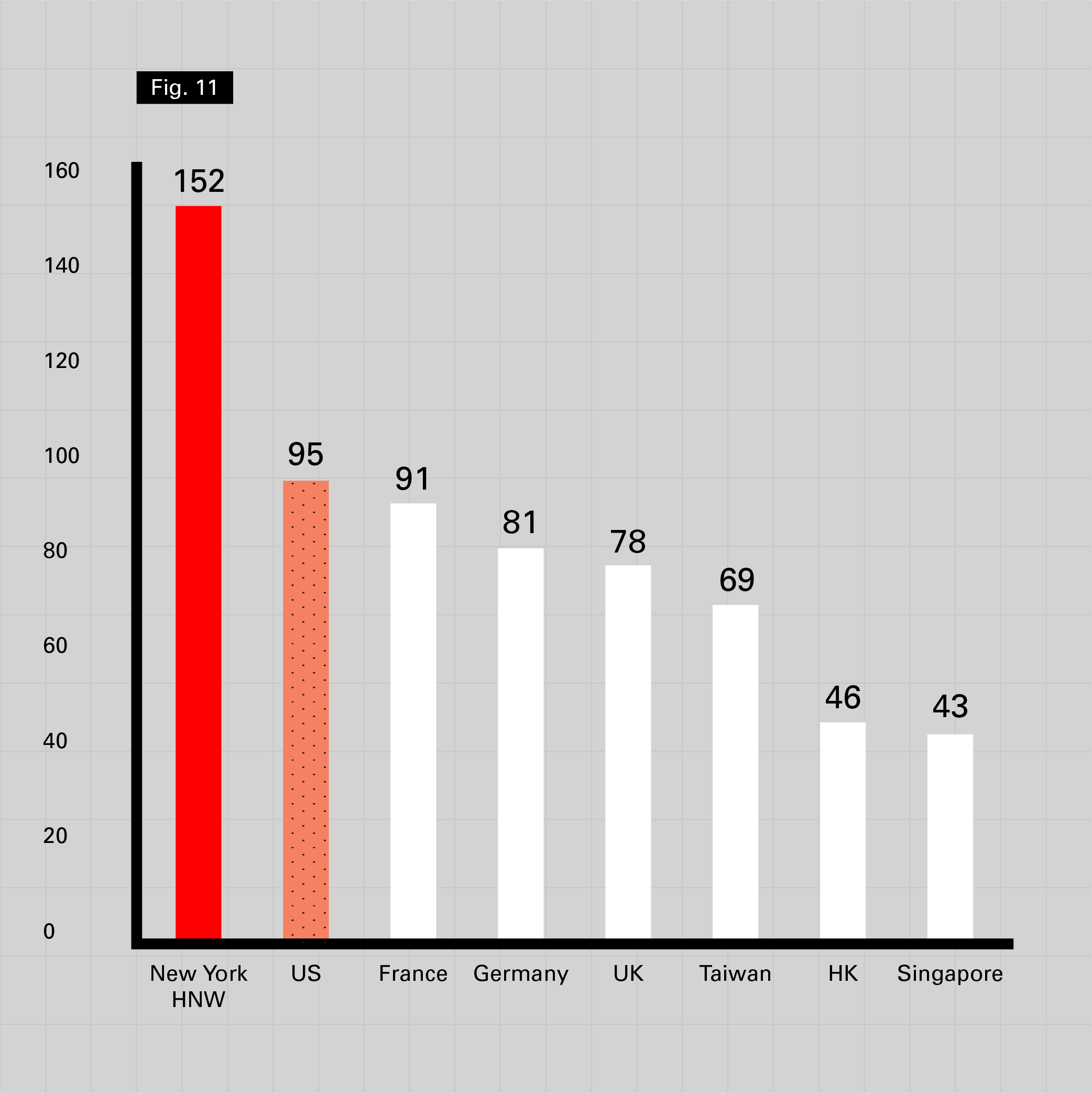

New York collectors have large collections of art. A majority (72%) of the collectors surveyed had more than 50 works in their collections, with just over half having more than 100 works. The average collection size across all New York collectors surveyed was 146 works. Figure 11 shows that HNW New York collectors with wealth in excess of $1 million had a slightly higher average at 152 works, and this was considerably higher than the averages of other HNW collectors surveyed in different international regions in 2019 by Arts Economics and UBS. The differences may be due in part to the level of establishment of the collectors surveyed in New York as well as their higher age demographic19. The size of collections held by New York collectors was positively correlated with age: millennials averaged 45 works, Gen X collectors had 115, boomers 168, and those collectors from the Silent generation had over 200 works on average. Collection size also increased with levels of wealth, from an average of 90 works for those with wealth less than $1 million to collections twice that size (185 works) for those over $10 million.

Figure 11. Size of HNW Collectors’ Collections (Number of Works)

© Arts Economics (2020)

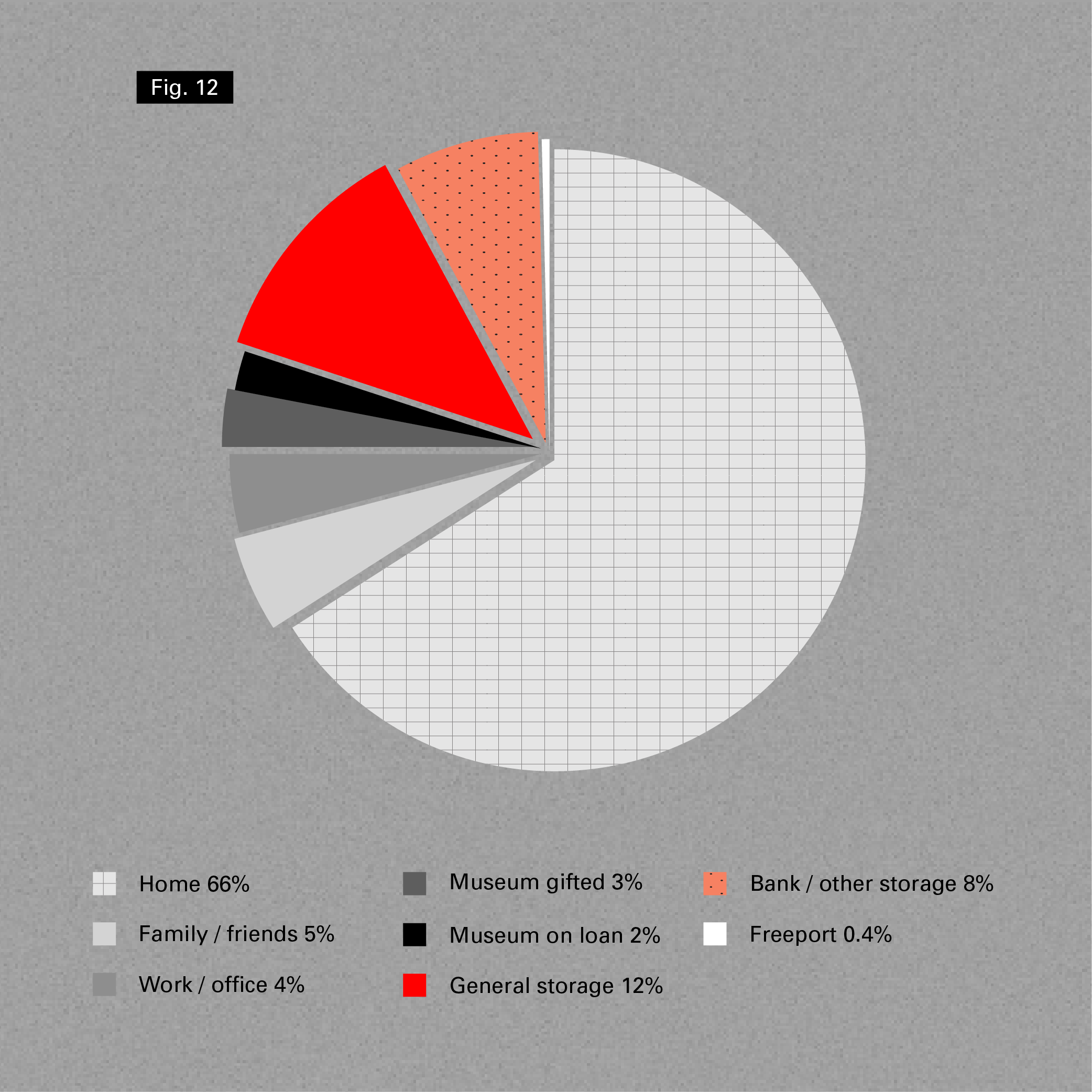

Given their large collection sizes, exhibition space and storage are important issues for many New York collectors. However, despite owning a large number of art works, collectors held or exhibited the majority of works from their collections at home, work or in the homes of friends (75% of their art works on average). This again reflects the less investment-driven motivations of many New York collectors, who display and exhibit the works that they purchase for personal enjoyment or other non-pecuniary motivations. On average, collectors had 5% of their artworks stored in museums, including 3% that they had gifted to the museum20. The remaining 20% of collections were in either general or specialized storage.

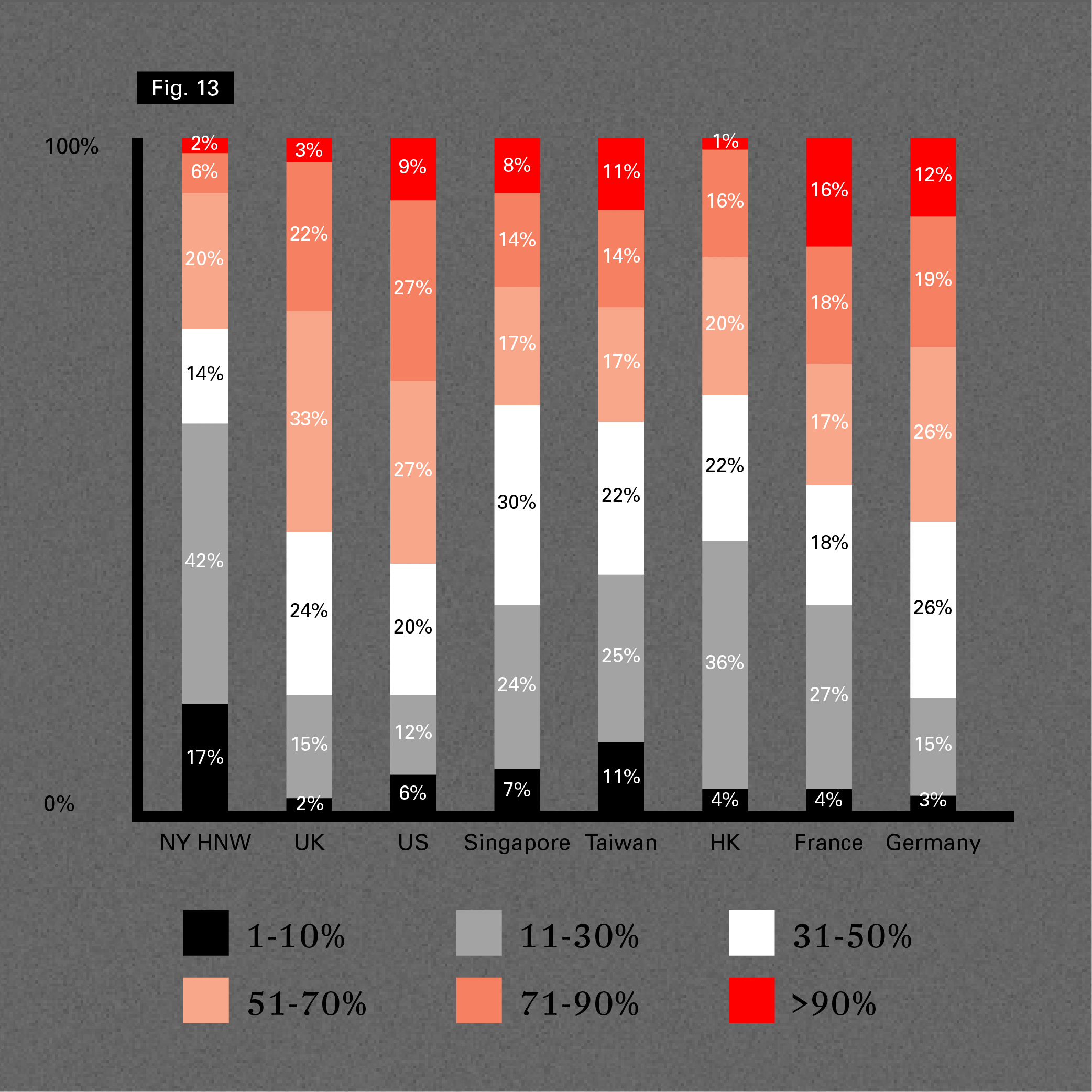

Figure 12. Location of Exhibition or Storage of New York Art Collections

For those collectors that had works in storage, most only kept a relatively small portion of the value of their works stored out of view, with the majority keeping less than 30% of their aggregate collection by value in commercial storage. Considering HNW New York collectors that had works in storage, only 28% had half or more of the value of their collections stored, which is significantly less than indicated in other surveys of HNW collectors elsewhere. However, although they stored less by value, they did tend to store works for longer. Just 11% of New York collectors put works in storage for less than one year, while 27% had parts of their collection stored for one to three years. 44% reported that they had works in storage for longer than five years (versus an average of just 12% in surveys of HNW collectors in other regions).

Figure 13. Share of Collectors by Share of the Value of their Collection in Storage

© Arts Economics (2020)

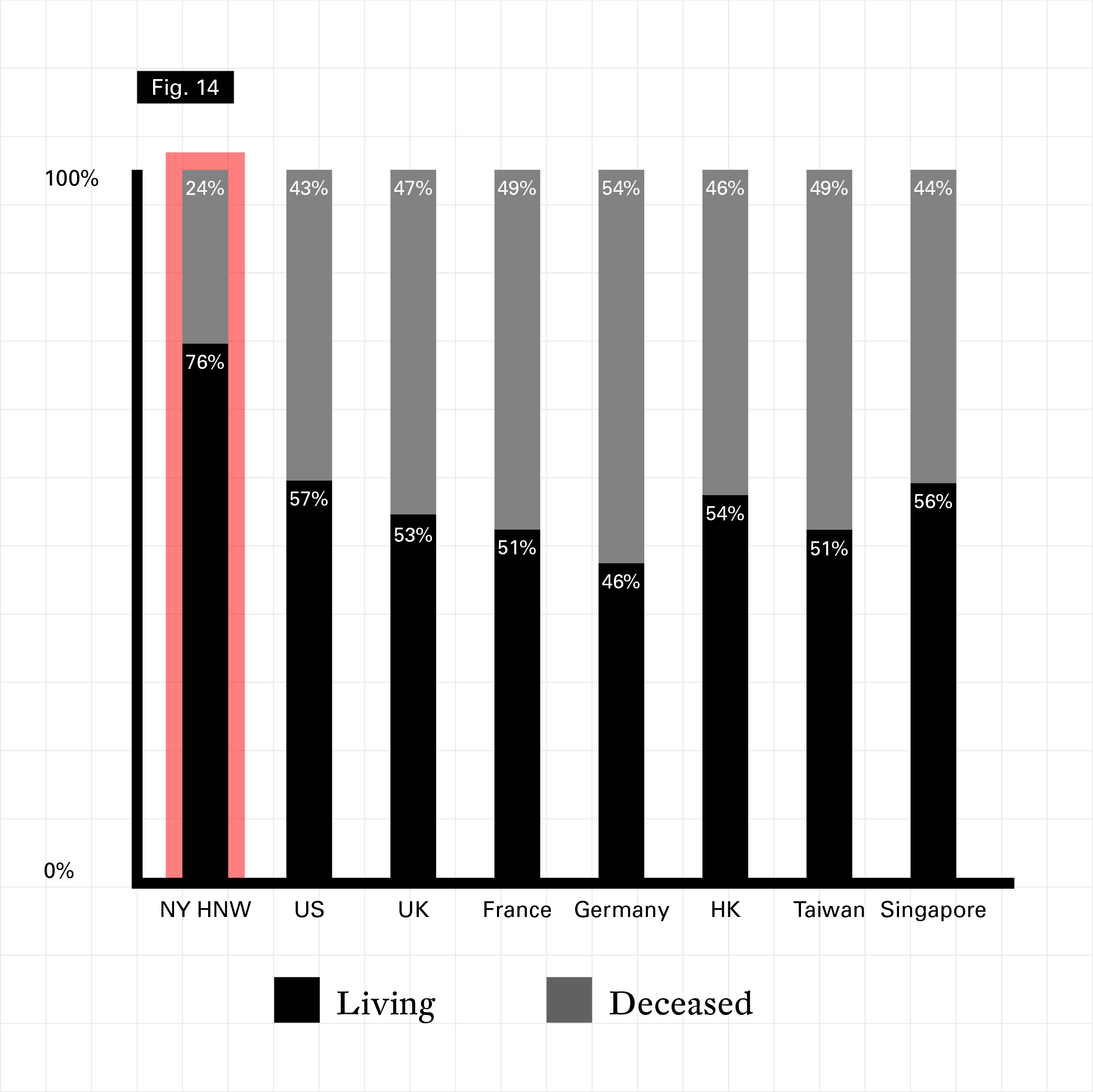

Besides having larger collections, the content of New York collections also revealed differences between collectors. New York is a key center of sales of contemporary art and this was reflected in the works contained in the collections of its residents. Across all New York collectors surveyed, the majority (80%) of works they had purchased for their collections were by living artists, with just 20% by deceased artists. Gen X collectors had the largest share of works by living artists (87%), while Silent generation collectors had the lowest share, although still a majority at 67%. Millennials were on par with boomers at around 78%. There was a tendency for wealthier collectors to have a slightly lower share of living artists’ works: these made up 89% of the works in the collections of those with wealth less than $1 million, versus 76% for HNW collectors. Even at this level, however, the share of works by living artists in New York collectors’ collections was significantly above HNW collectors in other regional markets, including the aggregate for the US which was 57%.

Figure 14. Share of Works Purchased by HNW Collectors by Living versus Deceased Artists

© Arts Economics (2020)

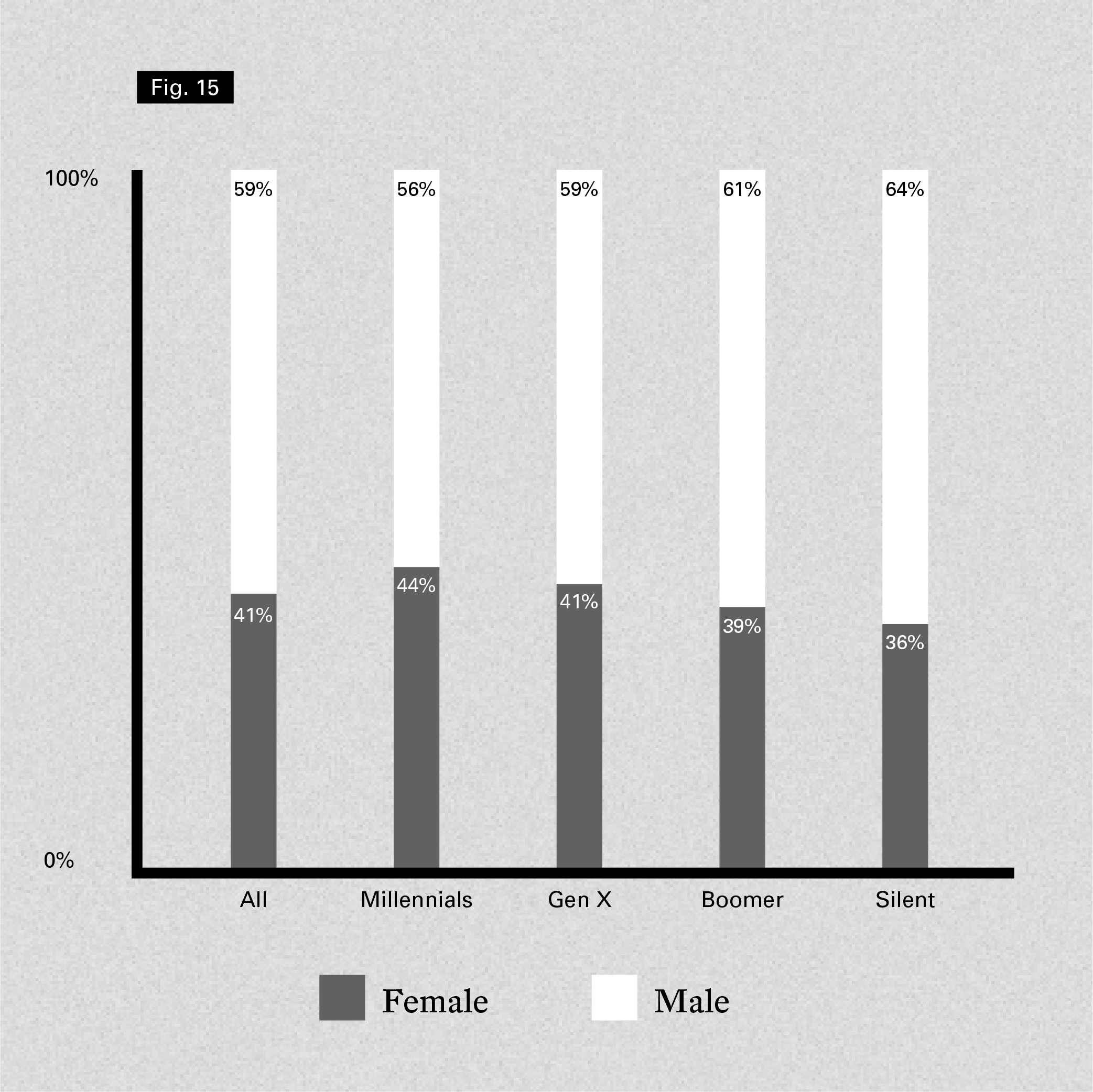

Regarding the gender of artists included in collections, New York collectors were more on par with their counterparts from other countries, with women representing a minority of 41% of the total works on average. Millennials tended to have slightly more works by female artists than their older counterparts, but across all generations, female artists were a minority share. This was also the case for female collectors, whose collections contained 43% female artists’ works versus 38% for male collectors. The only gender balanced collections were those of millennial female collectors with a share of 50% female artists’ works.

When New York collectors were asked about their key concerns regarding the market in 2020, a majority (80%) of respondents felt that gender disparities and the position of female artists in the art market was a concern. However, it was not one of the top rated concerns, with just less than half (46%) of collectors being very or extremely worried at present about these issues. When surveyed in 2020, Arts Economics found that a slightly higher 58% of US-based HNW collectors reported being very or extremely concerned about gender inequity. As in the case of New York respondents, this was lower ranked among the list of concerns offered to respondents. The lower share in the New York sample in 2020 could relate to the dominance of more immediate concerns relating to the COVID-19 crisis and other issues that dominated at the time of the survey, with the closure of galleries ranked as the greatest concern overall. Gender disparities were also a greater concern for millennial collectors (63% were very or extremely concerned), however, this was influenced by the fact there was a majority of female collectors in this segment. Female collectors of all ages tended to be more concerned about gender disparities (62% very or extremely concerned) versus their male counterparts (34%).

Figure 15. Share of Works Purchased by New York Collectors by Artist’s Gender

© Arts Economics (2020)

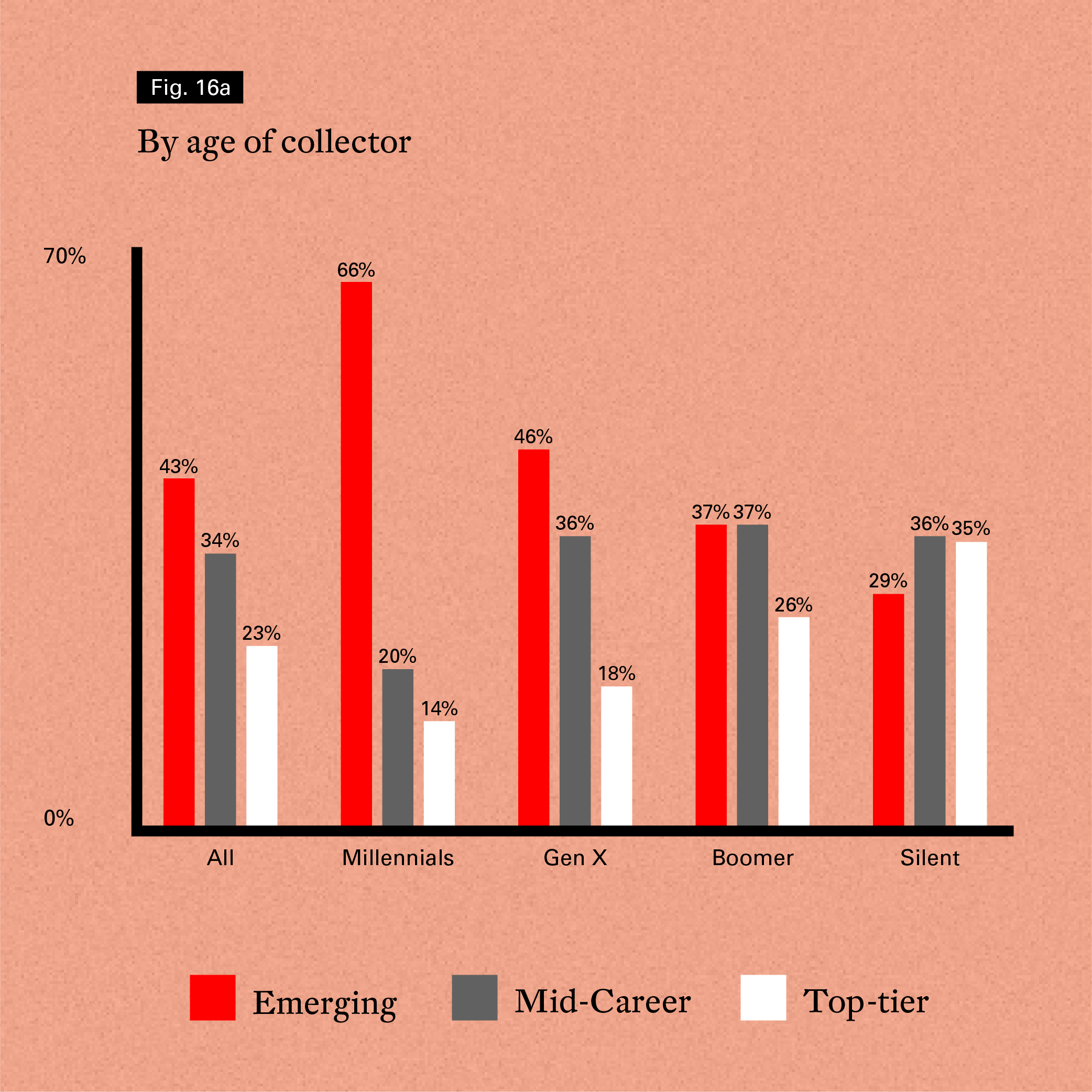

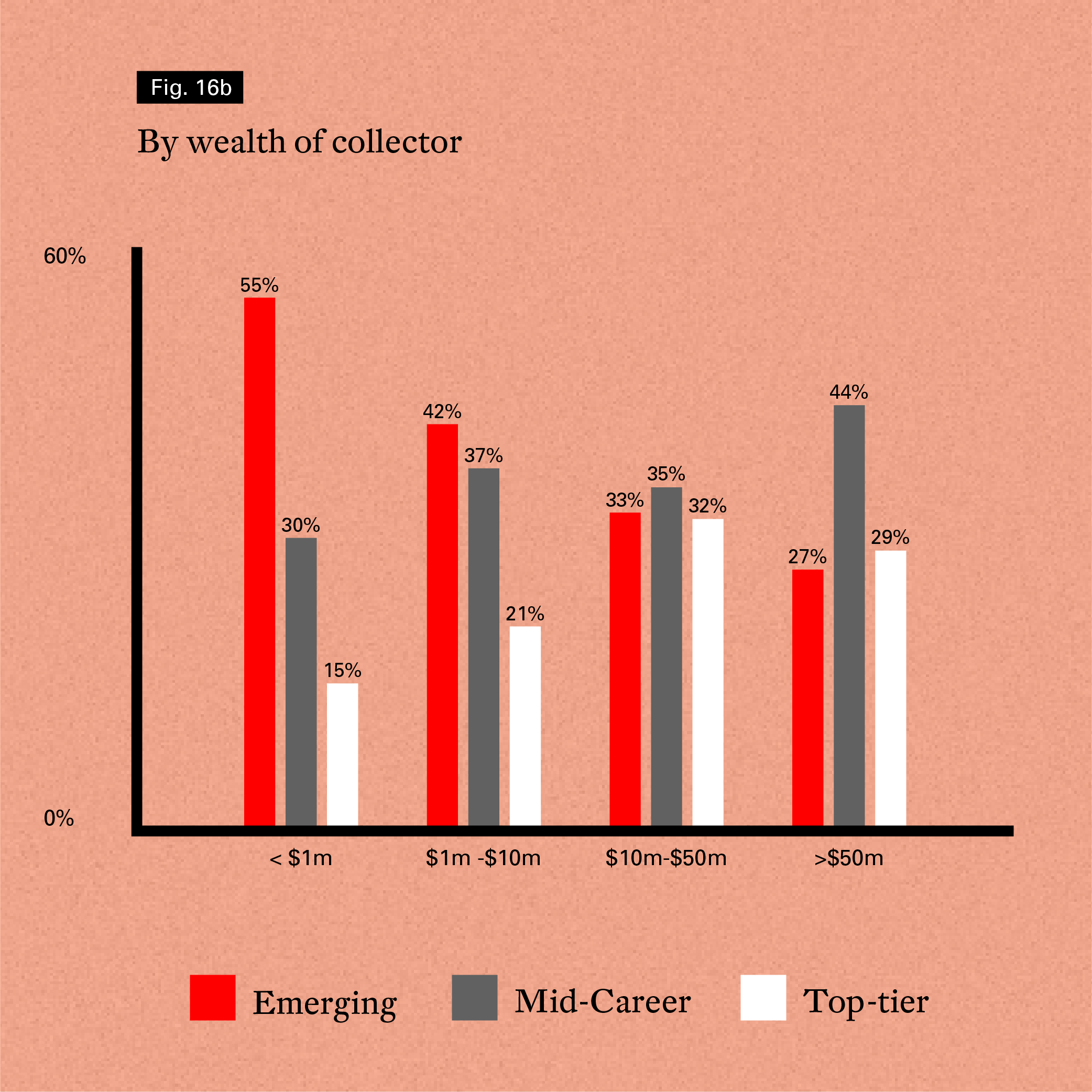

Although New York is the central market for the sales of the highest priced works of art, New York collectors revealed varied interests in artists at different levels and career stages, and a strong willingness to collect untested and emerging artists. Across all collectors, the largest segment collected was works by emerging artists (43%), who were defined as artists developing in their careers, including those who had been showing in galleries and museums for less than a decade. Just over one third of the works in the collections of New York collectors were works by mid-career artists, defined here as those artists with a solid reputation in galleries and museums, showing for more than ten years and with an established name, but not yet considered top-tier. The remaining 23% were those by top-tier artists, with a strong and well-established secondary market in the auction and / or gallery sector and that regularly had works selling for prices in excess of $100,000.

As might be expected, the share of top-tier artists in collections increased with the age of the collector, possibly reflecting their longevity as collectors, the progression of artists in their collection and the accumulation of wealth and rising incomes over the collectors’ lifecycle which may have altered the budgets they had available for purchasing. The share of top-tier artists also increased with levels of wealth (up to a ceiling of $10 million), although even at the highest wealth levels, New York collectors still had relatively diversified collections, with mid-career artists tending to be the largest segment overall.

Across all collectors, only 18% of respondents reported that half or more of the works in their collections were by top-tier artists. Millennial New York collectors had by far the highest share of works by emerging artists and around half of these younger collectors had 5% or less works by top-tier artists (including 35% who had none). Millennial collectors were also the most likely to be concerned about equality and poverty issues in the art market and the rise of top-tier and superstar artists over others. When asked about their concerns in 2020, around half of collectors overall were extremely or very concerned about these issues, and this share was higher (at 75%) for millennial collectors.

Figure 16. Share of Works Purchased by New York Collectors by Artist’s Career Stage

© Arts Economics (2020)

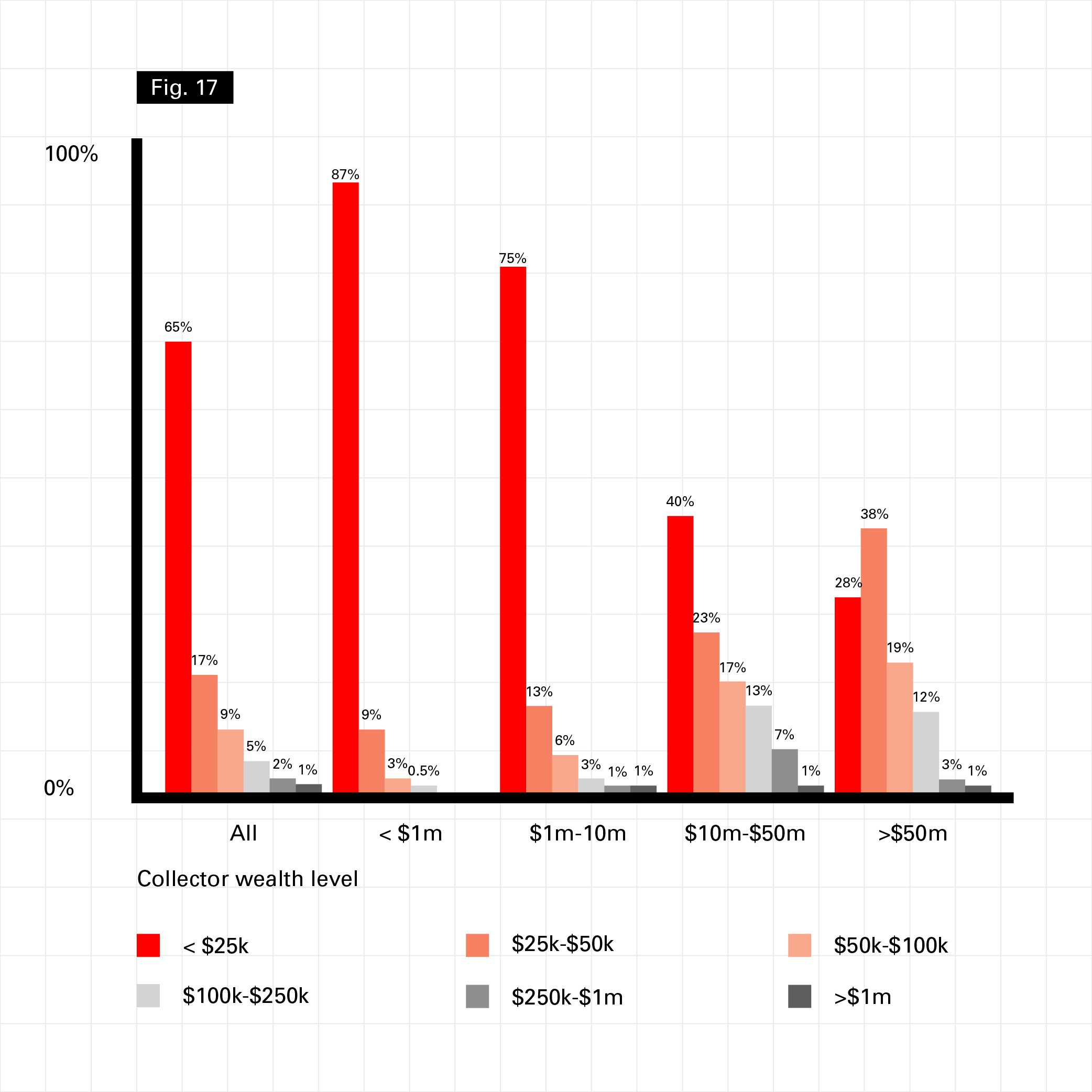

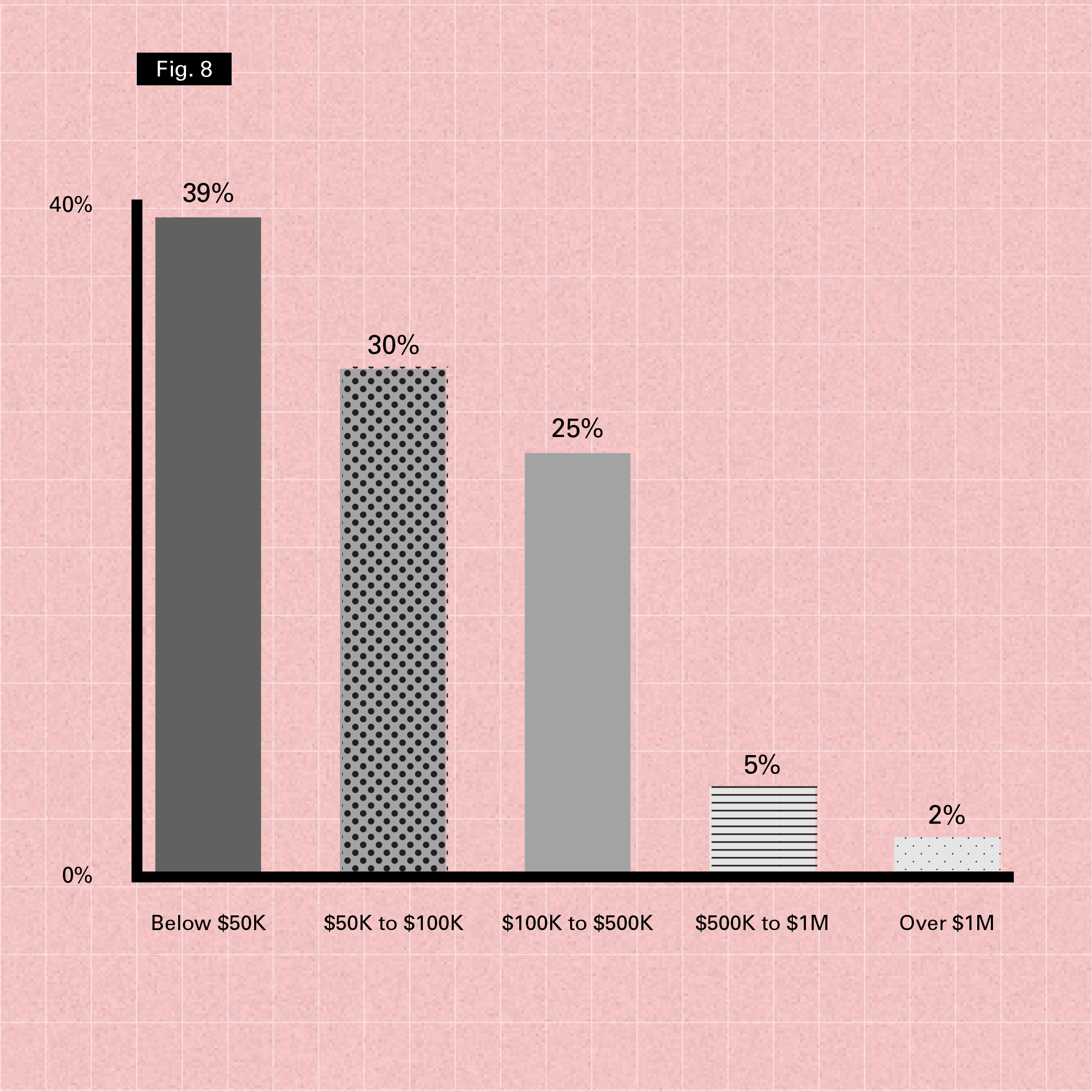

Despite many of their collections being valued at multi-million dollar levels, the majority (82%) of works owned by collectors in New York had been purchased at prices less than $50,000. The share of works purchased at higher price levels increased as the collector’s wealth increased, but even at the level of ultra-HNW collectors (with wealth over $50 million), 66% of the works currently in their collections had originally been bought at prices below $50,000.

Figure 17. Share of Works Purchased by New York Collectors by Original Purchase Price

© Arts Economics (2020)

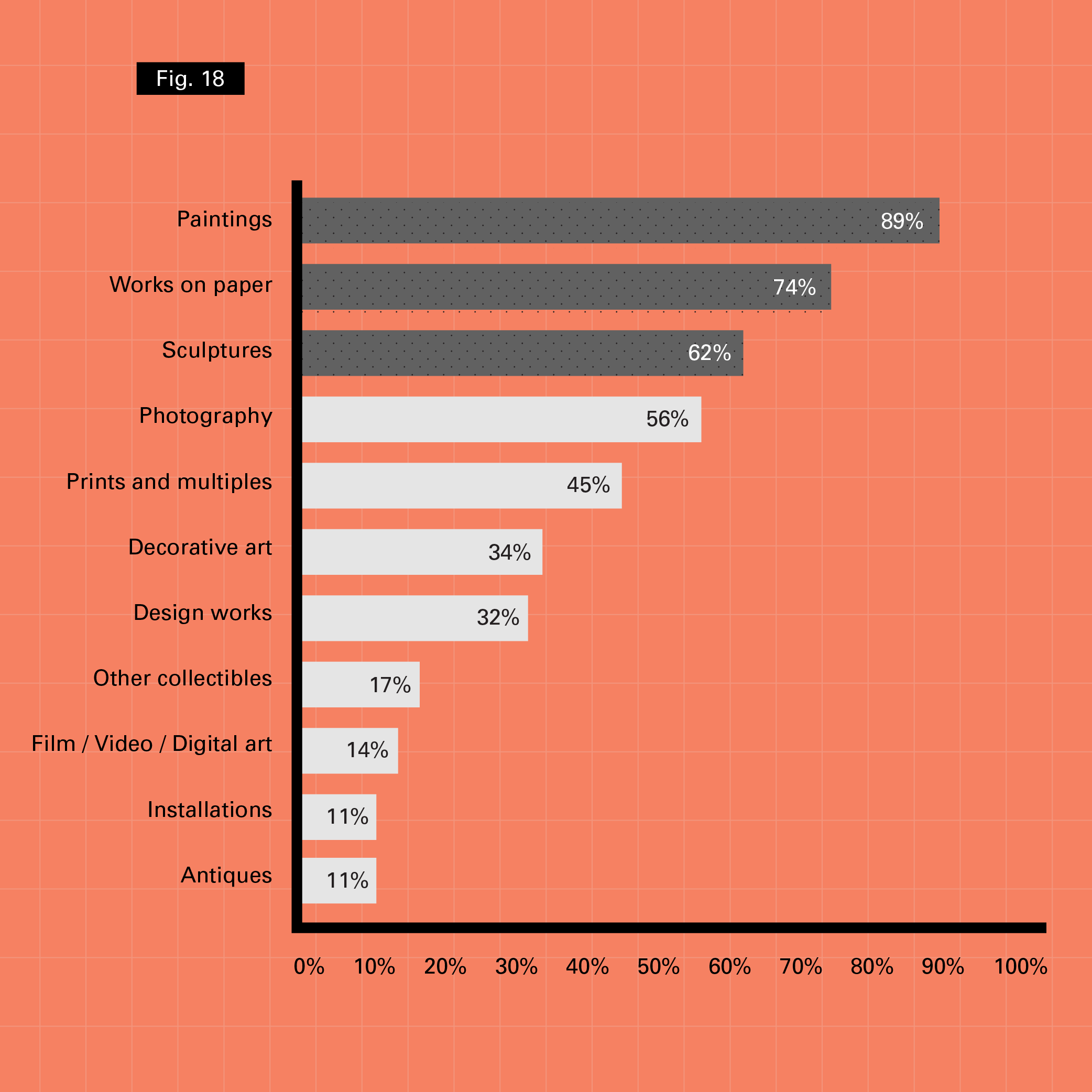

An analysis of their expenditure on art and collectibles over the last two years shows that New York collectors have been primarily focused on fine art. Paintings were the most commonly purchased art form across all collectors, as well as for each generation and wealth level. Works on paper and sculptures were also popular, as well as photography (particularly with millennial collectors). Unlike previous research on global HNW collectors in different regions which showed a high rate of cross-collecting outside of fine art, New York collectors were more focused, with only a minority of the collectors surveyed having purchased antiques and collectibles, and around one third having bought design works or decorative art. Film, video and digital artworks were purchased by 14% of respondents in the last two years. Although a newer medium, this segment had a higher share of collecting interest in older generations (16% for collectors from the Silent generation versus 8% for millennial New Yorkers).

Figure 18. New York Collectors’ Purchases by Art Form in the Last Two Years

© Arts Economics (2020)

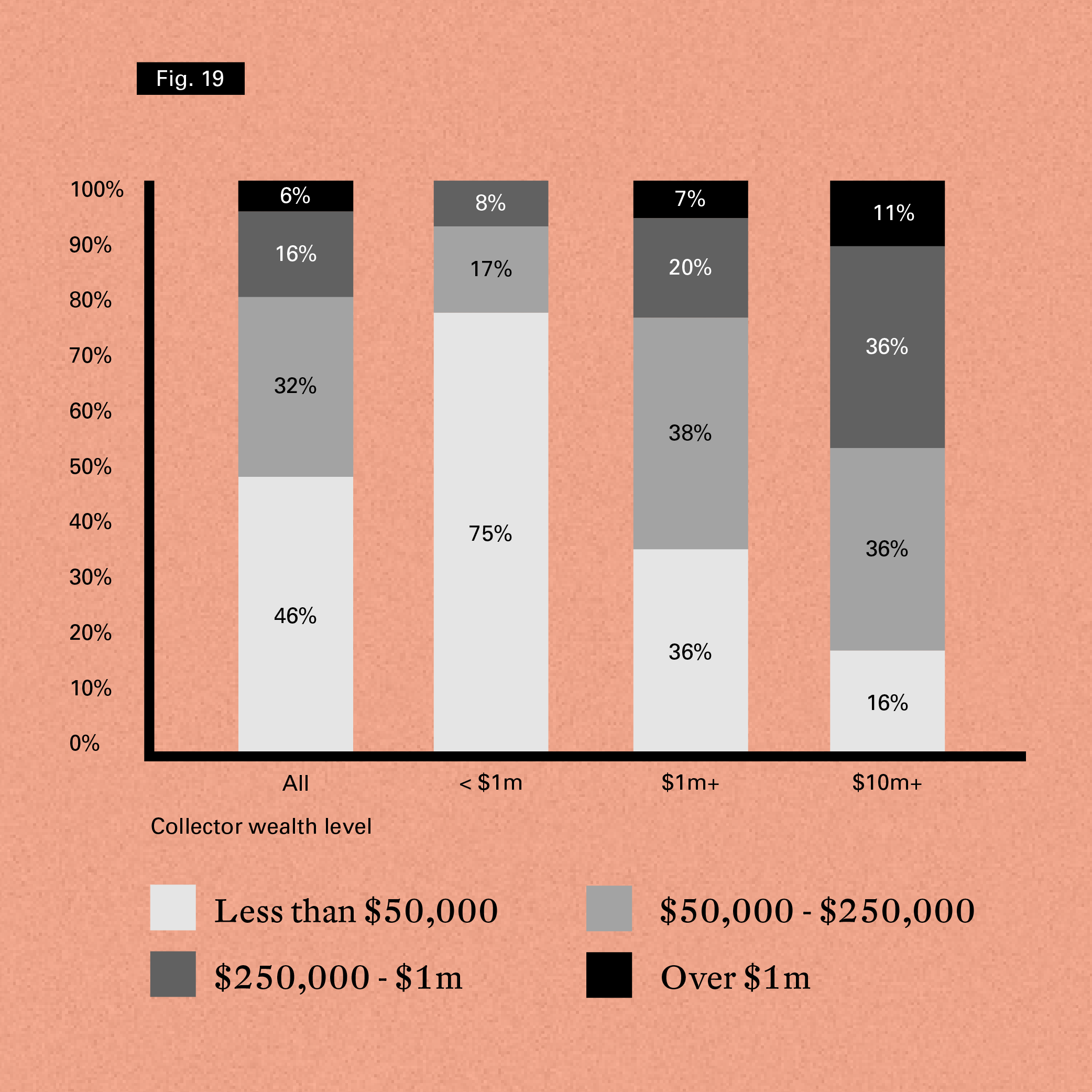

Collectors spent an average of $759,000 per annum on art works for their collections per year over the last three years, although this ranged considerably by age and wealth level. The average annual expenditure for millennial collectors was just over $45,500 versus around $600,000 for Gen X and boomer collectors. Collectors from the Silent generation had a much higher reported average of $3.4 million per annum.

As would be expected, expenditure levels tended to rise with levels of wealth. While the majority (75%) of collectors with wealth less than $1 million spent less than $50,000 per year on works of art, this was just 16% for those with wealth greater than $10 million. This higher wealth segment showed the highest rate of annual spending at the $1 million plus level (11%).

Figure 19. Share of Collectors Typical Total Annual Spending by New York Wealth Level

© Arts Economics (2020)

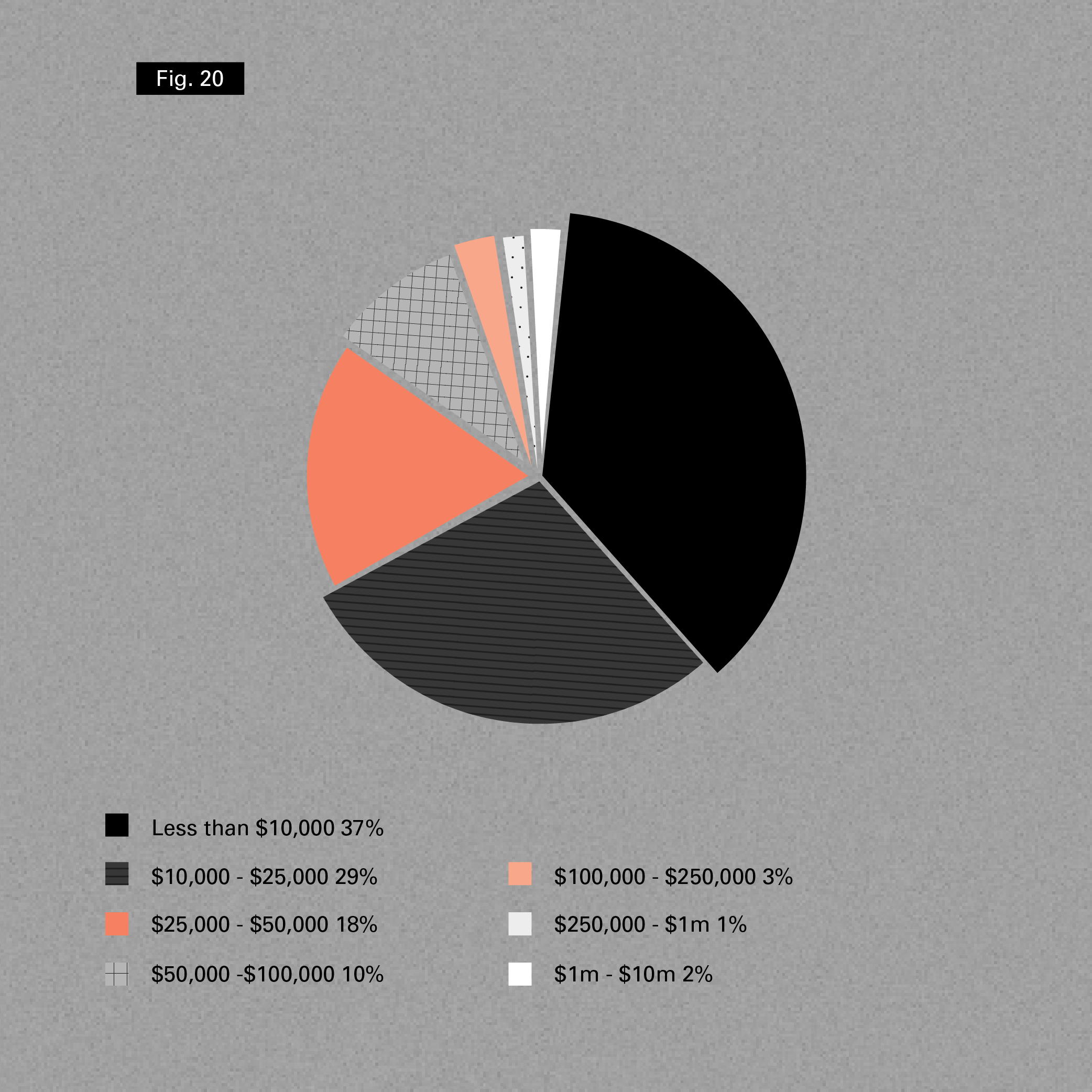

Despite high levels of annual spending, most collectors (84%) reported that they most often transacted at prices less than $50,000 for individual works, including 78% of the HNW New York collectors. This indicates the range and breadth of purchasing activity by collectors at different price levels in New York, as well as potentially high levels of activity for some, given their annual average expenditure. This share is also considerably higher than the ranges reported in previous surveys of HNW collectors in other regions in 2019, with those most commonly spending at $50,000 or less, ranging from 23% in the UK to 39% in France and the US as a whole. There was also a smaller share of respondents in the sample of New York collectors transacting most regularly at prices in excess of $1 million at 2% versus higher averages of 11% in Hong Kong, 24% in the UK and up to 29% in the US as a whole. Figure 20 shows that, despite it being a center for the sale of the highest priced works in the world, collectors in New York support the market through purchasing at a wide range of levels, including a large volume of works at the lower priced ends of the market.

Figure 20. Most Common Price Range used by New York Collectors for Purchasing Works of Art

© Arts Economics (2020)

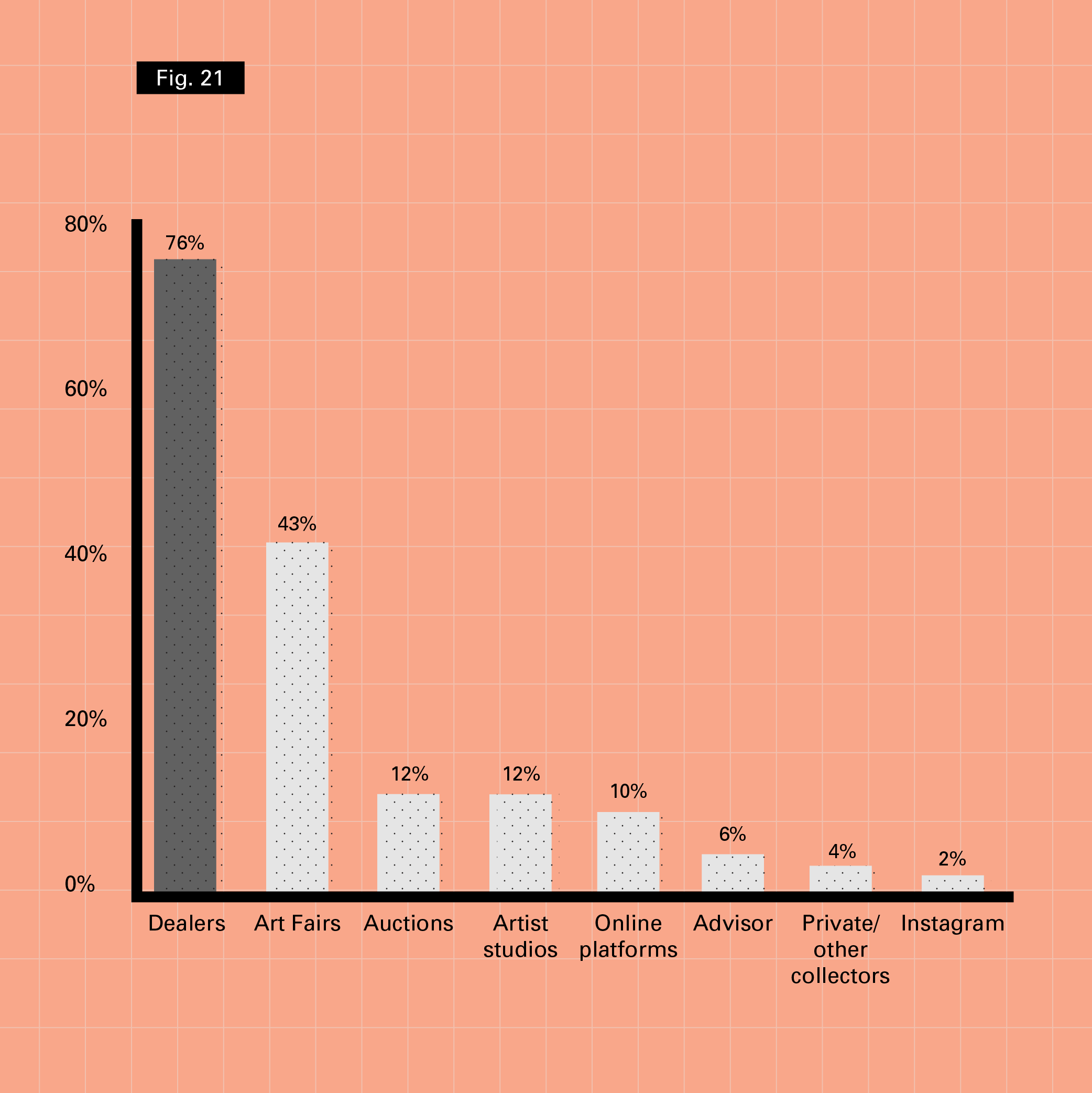

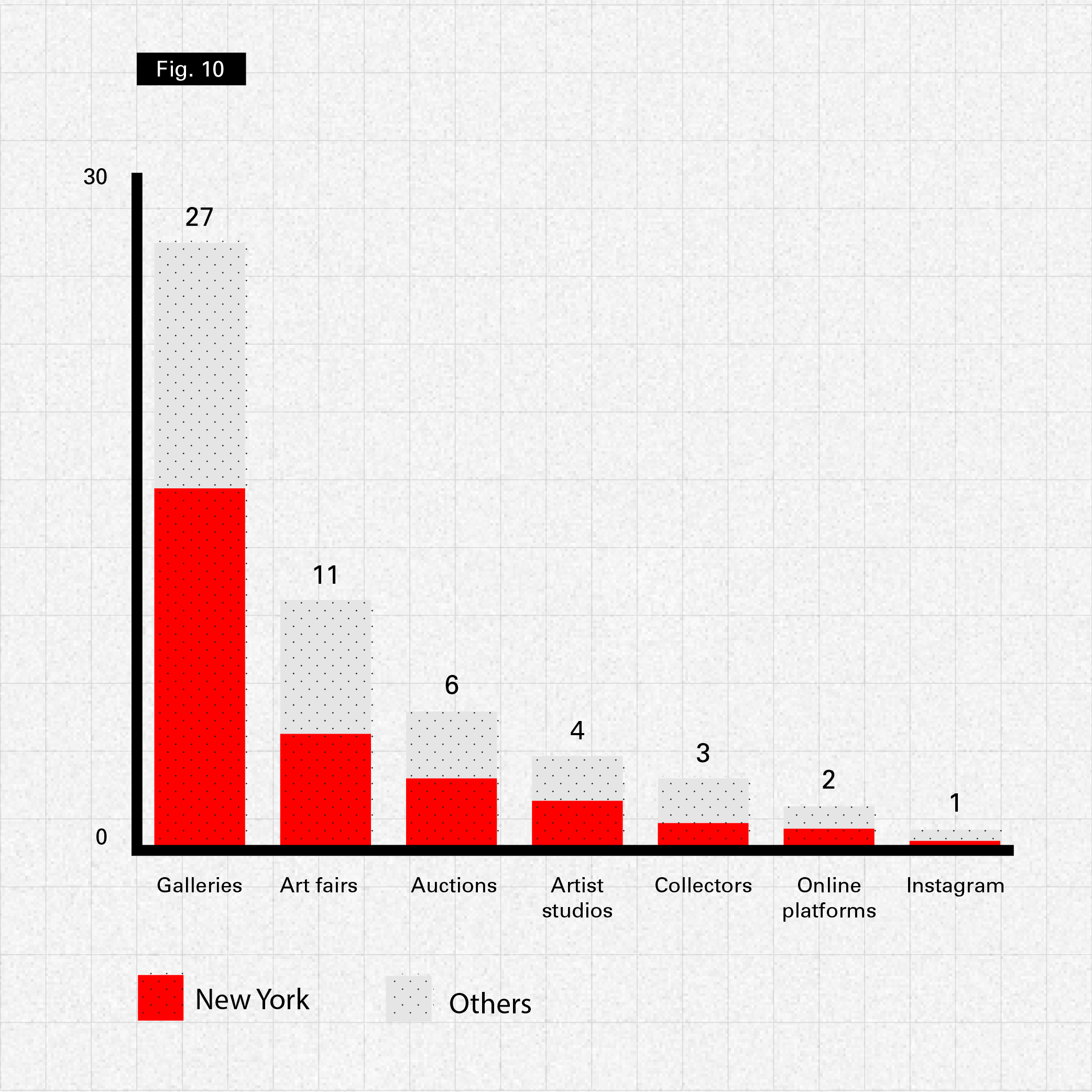

New York collectors used a variety of different sales channels to purchase art, with many regularly using multiple channels. By far the most frequently used option by a considerable margin by New York collectors was buying through galleries and dealers. All of the respondents surveyed had used dealers to purchase art at some point, with 76% using them always or often.

Despite the size and importance of the New York auction market, auctions, on the other hand, were used less by New York collector in this sample. While around 80% had used them to purchase art, only 12% reported using them always or often (versus half or more of the HNW collectors in other regions). This finding was consistent across generations, with a slightly lower level of use for New York’s millennial collectors (only 56% of whom had bought at auction).

Similarly, although 82% of New York collectors reported having purchased from artists’ studios and 74% used online channels, these were both only used frequently by a minority of collectors. The least used of all to purchase art directly was Instagram, with only 27% of collectors in New York having ever purchased a work directly from the platform (that is, had bought an artwork found on Instagram and purchased directly or through a link on Instagram to an artist, gallery or other seller). While other surveys have found a distinct generational component to the prevalence of use of online channels and social media, this was not the case in this survey, and they were infrequently used across all age groups.

Figure 21. Frequency of Use of Sales Channels (Share of New York Collectors Using Channel Often or Always)

© Arts Economics (2020)

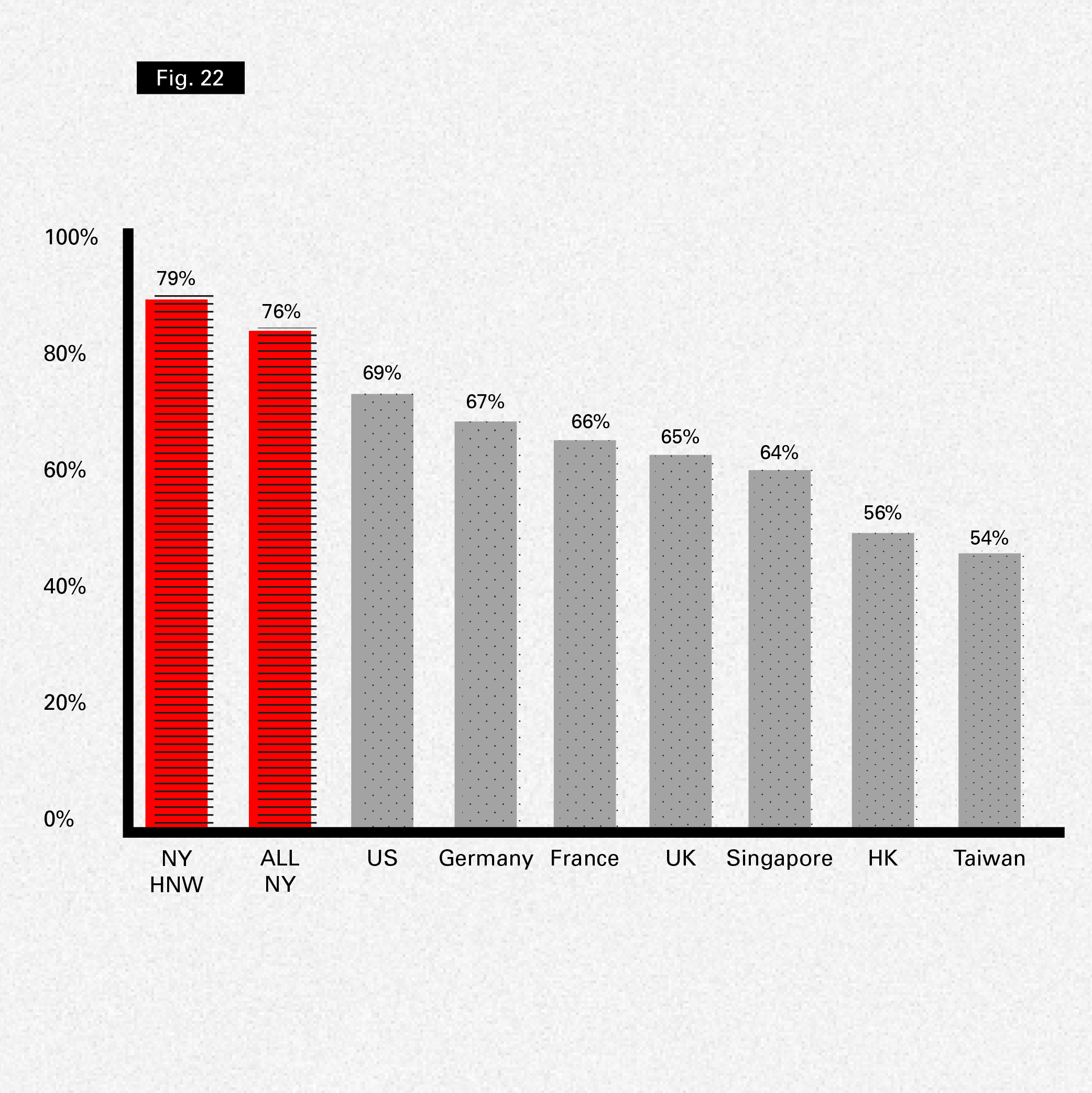

New York collectors are deeply embedded in the gallery sector, which is by far their most commonly used method for purchasing art. The use of galleries by New York collectors was high not only in comparison to other sales channels, but also in comparison to their collecting counterparts in other countries. Figure 22 shows that the share of New York collectors using galleries often or always was considerably higher than previous surveys of HNW collectors, across all of the other regions surveyed, including the US as a whole (at 69% versus 79% for HNW New York collectors).

Figure 22. Frequency of Use of Dealers and Galleries (Share of New York Collectors Using Channel Often/ Always)

© Arts Economics (2020)

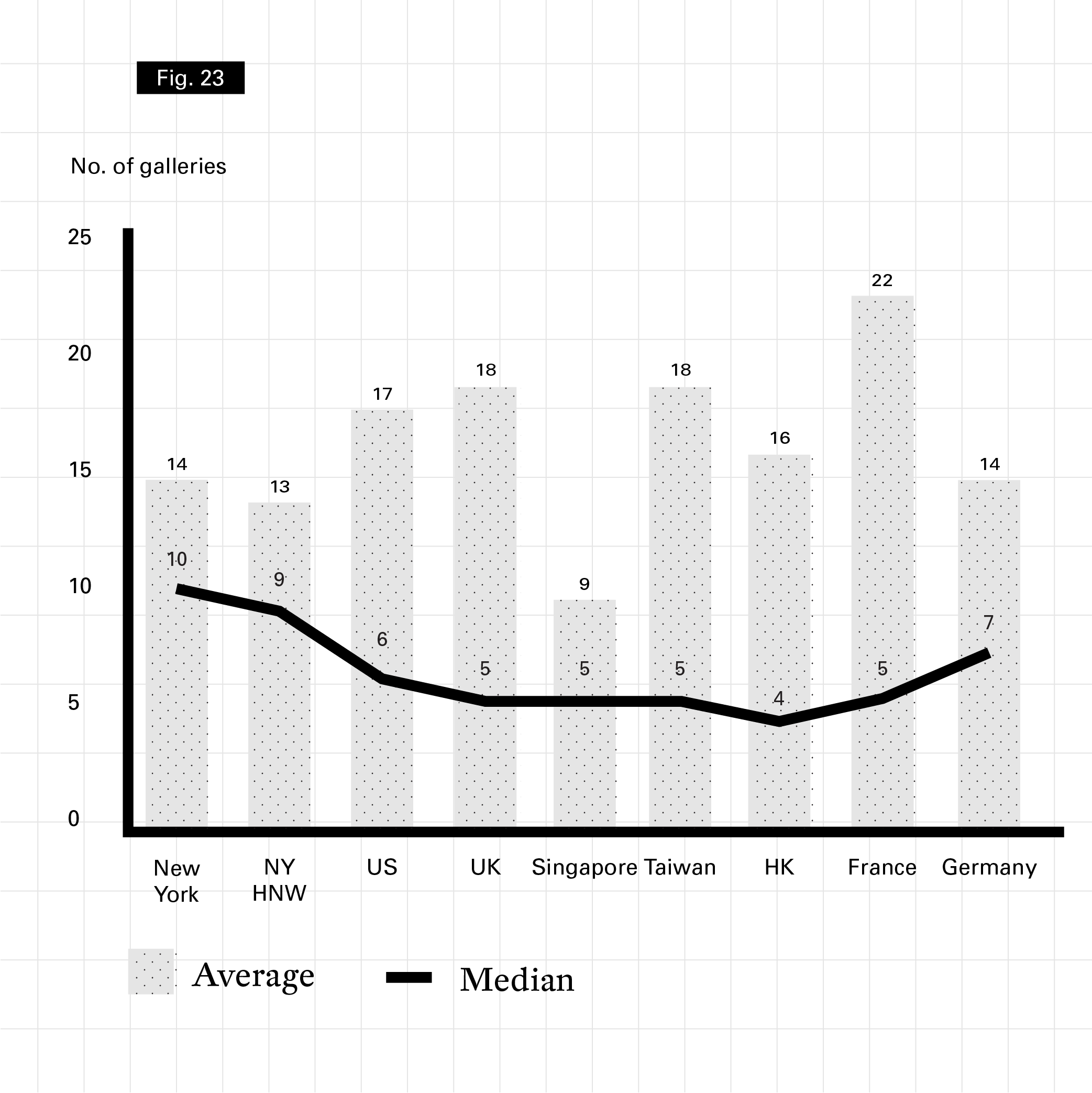

During the last two years, New York collectors reported that they had purchased art from 14 different galleries on average, with a median of nine galleries. Nearly all of the respondents (92%) had worked with New York-based galleries, but they also bought from galleries in the US and overseas. Based on the median number of galleries New York collectors had purchased from, the breakdown was:

45%

New York galleries

22%

galleries from

elsewhere in the US

33%

galleries from

outside of the US

A small number of collectors purchased from a very large number of galleries, with a maximum number of 175 reported in this sample over the two-year period. As in other samples, this small share of collectors can skew averages higher for the sample as a whole, making the median a more representative measure of what most or typical collectors do. (The median is the number of galleries splitting the largest 50% and the lowest 50% or the middle value in the distribution from highest to lowest).

It is interesting to note that although New York collectors work with a lower number of galleries on average than some of their global counterparts, considering the median (which removes the influence of these small number of high outlier values) the number of galleries used by New Yorkers is considerably higher and up to double most other national markets surveyed.

Figure 23. Median and Average Number of Galleries New York Collectors Purchased from in Last Two Years

© Arts Economics (2020)

Millennial collectors tended to have worked with the fewest galleries overall, with a median of six (with around half from New York). Boomers worked with the most, with a median of 11 galleries, but with the lowest relative share from New York, at 40% of their total. Gen X collectors worked with nine galleries (four in New York) and those from the Silent generation with 10, half of which were based in New York.

Wealthier collectors also tended to work with more galleries: HNW collectors from New York had purchased from nine galleries (four in New York) versus six for those with wealth less than $1 million. Those with wealth in excess of $10 million had an even higher median of 13 galleries (with six in New York).

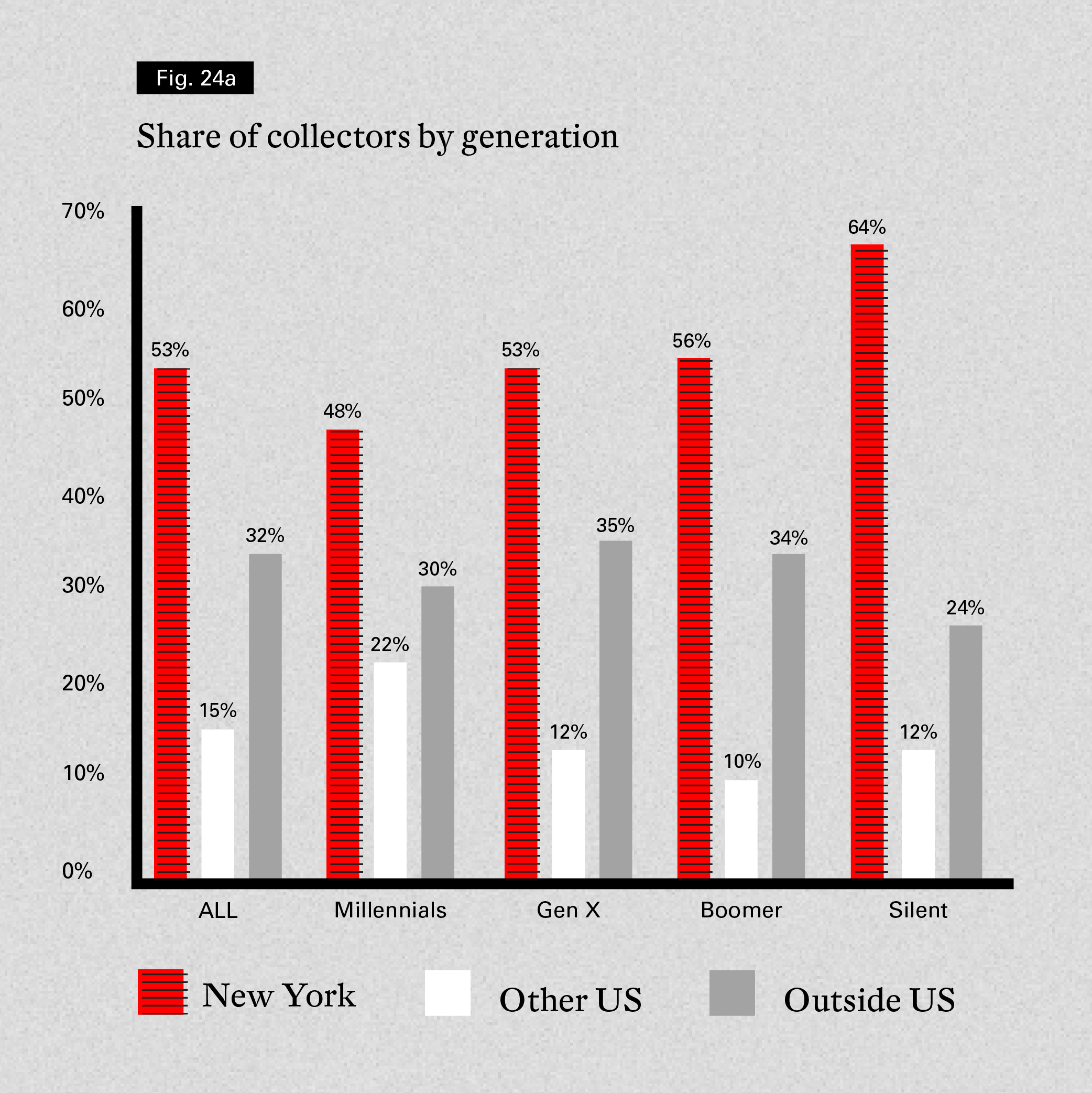

Collectors’ preference for working with New York galleries tended to rise slightly with the age of the collector. Just over half (53%) of the entire sample preferred working with New York galleries, while around one third preferred international galleries outside of the US, and just 15% opted for those within the US but outside New York. For millennial collectors, 48% reported a preference for New York-based galleries, while this was majority for older collectors, including 64% of those from the Silent generation.

Preferences for New York galleries also rose consistently with levels of wealth up to $50 million. At the very highest ultra-HNW level of $50 million plus, preferences shifted to galleries outside the US. This may in part be due to better access, or the fact that ultra-HNW collectors were also more likely to have multiple homes, including those outside the US, which may have influenced their ability to establish stronger relationships with overseas galleries.

Figure 24. New York Collectors’ Preferences for Purchasing by Gallery Location

© Arts Economics (2020)

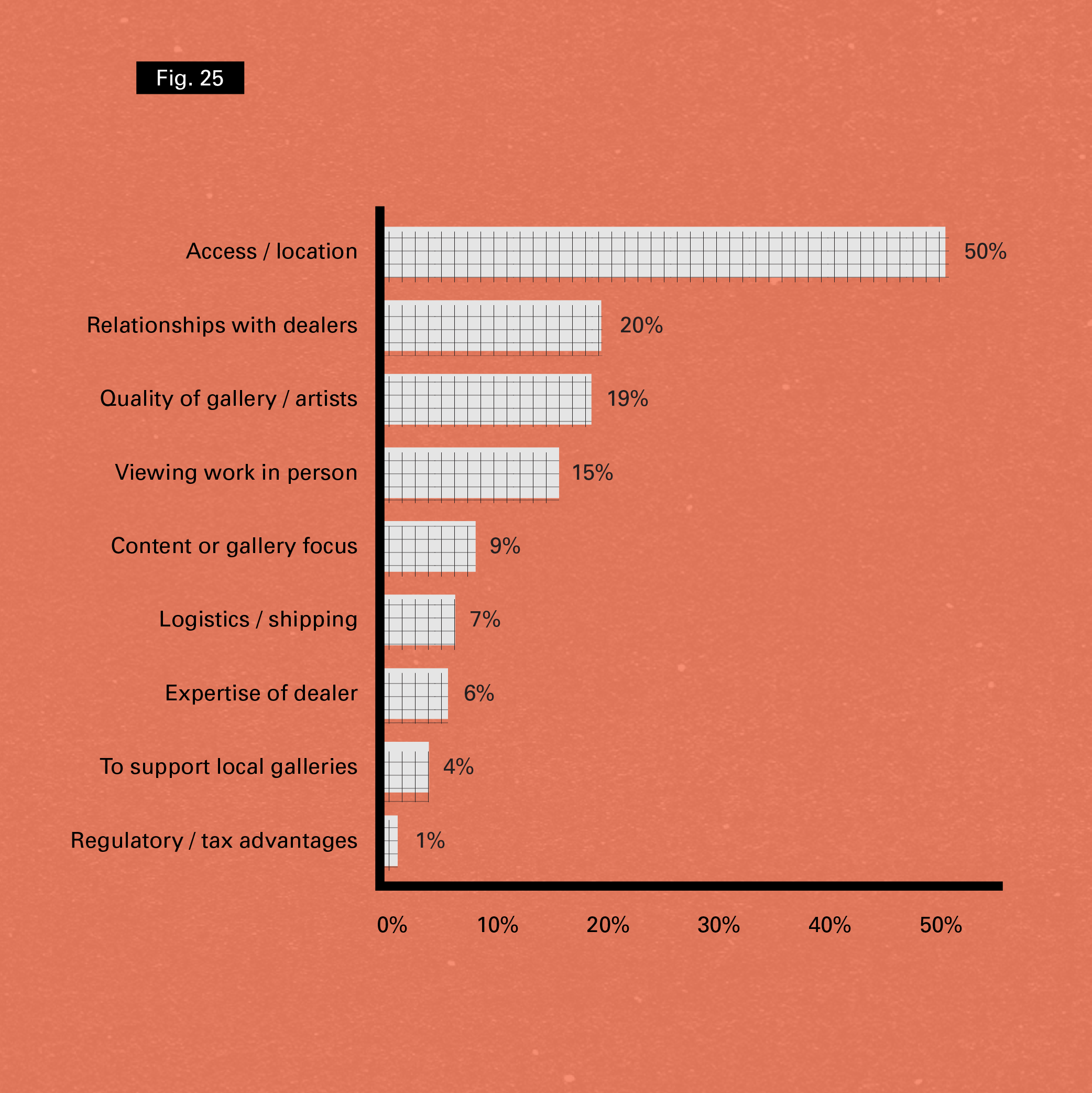

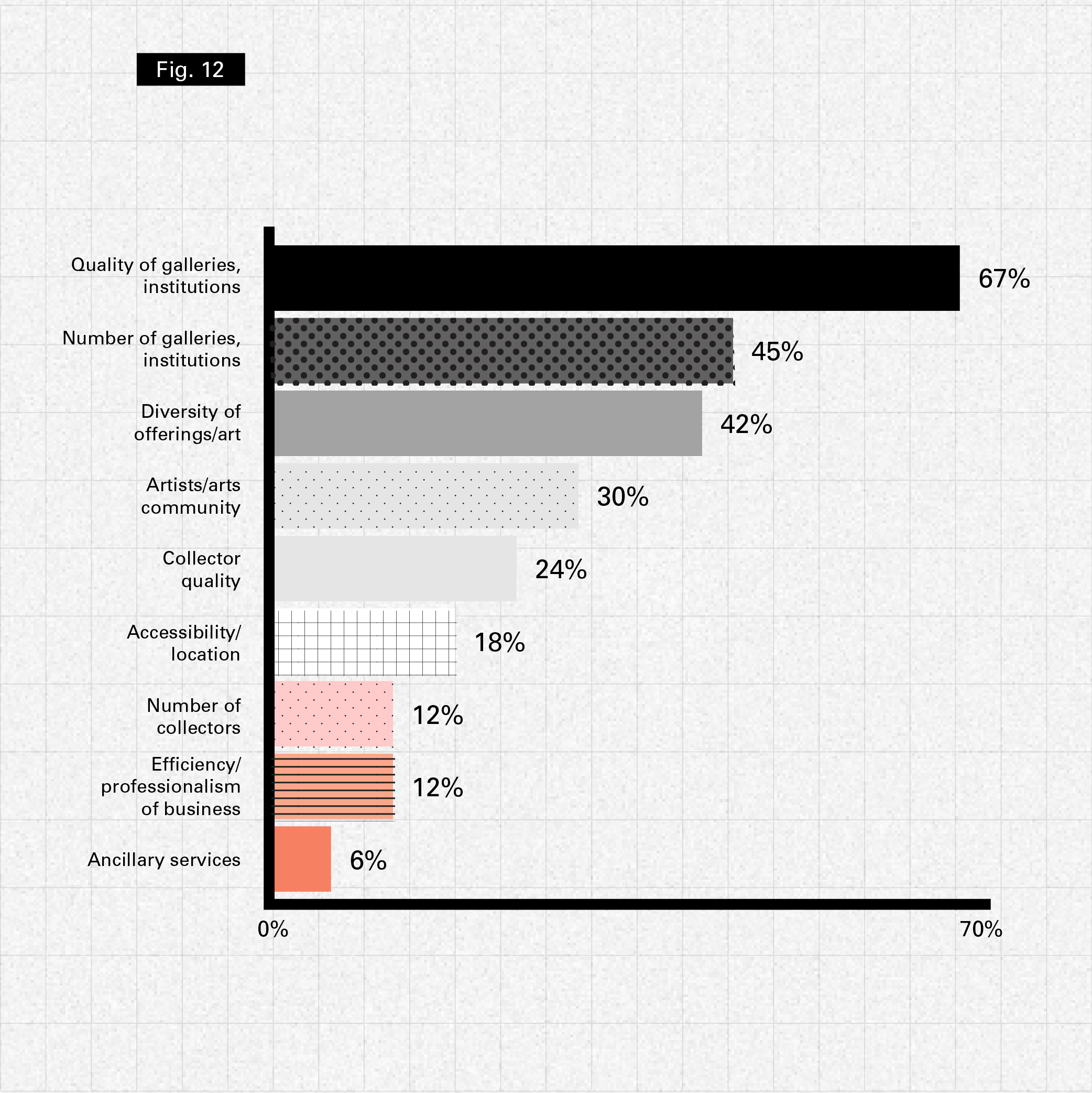

When asked why they preferred New York galleries, collectors had a variety of reasons. The most common responses centered on the ease of access and convenience of the gallery to where they lived, making it easier to attend exhibitions and visit more regularly, under normal circumstances. Even for those collectors who did not spend all of their time in New York, some commented on the benefits of having such a high concentration and range of high-quality galleries during their time there:

“...I like the geographic concentration of galleries in New York - when I am there I can see twice as many even in a short time than in any other city in the world...”

Others commented on the relationships and trust they had established with dealers in New York, as well as the superior quality of their galleries and the artists that they showed, citing them as having the best, most important and in some cases most diverse works on offer. Several respondents also mentioned the professionalism and knowledge level of individual dealers in New York, citing their trustworthiness, reliability and superior knowledge and access.

“...Besides location, dealers here have a great selection of work. Seeing, buying and taking possession of the work is relatively frictionless and they are easy to stay in contact with...”

Several commented on the ease of logistics, shipping and other practical reasons for their preferences for New York galleries, while others were more motivated by supporting local businesses and artists, particularly emerging galleries and artists.

“...I have a strong belief in supporting New York galleries and try to only collect artists residing in New York City...”

“...New York City is the epicenter of the art world and, as collectors of emerging artists, it is key that their work be seen and noticed by the art world in general. New York fairs and galleries provide that exposure...”

Figure 25. Motivations for Preferring New York Galleries (Respondents who Preferred New York Galleries)

© Arts Economics (2020)

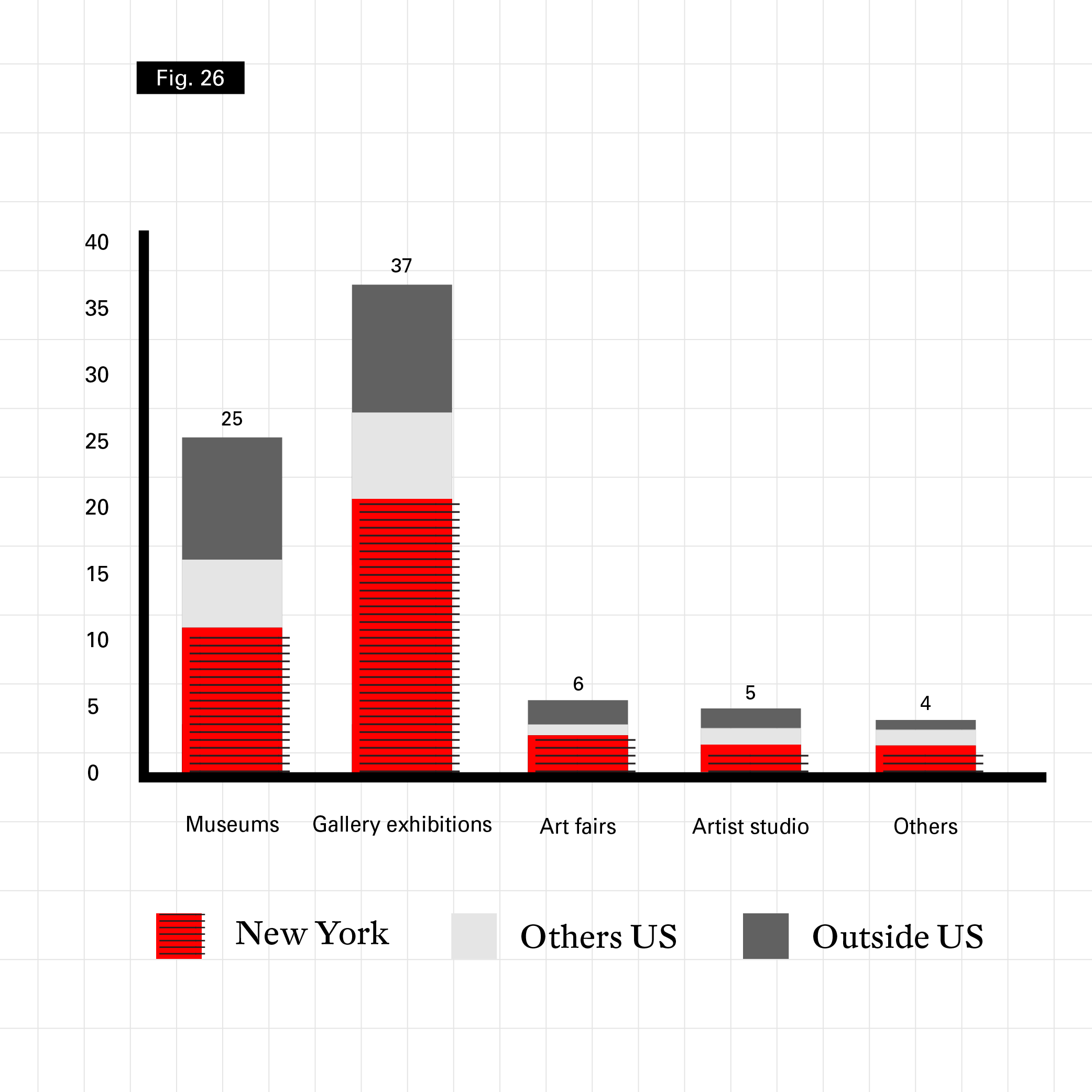

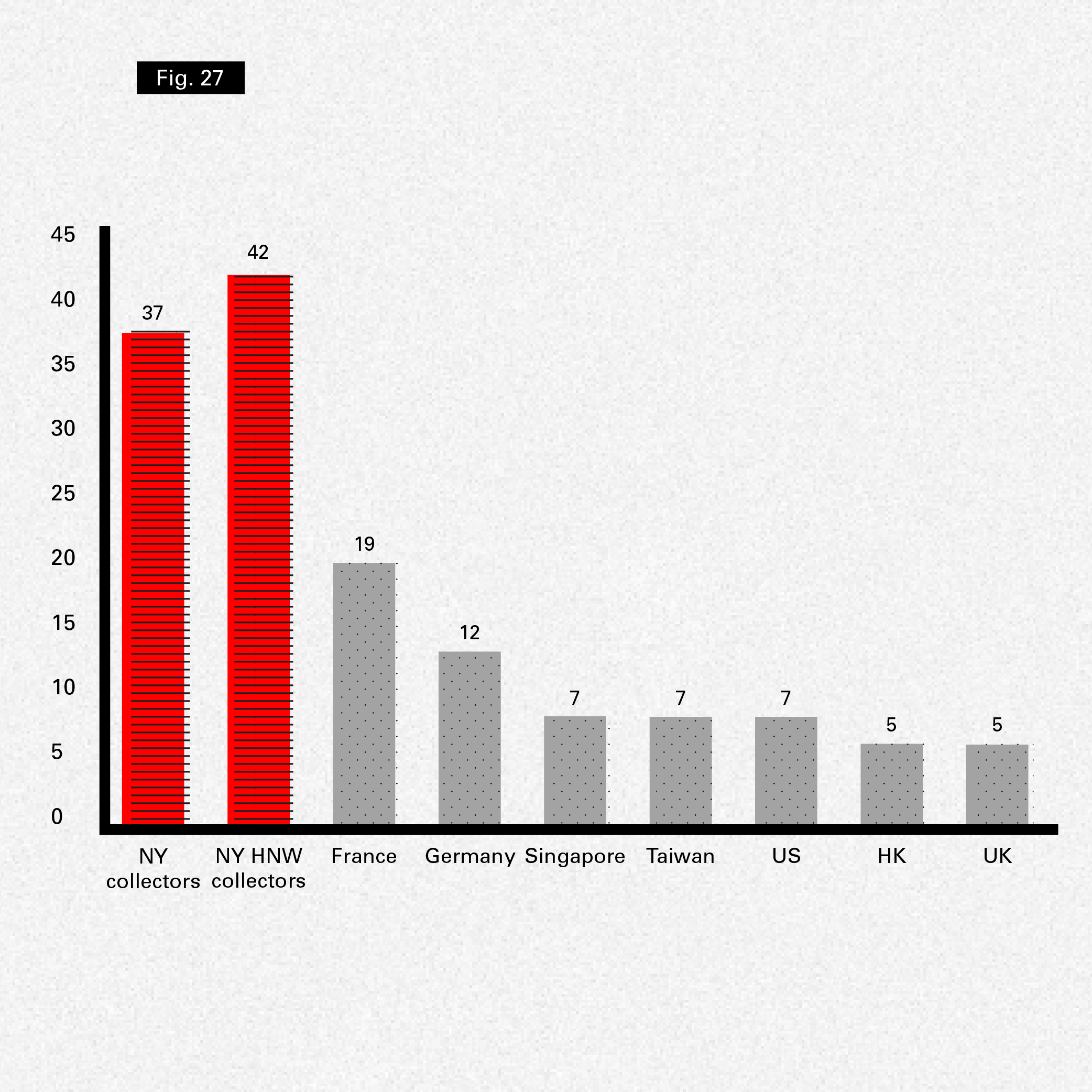

Apart from purchasing from galleries, New York collectors were also highly active in supporting gallery exhibitions. Residing in the epicenter of the art market, with a wide and diverse range of events on their doorstep gives collectors in New York unparalleled exposure to the art world. This was reflected in their participation in events, with collectors from New York having attended a significantly high average of 77 art-related exhibition events in 201921. Previous research of HNW collectors showed an equally frenetic cycle of event going up to 2020, with averages ranging from around 25 exhibitions attended by collectors in the UK and Hong Kong in 2019, 62 by those from Germany and 77 by French collectors. However, these collectors showed a much higher engagement in the non-commercial art sector with museum exhibitions dominating, while New York collectors were most active in the gallery segment, which accounted for close to half of their exhibition attendance, regardless of their age or wealth levels.

Figure 26. Attendance at Exhibitions / Events by New York Collectors in 2019 (By Type of Exhibition and Location)

© Arts Economics (2020)

On average, New York collectors attended 37 gallery exhibitions in 2019, which was almost double the attendance reported by other HNW collectors from different regions in previous research for 2019. The majority of these were in New York (21), with six in other parts of the US and ten outside the US. Millennial collectors had a slightly lower average attendance at 33 exhibitions relative to their older counterparts, who averaged 40 or more. Attendance also increased with the wealth of the collector, with those with wealth in excess of $10 million attending a high of 44 events on average.

Figure 27. Attendance at Gallery Exhibitions in 2019 (By Collector Region)

© Arts Economics (2020)

New York collectors actively attended art fairs, and most (96%) had also purchased art at fairs, with 43% using them always or often to do so. The use of art fairs was highest among boomer collectors (46% of them using them always or often to purchase art), versus around one third or more for other collectors. Their regular use also increased with levels of wealth, from one third of collectors with wealth less than $1 million to 44% of collectors with wealth in excess of $10 million.

New York collectors attended six art fairs on average in 2019, which was on par with averages in other regions, and also consistent across generations and wealth levels within the New York sample. Three of these were fairs in New York, one in another part of the US and two overseas. When they were asked the reasons for attending an art fair over a gallery exhibition, the three most common reasons given were:

The least important aspects of attending art fairs were the dinners and other social events associated with a fair, as well as attending talks and lecture programs. However, these were both much more important for younger, millennial collectors in New York than their older counterparts, who, with less experience in collecting in some cases, may have been more interested in gaining knowledge on the market and availing of potential networking opportunities.

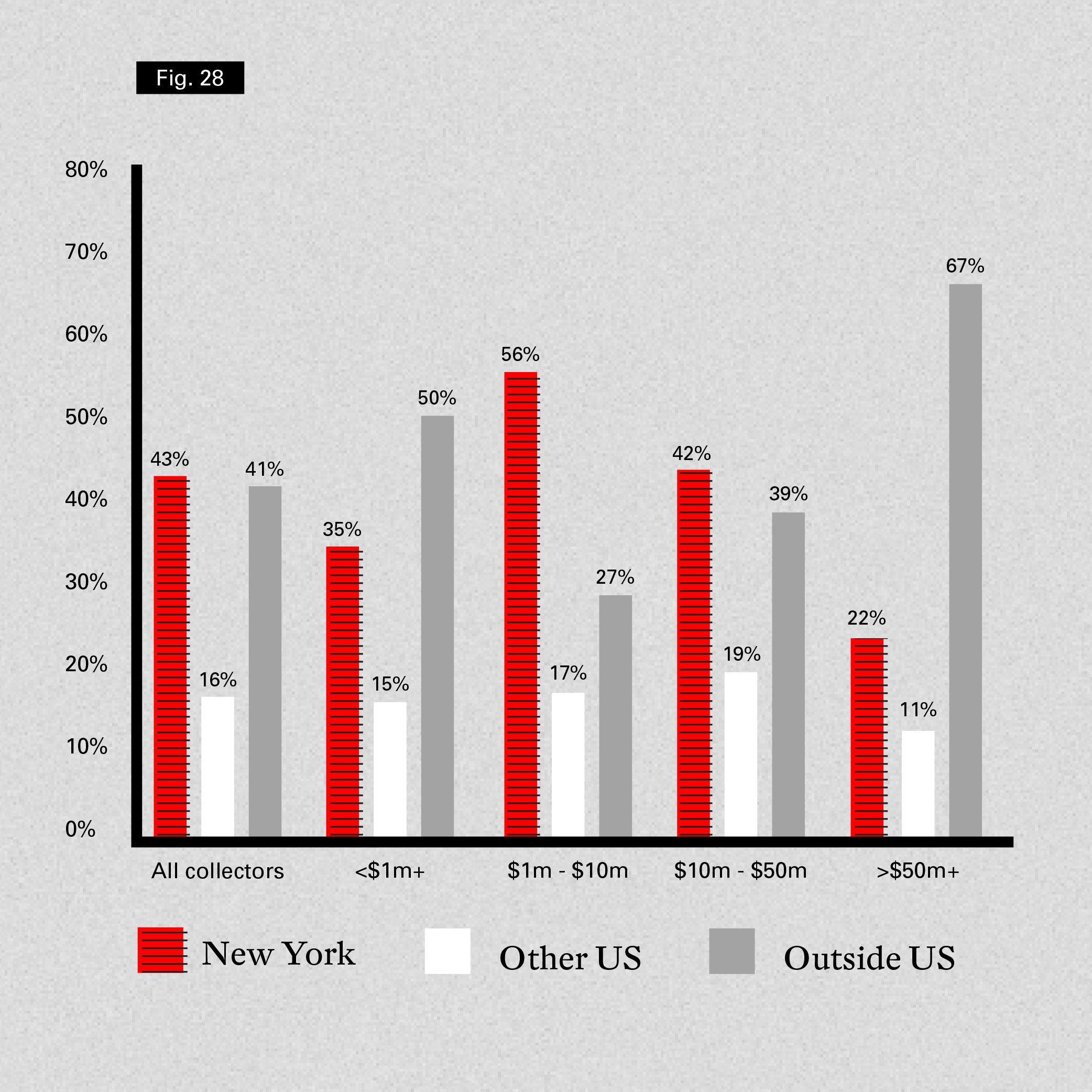

There were some differences in collectors’ preferences for local fairs versus those outside New York. Across all collectors, 43% preferred to attend and purchase from New York fairs, followed by those outside of the US (41%). Older collectors had a slightly higher preference for local fairs (with 47% of boomers and 63% of those from the Silent generation preferring events in New York), while Gen X collectors had the highest share of preferences for overseas fairs (47%). Preferences for local fairs rose by wealth level up to $10 million, but at the highest level of $50 million plus, as was the case with their choice of galleries, a higher share of ultra-HNW collectors opted for overseas events (67%).

Figure 28. Share of New York Collectors by Preference for Location of Art Fairs

© Arts Economics (2020)

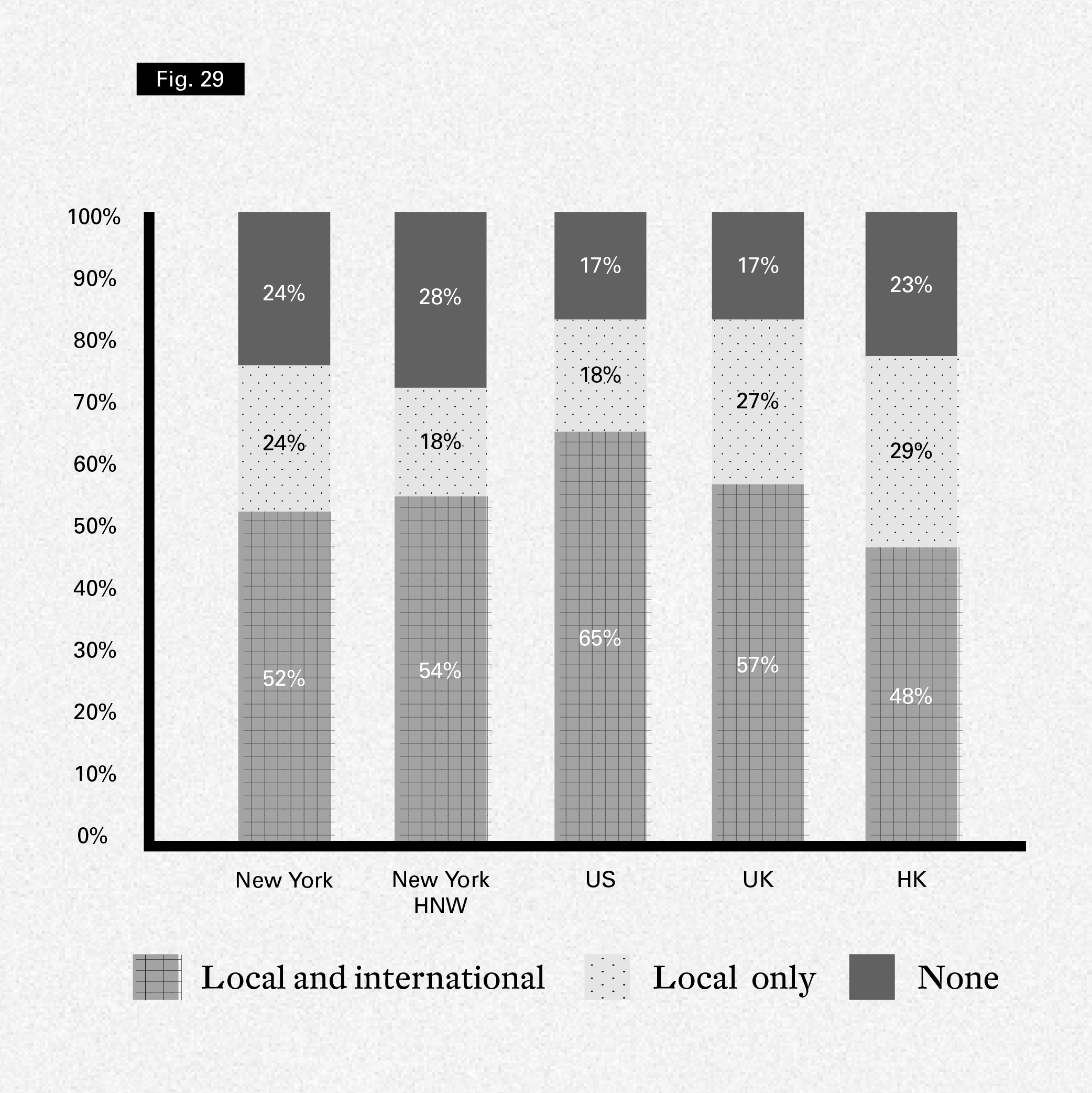

Although New York collectors were highly active at events in 2019, the COVID-19 pandemic has significantly reduced the ability and willingness of many collectors to attend exhibitions. Research on HNW collectors in the US, UK and Hong Kong carried out by Arts Economics and UBS in 2020 showed that for the full year in 2020, collectors expected they would reduce their attendance at events by about 40%22. Despite the ongoing limitations and restrictions on travel and attendance at events during the pandemic, most of these HNW collectors (81%) were still actively planning to go to exhibitions, art fairs and events in the next 12 months, and a majority (57%) hope to attend these events both locally and overseas. US collectors were the most interested in international events (65% planned to attend these alongside local ones), while collectors in Hong Kong were more cautious about going overseas (only 48% planned to attend international events in the next year).

To assess the effects of the pandemic on their willingness to attend events, New York collectors were also asked about their plans over the next 12 months. As with their global counterparts, the majority (52% of collectors and 54% of HNW collectors) were planning to attend events, art fairs and exhibitions over the next 12 months both locally and overseas. However, New York collectors appeared to be slightly more affected by the fallout from the pandemic, and a larger share of 24% not planning to attend any events. This also parallels the general sentiment of US consumers. UBS Evidence Lab Consumer Surveys in 2020 showed that willingness to travel declined significantly from June to the start of August, with the majority of US travelers not willing to travel or go on vacation until 202123. Of the 24% of collectors in New York that would only attend local or national events, around half said they would be sticking to those in New York only. Overall therefore, 76% of the collectors surveyed were willing to attend events, exhibitions and fairs in New York over the next 12 months.

The regional HNW collector research in 2020 indicated that millennial collectors in the US, UK and Hong Kong were considerably more likely to travel than older collectors, with 70% willing to travel internationally versus less than half that share of boomers. For New York collectors, this was not the case: millennial collectors only had a slightly larger majority willing to travel locally or internationally (57%) than boomers (55%). Collectors from the Silent generation showed the least enthusiasm at 37%, although 42% were still willing to attend events within the US.

Previous studies also showed that travel and attendance plans rose in proportion to wealth, with the wealthiest collectors planning to attend both more events and more international events. This was also not the case in New York, where wealthier segments of collectors were less likely to attend exhibitions and related events over the next 12 months (32% of those with wealth over $10 million versus 23% for those under $1 million).

Figure 29. Planned Attendance at Local and International Events in Next 12 Months

© Arts Economics (2020)

Although there may be a variety of factors that influence collectors’ travel plans, restrictions and reductions in international travel due to the COVID-19 pandemic were clearly a key concern for collectors in New York: 69% reported being very or extremely concerned about their impact. This was a much more pressing concern for collectors than the sustainability and the carbon footprint of the art market and its related activities: although 72% of respondents felt these issues were important, only 35% were very or extremely concerned about this impact when surveyed in 2020. Further, only 26% HNW collectors in New York rated sustainability as very or extremely concerning. HNW collectors in other regions asked to rank concerns in a similar manner in 2020 showed a higher level of concern: 63% in the US as a whole, 57% in the UK and 47% in Hong Kong. In these markets, as in New York, the very present concerns over the impact of COVID-19 have outweighed some of these critical but longer-term issues in the market in 2020.

Reduced access to museum exhibitions was also a key concern for New York collectors, the third highest ranking concern overall next to the closure of galleries due to COVID-19 and a lack of sufficient support and funding for the arts. 69% of the collectors reported being extremely or very concerned about lack of museum access. Although most collectors (84%) were at least somewhat concerned by the reduced opportunities to network and socialize at fairs, galleries, art-related events due to COVID-19, just over half (54%) of respondents reported as being very or extremely concerned about this in 2020.

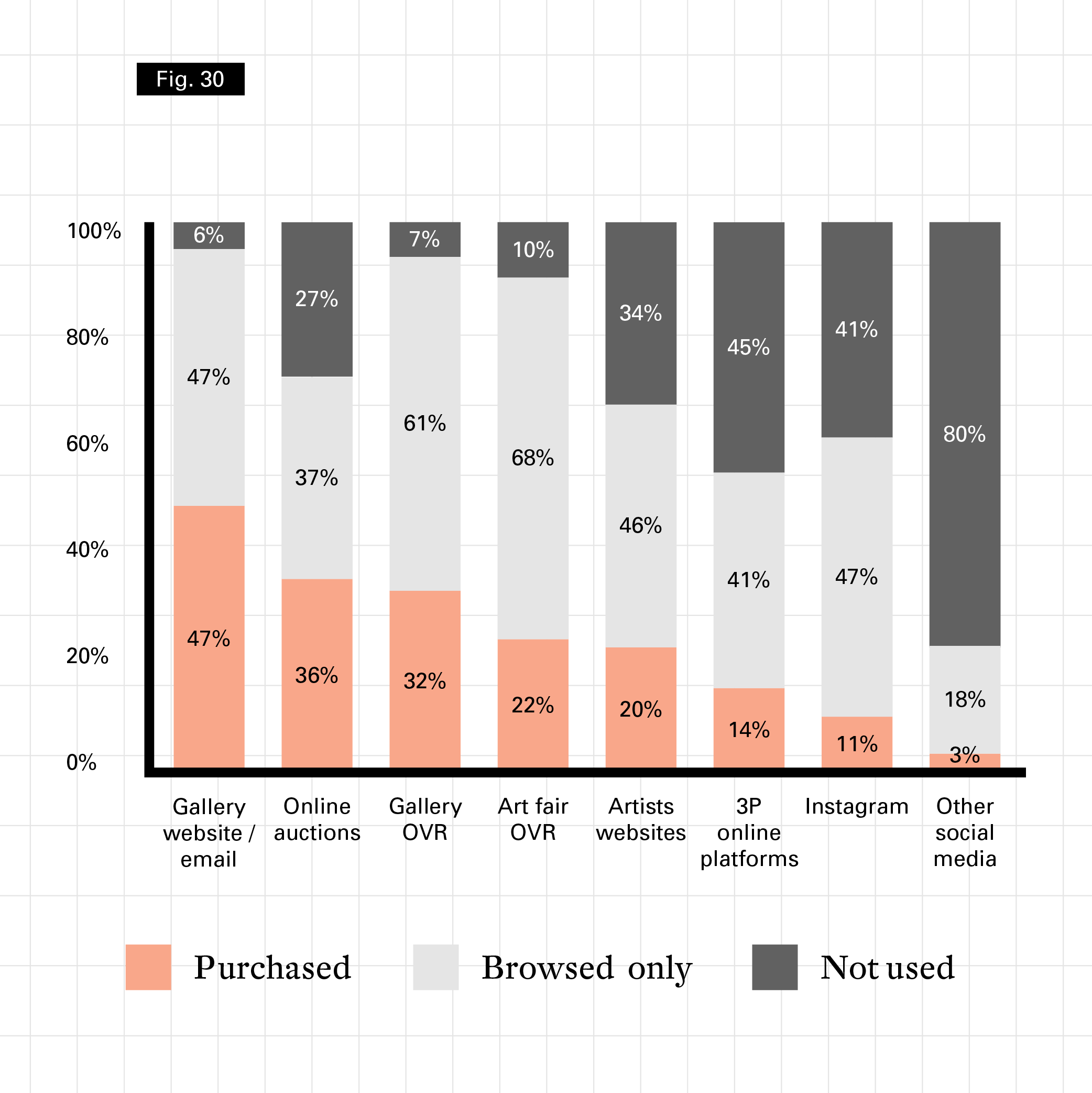

During 2020, the closure of many New York galleries and events meant that online channels were often the only way galleries, auction houses, fairs and artists could access some collectors. There was a range of online offerings that allowed collectors to still purchase works of art while physical premises were closed, and most of the collectors surveyed actively used online platforms to both browse and gain information as well as to complete purchases.

Figure 21 showed that only 10% of New York collectors used online platforms to buy art always or often, and just over one quarter of respondents had never purchased from an online platform. Social media platforms were much less used: only 2% of collectors used Instagram often or always and 73% of those surveyed had never used Instagram to buy art directly. However, collectors were active on the websites and platforms of galleries and fairs.

The most commonly used online channel for purchasing art in the last 12 months was through galleries’ websites or via email (47%), while 32% of New York collectors had used an online viewing room (OVR) from a gallery. Most collectors (90%) had used art fair OVRs to browse works of art for sale online, although only 22% had used them to make a purchase. This was slightly lower than the average found in 2020 across HNW collectors elsewhere, ranging from 36% in Hong Kong to 49% in the US as a whole. The average rose considerably for New York collectors as wealth increased, with 36% of those collectors with wealth in excess of $10 million having purchased from a fair OVR, and 44% for those with wealth greater than $50 million.

Online auctions, which have been accessible to art collectors for a considerable amount of time with the auction sector leading galleries in terms of their pivot to online over the last decade, were used by 36% of collectors to purchase works (on par with averages in other regions).

Instagram was by far the most widely used social media channel, although only 11% of collectors in New York had used it to buy art in the 12-month period. Millennial collectors were the most likely to buy directly from artists’ websites, with 57% of respondents from this segment having done so in the last 12 months, versus a small minority of older collectors who stuck largely to online offerings from galleries, auctions and fairs.

Figure 30. Use of Online Platforms in the Last 12 Months

© Arts Economics (2020)

During 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic undoubtedly introduced significant disruption to collectors’ normal patterns of interaction with the market in New York, changing their access and interactions with galleries and auction houses, as well as their ability to attend exhibitions, art fairs and other events within and out of the city. Many collectors have only been able to view and transact online, which for most is not their preferred or most frequently used method of engagement with the art market under normal circumstances. Galleries noted in previous research in 2019 that in uncertain political and economic contexts, it had been difficult at times to keep collectors focused on buying art. This issue increased dramatically during 2020 as many collectors focused primarily on safety, health, social, and financial concerns. However, unlike some other recessions, there has also been a high level of awareness and strong drive by some collectors of the need to support the arts, and help ensure the survival of galleries, artists and museums during the crisis.

For a majority of New York collectors, these ongoing uncertainties fed into pessimism and a lack of clarity regarding the outlook for the art market globally and in New York over the next year. Only 21% of respondents were optimistic about the global art market’s performance over the next 12 months, with a large share unsure of the outlook for the local or global art markets. This in part indicates the continuing lack of clarity over how the course of the pandemic might progress and the travel, lifestyle and other adjustments that may still need to be made. It is notable, however, that the outlook collectors have for the art market was roughly on par with their outlook for global equity markets over the short-term, and reflects a generally less optimistic view, rather than one specifically for the art market.

Over the longer-term, confidence in the global and New York art markets advanced, mirroring more general increases in optimism for the future (with the global equities outlook following a similar trajectory). However, optimism regarding the global art market was slightly higher than the New York art market, with most collectors (81%) optimistic about global sales in the next decade, including 37% that describe themselves as very optimistic.

It is also interesting to note that, comparing the outlook of New York collectors to their HNW counterparts in the US generally or in other major art markets, New Yorkers were more pessimistic about the global art market for the next 12 months (48% pessimistic versus 22% in the US, 21% in the UK and 34% in Hong Kong). However, they have a considerably more positive outlook about the longer-term, with a higher share of optimism and a lower share of pessimism (only 1% of New Yorkers were pessimistic over a ten-year period versus 12% to 14% in the other regions).

While other surveys have shown more optimism among younger collectors, this research revealed that there was, in fact, higher optimism and less pessimism for boomer and Silent generation collectors in New York, over all periods regarding the global art market, but particularly the New York market. Although the reasons for this may be varied, some of these collectors may have more experience of the resilience that the market has exhibited over time.

Table 1. New York Collector Optimism: Global and New York Art Market and Global Equities

© Arts Economics (2020)

While there was a relatively high level of optimism about the medium to long-term future of the art market, some of the most pressing current concerns for collectors center on the ability of the market to recover from the current crisis in the short-term. New York collectors, who work closely with galleries, showed a very high level of engagement with exhibitions and events in the city. The highest rated concern of New York collectors about the market in 2020 was the potential closure of galleries due to COVID-19 (with 96% of collectors rating this important and 79% very or extremely so). Second highest ranking was a lack of sufficient support and funding for the arts, while rising rents for artists and galleries in New York was also a key concern, and the second highest for millennial collectors.

Some collectors commented on the dangers the city faced, and particularly the future for smaller and emerging galleries and artists:

“...Rising retail rents in New York City were already a big problem for middle to emerging art galleries, as well as retail spaces before Covid-19. It has been getting worse since about 2018, and I have found the energy level of the city suffering as well. The city is not maintaining its infrastructure...”

“...I am concerned for dealers of starter galleries - between Covid restrictions, high rents in NYC and crime - I think they have a hard road ahead. ...”

“...I have no doubt the market for brand name artists on the secondary market will continue to rise. I am not sure what will happen in the primary market, and especially about the fate of New York as a center for artists and the eco-system they spawn to live, work, and productively influence one another in...”

Others, however, were more optimistic about its potential to withstand the current crises better than other parts of the global art market:

“...Of all places New York art market will do great, and will recover first - it will be followed by global art markets. I am very positive...”

“...I expect the art world will get back to its normal self within the next 16 months. Some galleries will fold but others will replace them. With those closing we will lose some artists but they too will be replaced by others. Some that lose their gallery will find another to represent them. More showing and buying will be done on internet but I will never feel very confident buying something I have not seen in the flesh...with possible exceptions and against my better judgment...”

Art advisors have become an integral part of the art market over the last 20 years, playing a central role in the interactions between many galleries, collectors and artists in New York. As well as gaining in number, art advisors have also expanded in terms of the services they provide, ranging from the more traditional artistic advice (such as what paintings to buy and how to successfully access them) to offering specialized tax, legal and financial advice and investment services. Apart from the knowledge and access they offer, collectors have also noted the benefits of these advisors as being independent from auction houses and dealers, and hence providing more impartial and objective advice on quality and value. Some noted that in other investment markets, buyers would not approach any major investment or purchase without a team of advisors, so therefore see the growth of the role of art advisors as moving in tandem with the increased size of the market, as well as the spending budgets and price points of collectors.